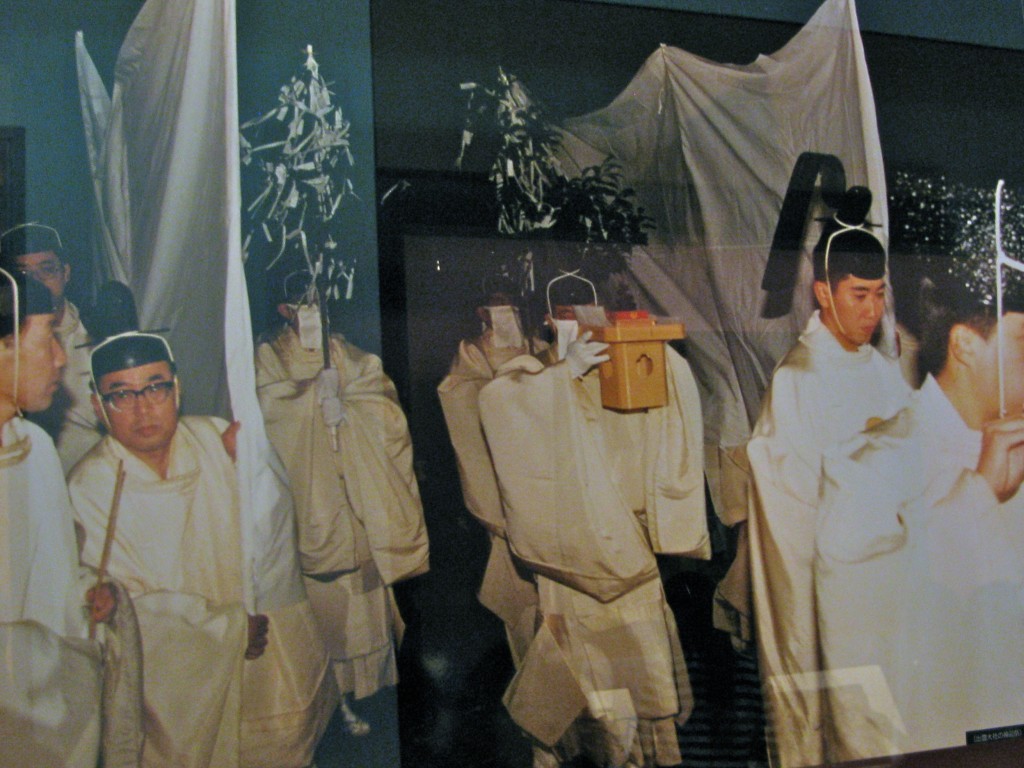

The kamiari festival on the beach at Izumo, where Japan's "yaoyorozu" kami (eight myriad kami) are welcomed ashore

Polytheism and pluralism

The new edition of Japanese Religions, a journal published by the NCC in Kyoto, carries an interesting article by Ugo Dessi, lecturer at Leipzig University. In his paper Dessi looks at how pluralism has been used by Japanese intellectuals in recent years to promote a nationalist viewpoint. It’s a curious paradox, since one might presume pluralism to lead to tolerance and open-mindedness, but the thrust of the right-wing argument is that it makes Japan special.

In the first section of his paper Dessi considers the thinking of Shinto intellectuals, such as Yoro Takeshi and Umehara Takeshi. Their ideas rest on the opposition of polytheism and pluralism on the one hand, and Christianity and monotheism on the other. The latter is portrayed in 1960s terms as exclusivist, dogmatic, patriarchal, aggressive and destructive of the environment. It is also depicted as inherently Western.

By contrast the Asian way is identified with polytheism, which is able to embrace multiple and mutually contradictory truths. “In its long history Shinto (we may well say in this case, the Japanese people) has accepted Buddhism, Confucianism, and yin-yang thought and has intermingled with them. This is because at the root of this process lies the acceptance of a plurality of truths,” says a Jinja Honcho pamphlet (2009).

Shrines in Japan often worship several kami at once

A special relation to nature

Some writers have gone further than simply championing the merits of polytheism to suggest that Japan is special. “It is interesting,” writes Ugo Dessi, “to notice that in institutional Shinto the critique of monotheism is also meaningfully connected to the invented tradition of Shinto as a ‘religion of the forest.’ In a self-presentation by the powerful Shinto Kokusai Gakkai (ISF), started in 1994 to promote the study and understanding of Shinto worldwide, the critique takes its cue from the distinction between ‘shallow ecology’ and ‘deep ecology’.”

Dessi’s article goes on to consider other branches of Japanese religion, and comes to the conclusion that rather than leading to openness and inclusiveness, the current vogue for championing polytheism might actually be fuelling the right-wing discourse of nihonjinron (debate about what it is to be Japanese).

Personally, I would have thought that polytheism offers an important means of coming together, and that far from reinforcing divisions, it contains the potential for tolerance based on plurality. In my sabbatical year I will be researching polytheism and paganism in the British Isles, while considering how they parallel developments in Shinto. In this way I hope to build a bridge between East and West, and gain a greater understanding of what the traditions can offer each other.

******************************************************************************************************************************************

Information is drawn from ‘Japanese Religions, Inclusivism, and the Global Context’ by Ugo Dessi in Japanese Religions Vol. 36 Nos. 1 and 2 (Spring and Fall, 2011), p.83-99.

The circle of life: passing through the 'chinowa' at a shrine this week for midyear purificaiton

Leave a Reply