This is part of an ongoing series comparing the Pagan religions of Britain and Japan. The previous post, Part 5, focussed on the fusion of Buddhism and kami worship that for more than 1000 years was the mainstream of Japanese religion.

**********************************************************************************************************

By the nineteenth century the situation in Britain and Japan had certain similarities, in that a dominant axial religion had incorporated traditional folk elements. There were of course significant differences in the extent, since Christianity had more or less erased Paganism, though Shinto too was more marginalised than is sometimes thought. Not only was Buddhism the official religion of Tokugawa Japan, but it was an important part of state control. Everybody had to be registered with a temple, including the small number of ‘Shinto priests’ (perhaps just 5% of those leading rites of kami worship).

Priest in formal costume (saifuku), courtesy Kokugakuin Encyclopedia. In Edo times, only about 5% of kami worship was carried out by 'Shinto priests'.

In Shinto and the State 1868-1988, Helen Hardacre characterises Shinto in the Edo era as ‘a mere appendage’ to Buddhism. There were localised cults with independent lineages, but there was no central authority. Moreover, there was no unified training of priests. The vast majority of kami worship was conducted by Buddhist monks, Shugendo practitioners, shamans, or village elders.[1] The rites were not considered part of something called Shinto, any more than giving Easter eggs in Britain was considered Pagan.

Most shrines in Edo times were under Buddhist control, and larger shrines were part of syncretic complexes known as miyadera run by Buddhist priests. Even the few independent institutions such as Ise and Izumo had close Buddhist connections, and Hardacre states that in Ise there were a scarcely credible 300 temples. Although the influential Yoshida Shrine in Kyoto operated a licensing system, there was no unified training system or common form of ritual. ‘In an institutional sense, says Hardacre, ‘Shinto has no legitimate claim to antiquity as Japan’s “indigenous religion”.’[2]

The forerunners of what is now known as Shinto were the Nativists of Edo times, often referred to as the Kokugaku movement. The scholars emerged out of Confucian study of the past and held that Japanese roots had a distinctive difference from those of China. Driven by thinkers such as Kamo no Mabuchi, Motoori Norinaga and Hirata Atsutane, a philosophy emerged that maintained Japan was superior to China, that the emperor should have supreme authority, and that the worship of kami was Japan’s true religion. Motoori Norinaga (1730-1801) was particularly influential in asserting the supremacy of Japan, driven by a loathing of the Chinese and their rationality. By contrast, the Japanese were held up as intuitive, harmonious, and naturally virtuous. Moreover, they had an unbroken imperial line descended from the gods, thus proving their divinity.

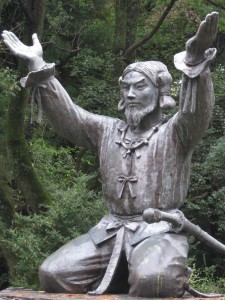

A statue of Okuninushi at Izumo Taisha welcomes spirits to the afterworld

Motoori’s research focussed mainly on philological matters and a desire to interpret Japan’s past through an aesthetic of ‘mono no aware’ (awareness of the transience of things). For his part Hirata took Mottoori’s notions of Japanese superiority to claim that all other religions, including Christianity, derived from the truths of Shinto. He had an interest in the supernatural and even investigated the mythical worls of tengu and kappu. He claimed that while the body putrifies after death, the spirit migrates to an afterlife world governed by the Izumo kami, Okuninushi.

Under Hirata’s influence the Kokugaku movement developed Motoori’s spiritual notions in a more political direction, which challenged the military control of the Tokuagawa shoguns. For the Kokugaku thinkers, Japanese were by nature inclined to revere the divinity of the imperial line, but the authority of the emperor had been usurped by military rulers. A mythical golden past was constructed when all was harmony under a beneficent father-figure blessed by descent from a heavenly sun-goddess. In this way an ideology was conveniently at hand for the Restoration movement of the 1860s, which under the guise of returning power to the emperor sought to overthrow a dysfunctional shogunate.

With the success of the Meiji Restoration in 1868, Buddhism was side-lined as the new government turned from the religion of Tokugawa Japan to the creation of something new – something that in the West would be considered Paganism. Indeed, when the first Catholic missionaries arrived in Japan in the sixteenth century, that’s just how they did regard what to them was the bizarre worship of sun, rocks, trees and spirits.

Leave a Reply