High priest of the Asatru Association, Hilmar Örn Hilmarsson, leads a procession at the Pingvellir National Park near Reykjavík. Photograph: Reuters

Neopagan religions like Wicca have been on the rise in the West since the 1970s. Their appeal lies in the reclaiming of an affinity with nature and ancestral spirits, as well as an absence of doctrine and dogma. This has gone along with a desire for spirituality in an age marked by the waning of belief in Christianity, with its patriarchal values.

Now in an article from The Guardian news comes of a revival of the old ways in Iceland, with a strong environmental element underpinning a symbolic and psychological attachment to the gods of old. As such there’s much in common with Shinto, which like other pagan religions is polytheistic and nature oriented. The big difference of course is that Shinto has been sponsored by the state since Meiji times, whereas neo-pagan religions in the West remain minority beliefs at odds with the mainstream.

As the article below points out, paganism can take on elements of nationalism through the glorification of deities particular to a race or people. But modern times are crying out for a new form of borderless environmentalism. Perhaps sometime in the future, when neopaganism has become more established, an international alliance of pagan religions will emerge which embraces Shinto as a fellow faith. Like-minded people guided by the wisdom of the past and reaching out in the spirit of global collaboration – now there’s a vision for the future.

*************************************************************

Back for Thor: how Iceland is reconnecting with its pagan past

by Esther Addley The Guardian, Feb 6, 2015

On Thursday, Hilmar Örn Hilmarsson, who lives near Reykjavík, flew to the tiny fishing town of Höfn on Iceland’s south-east coast to conduct a marriage ceremony. He is not a churchman or a registrar; in fact, he is a pioneering film composer and musician who has collaborated with Sigur Rós and Björk among others. But thanks to his position as high priest of Iceland’s neo-pagan Ásatrúarfélagið or Asatru Association, he has an authority formally recognised by the Icelandic state to conduct marriages, name children and bury the dead.

The ceremony itself, Hilmarsson said shortly before departing, would be a simple one: after performing a hallowing ritual to sanctify the space, he would read from one of Iceland’s celebrated epic poems and then invoke three ancient Norse gods and, “as a countermeasure”, three goddesses including the fertility deity Freyja. The couple would then grasp a large copper ring and make vows to each other, and that would largely be that. “It’s a short ceremony; there’s no preaching because the idea is it’s the couple who are marrying themselves, and I just sanctify that.”

Hilmarsson has conducted more than 200 weddings during his time as high priest, but he and the Norse pantheon of Thor, Odin, Freyr and Frigg are likely to find themselves even busier in future. In the 12 years since he took over its leadership, membership of the Ásatrúarfélagið, which the Icelandic government recognises as a formal state religion, has increased sixfold. In March, after decades of planning, the group will start building what is almost certainly the first temple to the pagan Norse deities since Iceland was officially converted to Christianity in 1000AD.

Norse deities rise from the dead to capture the imagination of new generations

Not that this is a religion like many others. He may be building a temple to Thor and his fellows, but Hilmarsson says he doesn’t pray to the Norse gods or worship them in any recognisable sense, nor does he believe in the literal truth of the texts – the treasure-trove of 13th century Icelandic “Eddas” recording the mythology of earlier times – on which the religion is based. He cheerfully admits that the rituals and blods or gatherings that the group practises are no more than creative reimaginings of how pre-Christian Norse people related to their deities.

“So yes, it’s partly a ‘romantiquarianism,’” he says of his faith. “But at the same time, we feel that this is a viable way of life and has a meaning and a context. It is a religion you can live and die in, basically.”

Happily for him and the group’s 3,000 members, the Icelandic government agrees, meaning that the organisation is entitled to a share of the religious taxes that each Icelandic citizen is obliged to pay. The result, after more than a decade of careful saving, will be the wooden-clad new temple or hof, built on a quiet section of Reykjavík’s shore with a wall of south-facing glass designed to capture the rising and setting sun on the shortest day of the year.

There, the group will gather for weekly study and for the five main feasts of the year when, under the leadership of a robe-clad Hilmarsson, they will gather around a central fire, recite the poems, make sacrificial drink offerings to the gods – unlike some pagan groups they do not practise animal sacrifice – and feast on sacred horsemeat.

Honouring the mystery of life is a universal trait

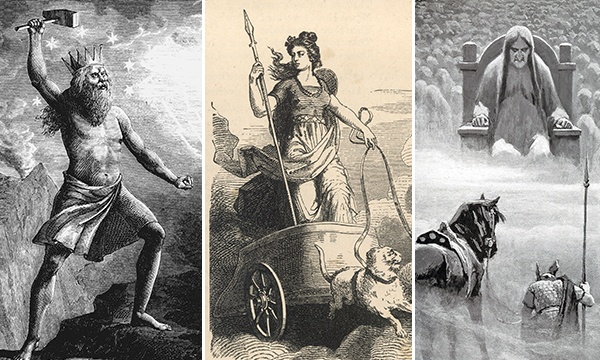

By the time the Icelandic Eddas were written down in the 13th century, an active belief in the pantheon of historic gods they describe was already archaic. For centuries, however, the Viking world from Iceland to the Black Sea had been shaped by belief in the central world-tree of Yggdrasil, the hammer-wielding god Thor, the one-eyed, raven-attended Odin and a host of elves, trolls and nature spirits.

Rosa Thorsteinsdóttir, a folklorist at the University of Iceland’s Institute of Icelandic Studies who has been collecting and archiving the country’s oral legends, says it is impossible to know whether the pre-Christian stories survived in the oral folklore after the country’s conversion, but even after a millennium of Christianity, nature beliefs never quite died out. “People tell fairy stories of the hidden people; there are nature spirits that walk over the country and you should not disturb them. These stories are alive.”

Her own name, she notes, is derived from Thor’s stone – “there are many, many names in Iceland linked with Thor”. Interest in the Norse myths revived, as elsewhere, in the late 19th century, and again in the spiritually conscious 1960s and early 1970s, when the Edda manuscripts were returned to Iceland from Denmark.

The reason for the recent flowering in neo-paganism among Iceland’s young is less easily explained, however. On a mild Wednesday evening in central Reykjavík, a group of a dozen or so members have gathered for the organisation’s weekly reading group, to pore over the elder Edda. Several of those present are in their 50s, but more than half are twentysomethings. The atmosphere is less that of a ritualised session or religious prayer meeting than a lively Chaucerian study group with beer and biscuits, in which members interrupt a lively debate to share their delight in a favourite image or metaphor.

Thor has a hammer, Daikoku has a mallet. Commonalities between pagan religions are the norm rather than the exception.

Linus Orri, a thoughtful 25-year-old environmental activist, says he thinks the group’s appeal lies in the fact that “in a world that is quite artificial, here there seems to be an interest in the real, something authentic – whether that’s searching for some older wisdom or the truth about how society was, or whether it’s [our] commitment to nature, I can’t really say”.

“Also, the group is so incredibly inclusive. You get a really unpretentious group of people for some reason. Nobody would pretend to be having a conversation with Thor, for example.”

Unlike some neo-pagan societies across the world, the group has been careful to permit no space for far-right ideology and has severed all ties with outside organisations (“Some of them are really pissed off that a stupid hippy nation should have the sources in their own language,” says Hilmarsson.)

For Sólveig Anna Bóasdóttir, a professor of theology and ethics at the University of Iceland, the growth of paganism may be explained by the country’s complicated relationship with Christianity – in one sense, Iceland is a highly secular society, but she says 90% of 14-year-olds still undergo confirmation in the state Lutheran church, which remains rich and powerful thanks to the country’s religious taxation.

Though equal marriage, for example, is now accepted in the state church, she believes many were disillusioned by the long debate over the issue, and by a more recent spat (“I think it was simply racist,” says Bóasdóttir) over whether to permit Iceland’s first mosque to be built near Reykjavík.

“In Iceland we don’t really have this situation with the evangelical churches on the rise. Rather, it would be these alternatives that are quite moderate, like the Ásatrúarfélagið, that hold the appeal. People respect them.”

*************************************

For a guide to the Viking deities, see here:

http://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/feb/04/thor-odin-norse-gods-guide-iceland-temple-vikings-deities

For a discussion of paganism and Shinto, see the series on Pagan Pasts beginning with this one here.

Pagan cloth offerings on a pathway to Mt Fuji – a coming together of East and West

Hi John,

I love it when you report on Paganism in the West! As we have both pointed out, even modern Shinto has more similarities with Western Pagan practices (both pre- and post-Christianity) than it does with monotheist religions.

I wanted to post a small bit of caution for your readers who might be interested in a Neo-Pagan or Reconstructionist faith.

As I mentioned in the commentary on my piece RE: Kemetan faith, if you’re looking into joining a group that follows the particular pantheon in which you are interested, here are some tips:

1. Approach with care! Don’t assume that because you and the group is a fan of Thor or Zeus that you share core values.

2. Ask a lot of questions. Be specific and direct about what you want from the group and what the group might want from you.

3. If members of the group use certain phrases or words that might indicate they are not simply a circle, moot or other gathering of like-minded pagans but a cult…run away…quickly…the terminology of cults (in this case…religious movements that ask for the dissolution of the individual into the group mind) normally involve phrases like “everything is love” or “the leader is god” Any group that asks you to cut ties with your friends and family is a cult. Any group that requires you to pay money for its teachings is a cult. Any group that requires you to have sex with other members is a cult. Any group that preaches racial, gender or other types of absolute superiority is a cult.

Again, I love modern Paganism. I love its lack of hierarchy, holy books and messiahs. I love its eclectic nature (like the ability to worship deities of different pantheons and have no one flinch). I love its belief in magic and the supernatural in general. However, I have…in my many years of being Pagan, come across some truly twisted individuals/groups. So, if you’re looking to join up with some others for wild rumpus, bonfire-y, middle of the forest, Pagan fun…just know who you’re hanging out with before hand. :)

I wrote this this morning without coffee. Lack of coffee often causes me to overgeneralize. The reason that I wrote this is because there are some Asatru/Odinist groups that are white supremacists. There are some Wiccan groups that believe that their “Great Rite” is essential for understanding the relationship between the “god and goddess.” There are groups like Scientology (they are not pagan, they believe in aliens) who charge their members. There are other groups of pagans that try to separate you from your friends and family because “they are your new family.” All of these groups use techniques for controlling and manipulating people. They are not true Pagans. You will probably never meet any of these people. They are as fringe and out-in-left-field as David Koresh or Jim Jones. I felt it was necessary to mention because the Pagan community has no governing body or even an umbrella term to which they refer themselves. This is both a blessing and a curse. The lack of governance and establishment means anything goes. You can decide you are the reincarnation of Merlin (hey, it could happen) or tell people you have seen visions of the Flying Spaghetti Monster. As long as you’re not hurting anyone…no problem. The curse, of course, is that some do horrible things and say they’re one of us…they are not.

Thank you for the words of warning, Malaz. Of course all groups are open to abuse, and it’s well to be wary and to retain an independent perspective. Aum Shinrikyo that used sarin gas and tried to acquire nuclear weapons are a prime example of how religion can be corrupted.

Blind faith is no virtue, and Green Shinto is dedicated to keeping a critical eye on matters…

“blind faith …” That reminds me. I’ve been giving this idea a lot of thought in the past few years. You should do a Green Shinto piece on the differences in what various cultures call “faith” For example, in India they have the “devotee” who is literally “in love” with their chosen deity, however, most Asian countries don’t even consider the word when discussing their practice.

Thank you for the input, Malaz. I don’t know much about the Hindu tradition, so I asked my Indian friend who replied as follows: “As far as Hinduism is concerned, the scriptures all tell us again and again not to believe anything that is said or written, not even in the scriptures, but to experience everything first hand and only then to accept it. Exactly what Buddha preached. … the being in love with a deity is bhakti or devotion, not faith. And it is often romantic in nature. Some very beautiful poems from the poet saints of centuries ago are quite graphic about their desire for physical union with their god. Faith on the other hand is of two types: astikya which is “belief’, and vishwas which is faith. And andhvishwas is blind faith. So a believer in god is called an astik, and a non-believer is called nastik. A believer has faith in the existence of god and his powers etc. And andhvishwas is believing in babas and god men and superstition etc. Which is what true gurus are always trying to fight.”