This is the final part of a series comparing the Pagan traditions in Japan and Britain. The previous post looked at the invention of Wicca and the growth of Neo-paganism in Britain in modern times. Now we turn to the reforms to Shinto made by the Meiji government after 1868. (For previous parts in the series, please search under the Paganism category to the right.)

*******************************************************************************************************

Buddhist supremacy

In the nineteenth century the situation in Britain and Japan had certain similarities, in that a dominant axial religion had incorporated popular folk elements. Buddhism was not only the official religion of Tokugawa Japan but an important part of state control, since everybody had to be registered with a temple. Shinto, in the words of Helen Hardacre, was ‘a mere appendage’. There were localised cults with independent lineages, but there was no central authority. Moreover, there was no unified training of priests. Indeed, there were precious few ‘Shinto priests’ (perhaps just 5%), since the vast majority of kami worship was conducted by Buddhist monks, Shugendo practitioners, shamans, or village elders. (17)

The Tokugawa regime privileged Buddhism to such an extent that even Shinto priests had to register with Buddhist temples. Most of the shrines too were under Buddhist control, and larger shrines were part of syncretic complexes known as miyadera run by Buddhist priests. Even the few independent institutions such as Ise and Izumo had close Buddhist connections, and Hardacre states that in Ise there were a scarcely credible 300 temples. Although the influential Yoshida Shrine in Kyoto operated a licensing system, there was no unified training system or common form of ritual. In an institutional sense, says Hardacre in Shinto and the State 1868-1988, Shinto did not exist before 1868.

The forerunners of modern Shinto were the Nativists of Edo times, referred to in Japan as part of the Kokugaku movement. They emerged out of Confucian study of the past and held that Japanese roots had a distinctive difference from those of China. Driven by thinkers such as Kamo no Mabuchi and Norinaga Motoori, a way of thinking emerged that maintained Japan was superior to China, that the emperor should have supreme authority, and that the worship of kami was Japan’s true religion.

Motoori Norinaga was particularly influential in asserting the supremacy of Japan, driven by a loathing of the Chinese and their rationality. By contrast, the Japanese were held up as intuitive, harmonious, and naturally virtuous. Moreover, they had an unbroken imperial line which was descended from the gods, proving their divinity.

According to Norinaga, the emperor would by rights be revered by the populace at large, as in the mythical past, but the authority of the emperor had been usurped by military shoguns. This had led to neglect and impoverished conditions for the imperial family. In this way an ideology was conveniently at hand for the Restoration movement of the 1860s, which under the guise of returning power to the emperor sought to overthrow a dysfunctional shogunate.

The Re-forming of Shinto

When the Restorationists came to power, they drew on the ideas of Kokugaku to foster an emperor-centred state. To boost the political restructuring of the nation, they sought an ideology and turned to the idea of a state-sponsored religion. In this they were inspired by the role of Christianity in the West, which in Britain had given enthusiastic support to the civilising role of colonisation in spreading the word of God to the unenlightened and illiterate.

The new state religion was promoted as a conscious rejection of the previous Tokugawa Buddhism, and the enforced split of the two religions was far from amicable. In some cases the elements had to be forcibly torn apart. Complicating elements such as Shugendo were dealt with ruthlessly by being banned in 1872, and its adherents forced to choose between Shinto and Buddhism. (The ban was only lifted in 1947.)

Shugendo was abolished by the Meiji reformers, and followers forced to choose between Buddhism and Shinto

The ‘construction’ of the new state religion is covered in detail in Hardacre’s Shinto and the State 1868-1988. Published in 1989, it was written by a professor at Griffith University in Australia (now Reischauer Professor of Japanese Religions and Society at Harvard). The book shows how one of the key objectives of the Meiji reformers was to bolster the authority of Ise, and thus the emperor, and thereby those who ran the state in his name. Ise was seen as the seat of the primal ancestor, Amaterasu no okami, who had supposedly founded the imperial lineage. It was thus the emperor’s ancestral shrine, and the young Emperor Meiji made a point of going to visit it, the first of his family to do so since the supposed visit of Empress Jito in the seventh century.

To emphasise the supremacy of the emperor in the new scheme of things, shrines were ranked in a hierarchy with Ise at the apex. In addition, 70 Daijingu, or Kotai Jingu, were established as branches of Ise to promote the imperial shrine nationwide. Moreover, it was asserted that every household should have an Ise talisman in its kamidana (spirit shelf). At the same time emphasis was given to Yasukuni as a place to commemorate those who had died in the service of the emperor – a new idea. The imperial bias of the new regime was reflected in the great Pantheon Debate when Okuninushi no mikoto, the deity of Izumo Taisha, was excluded despite claims to being lord of the underworld. Unlike officially sponsored kami, which derived from the Yamato state, Okuninushi was from Izumo and traced his lineage through Susanoo, a brother and rival to Amaterasu. For an ancestral religion, such matters were of key importance.

Between 1903 and 1920 there was a massive state-sponsored reorganisation of shrines, the effect of which was to reinforce the imperial connection in rural and remote areas. A ‘one village one shrine’ policy led to the closure of thousands of shrines housing obscure or unnamed local deities – according to Hardacre, some 83,000 shrines disappeared nationwide during this period. In many cases officially sanctioned imperial kami were installed in the new combinatory shrines. These were joined by new shrines erected in honour of imperial ancestors (Kashihara Jingu, erected in 1889 and dedicated to the mythical Emperor Jimmu is an example). At the same time tombs of the emperor’s lineage were ‘discovered’ by experts as part of a campaign to promote the sanctity of an imperial line descended in unbroken line from the gods. (Many of the discoveries were dubious, invented or mistaken.) (18)

The overall effect was the creation of a unified religion with an imperial ideology, in which loyalty to the emperor was posited as the greatest good. It was utterly different from anything in the past. ‘Nowhere else in modern history do we find so pronounced an example of state sponsorship of a religion – in some respects the state can be said to have created Shinto as its official “tradition”,’ is Hardacre’s conclusion. (19)

The path to State Shinto

Whereas kami worship had often been conducted without a Shinto priest in Edo times, rituals were now performed by a priesthood trained by a centralised organisation. The Imperial Rescript on Education strengthened the notion of imperial divinity, and the idea was spread that Shinto rites were not religious but a part of national life. Hardacre notes that priests were eager to embrace these reforms, since it brought them state patronage, though the general populace were less enthusiastic. The effect was that Shinto as an institution became a servant of state, and as the country moved towards militarisation, the new religion fell in behind it. ‘A strong association between Shinto and war was the inevitable result,’ writes Hardacre, ‘and the priesthood voiced no reservations about the use of shrines to glorify death in battle.’ (20)

The excesses of the war period are well-known, and in a study by D.C. Holtom the blame for this was laid at the door of State Shinto. There is a tendency to think of State Shinto as having been decisively dismantled by American reforms in the Occupation Period. Hardacre suggests otherwise, noting that the Meiji-era institutions have remained essentially in place. Moreover, ‘the priesthood overwhelmingly favors a return to the prewar situation,’ she states. One factor she doesn’t mention is the effect of hereditary succession on priests’ attitudes, as a high percentage (possibly 50% according to one estimate) come from Shinto households which benefitted from the Meiji reforms. Like their grandfathers, they owe their vocation and livelihood to the privileging of Shinto in Meiji times.

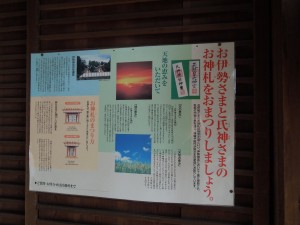

A poster at Yasaka Jinja urging shrine members to buy an Ise talisman, part of Jinja Hocho's post-Meiji Ise-centric policy

The allegiance to Meiji-style Shinto is reflected in the policies of the National Association of Shrines (Jinja Honcho), established in 1946, which continues to devote the bulk of its efforts to bolstering the authority of Ise. In their book A New History of Shinto (2010), Breen and Teeuwen have noted the deleterious effect of this on the finances of local shrines, which are coerced into buying Ise amulets in order to resell them to their parishioners. Similarly the efforts of the ruling party (LDP) to legitimise Yasukuni serve similar ends in being in Hardacre’s words, ‘a clear reassertion of prewar values’. Visits by self-declared nationalists such as Koizumi Junichiro and Abe Shinzo are obvious examples. The invented traditions of the Meiji Restoration thus continue to set the country’s religious and political agenda.

For grass-roots believers, there is however another way – that of time-honoured traditions, of local practices, of community festivals, fertility rites and sacred rocks. It’s a vision of Shinto far removed from the murky world of Meiji reforms and Yasukuni parade-grounds. It’s an alternative Shinto. A Shinto for a new age – one that will throw off the shackles of the past. A Shinto not of narrow nationalism, backward-looking and regressive, but a forward-looking Shinto of hope and environmental internationalism. A Green Shinto.

Leave a Reply