Does taking part in a festival make one religious? Does celebrating Christmas make one Christian? The boundaries between religion and tradition are far from clear.

People often describe the Japanese as not religious. Indeed, the Japanese themselves often say as much. Yet social life in Japan is undeniably characterised by religious behaviour and religious institutions carry great weight. Take the multitude of religious festivals, for instance, or the role of lucky charms and Buddhist funerals. It’s something that perplexes many observers and the graph below provides an example of the conundrum.

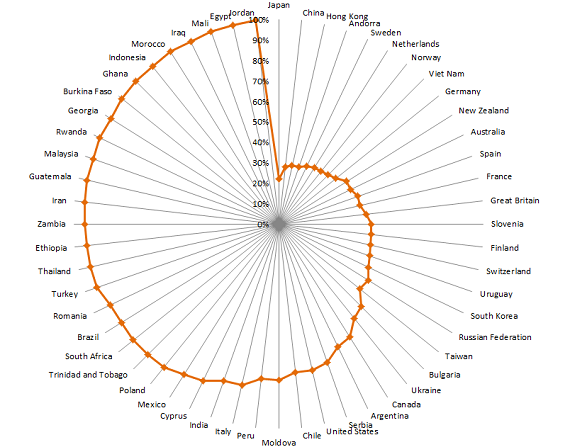

The importance of religion in our everyday life (OneEurope website)

On a graph of 56 countries, Japan stands at the absolute low point of religious “belief”

This infographic was made on the basis of a survey meant to determine the importance of religion in people’s everyday life. The factors considered were, frequency of regular religious services attendance, frequency of prayers, participation in religious activities, visits to the church (any house of worship) during childhood, existence of religious objects in the home and so on.

The study concluded that in 36 out of 56 surveyed countries religion is ‘very or rather important’ to the majority of its people, regardless of the type of faith they believe in. The numbers differ a lot from one region to another, with 100% of Jordanians and Egyptians considering religion very important in their life, while only 20% having the same answer in Japan and China!

A family performing the 7-5-3 ritual. A religious activity, or a Japanese custom?

However, without more information on the technique and questions used the results of this survey can’t be trusted. It begs the question, what is “religion”? The survey refers to “organised” religion not beliefs per se, and Western norms are used as the determining factor.

For example, few Japanese people go to church/temple/etc. regularly but most have a Buddhist altar and often a Shinto kamidana in their house. Visits to graveyards once or more times a year are common, and there are numerous memorial services too. Life in Japan is framed by customs and festivals that are religious in origin but no longer perceived as “religion”.

It’s all a matter of definition. At shrines and temples one will invariably see a devout worshippers, which is enough to suggest that far from being irreligious Japanese have a strong sense of the spiritual. They may not classify this as belonging to a religion however, more a matter of custom and tradition.

Paying respects to the kami, reading a fortune slip and buying an amulet do not necessarily imply the ‘worshippers’ are Shintoist. But they do show conformity to Japanese tradition and the practice of their ancestors.

Though this person shows deep respect for the spirit of the tree, she does not call herself a Shintoist.

Leave a Reply