Shinto torii leads to Buddhist gate in the Shingon temple-shrine complex on Shiraishi Island

This post is part of a series exploring the pagan pasts of Britain and Japan. One of the salient differences was the attitude of the continental axial religions (Buddhism and Christianity) to the earlier religious practice. In Japan the fusion of Buddhism and kami worship is known as syncretism, which emerged as the country’s mainstream form of spirituality. (For earlier parts of the series, click here or here.)

***********************************************************************************************************************

The contrast with Britain

Snake water basin at Miwa Shrine in Nara Prefecture

Christianity was an exclusive monotheist religion, which held that there was only one truth. As a result Catholicism portrayed indigenous religions as evil and sought to suppress their practice. The conscious rejection of paganism is reflected in the Bible in the demonisation of the snake, or serpent. Since ancient times the creature had been a potent symbol of rebirth and revitilisation, because of the ability to slough off its skin, and it was worshipped in Japan as can still be seen at Miwa Shrine near Nara. In Christianity, however, it was made to represent the very essence of evil by tempting Eve in the book of Genesis to eat from the forbidden apple.

Yet at the same time Christianity sought to exploit the popularity of pagan customs by such strategies as building churches on sites associated with pagan spirituality. Glastonbury Tor is the most famous example, for the small hill had been revered as sacred since ancient times (one theory holds that it was the site of an esoteric maze leading to a higher plane), but in medieval times a church was built at the top of the hill and dedicated to the archangel St Michael.

The tower of St Michael's Church atop the pagan mount of Glastonbury Tor

Another example of the Christianisation of pagan sites is the conversion of holy springs, which were revered by ancients as outflows from Mother Earth. At Oxford there is a ‘treacle well’ in the village of Binsey, mentioned in Alice in Wonderland, which was thought in pagan times to have healing qualities but which in Catholic times was re-imagined as the site of a miracle by the city’s patron saint, Princess Frideswide. According to legend, she used water from the spring in an act of mercy to bathe the eyes of her assailant, who had been struck blind from on high while trying to rape her. (1)

Accommodation

By contrast with Christianity, Buddhism was more accommodating. From its very inception in India, the religion had embraced Hindu deities as unenlightened guardians of its doctrine. As Buddhism spread across Asia it followed a policy of accepting local gods in similar manner, and the integration of Bon animism into Tibetan Buddhism is an example. By the time the religion had travelled across South-east Asia and China, there was already a proven path of incorporating local belief. Japan was to prove no exception, and kami were accepted as tutelary spirits of place which played an important part in the communal life of the populace, particularly as regards rice cultivation. Buddhism on the other hand was concerned with metaphysical matters, such as liberation from the cycle of existence. As a result ‘this-worldly’ Shinto and ‘other-worldly’ Buddhism came to complement each other, and the two religions settled into a symbiotic existence which lasted right up to the Meiji Restoration of 1868.

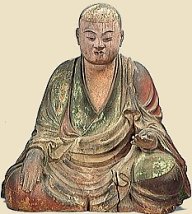

Sogyo Hachiman (courtesy onmarkproductions.com)

The syncretic arrangement was already evident in 752 when the Great Buddha of Todai-ji was presented to the nation as being under the protection of the kami Hachiman, transported from Usa in Kyushu after an oracle there by a miko shamaness declared it was the wish of the deity. (It’s said to be the first use of a mikoshi.) The kami governed the spirit of place; the Big Buddha was in charge of cosmic matters. The respective size of the buildings reflected the significance of their deities in the greater scheme of things.

Kami-Buddha equivalence

Before long a theory known as honji suijaku (essence-trace) arose to formalise the arrangement between kami and Buddha. The term appears in documents for the first time in 825 in reference to the notion that while hotoke (Buddhas) are the true essence, kami represent their shadowy trace. In other words, there was a contrast between transcendent deities on the one hand and local avatars on the other.

Universal Buddhas were thus represented in Japan by particularist kami. Needless to say, this was a Buddhist theory in which kami were relegated to a supporting role. Indeed, they were ascribed a relatively low position in the Buddhist hierarchy, higher than humans but nonetheless in need of enlightenment. A notable example is Sogyo Hachiman, a kami portrayed in the guise of a Buddhist monk. Like his human counterparts, he was on the path to enlightenment.

In this way syncretism was given ideological justification which was unquestioned until the appearance of Yoshida Kanetomo (1435-1511), who tried to reverse the doctrine by asserting that kami were the true essence and the Buddhas their shadowy trace. Nonetheless, for over 1000 years Buddhist-led syncretism remained the mainstream in religious matters and the concept of something called ‘Shinto’ was virtually unknown. The worship of kami, together with all the attendant rites and festivals, was largely carried out under the Buddhist umbrella. Indeed the two traditions were so integrated that they were treated as a uniform whole. When the Tendai warrior-monks of Mt Hiei descended on Kyoto, they carried with them a mikoshi bearing the mountain kami Sanno, and when people were in extremity they called on all the kami and buddhas for help, regardless of the provenance of the deities.

Purification the Japanese way, mixing both Shinto and Buddhist elements with its lotus flower water basin

[1] For a full account of the Frideswide legend, see John Dougill Oxford in English Literature Uni. of Michigan, 1998, p. 13

Leave a Reply