Placing valued objects in the coffin or grave was common practice in ancient times. Here a Viking burial is shown with shield and sword accompanying the warrior to the next world.

This is the fourth in a series of articles about the Shinto funereal practices, adapted from an academic article by Elizabeth Kenney. (For a link to the original article, see Part I.)

******************

Encoffining

The chief mourner and other relatives assemble in the room. There is seldom a priest present. Holding the futon, the mourners lift the corpse and put the corpse and futon together into the coffin. They then cover the body with a new futon.

Various symbolic objects or items especially valued by the deceased may go into the coffin, too. I have heard of a fishing rod, a pipe, books, a doll (“to keep her company”), clothes, rosaries, make-up, a comb, the deceased’s umbilical cord (very common), blank white paper “money” (shades of China!), and real 1,000-yen bills.

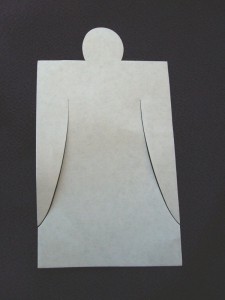

The paper doll ‘scapegoat’ used to remove impurities

(One can’t help but speculate that the doll is a vestige of the Sino-Japanese custom of putting clay figures into a grave. At the same time, since in Japan dolls (usually paper) are used in purification rites, the doll in the coffin might function as a scapegoat for the spirit of the deceased. It is worth noting that the doll I heard about was not an old-fashioned paper cut-out, but a regular plastic baby doll.)

Next, the coffin is closed and, in some cases, purified (in which case, a Shinto priest will be asked in). Next, the family members purify themselves by washing their hands and rinsing out their mouths. This is the hand-washing rite that reoccurs several times during the funeral rites.

When the coffin has been set in its proper place, the mourners sit in front of it. The chief mourner bows and everyone follows. Close family members offer food. The mourners then bow in order of closeness to the deceased. The food may be cleared away or left there. Finally, the chief mourner bows, the other mourners do likewise, and they all leave the room.

In ancient times ‘haniwa’ clay figures used to accompany burials

The encoffining was traditionally done under the direction of a Shinto priest. However, in today’s Japan, it is more often a ceremony directed by an employee of a funeral company, who leads the family through the proper steps.

The coffin must be set up in the manner in which it will remain for a day or two. Behind the coffin stands a folding screen. The coffin is placed on benches so that it is raised up. A photo of the deceased may be propped up in front of the coffin. A small table with the protective sword is placed to the right of the coffin, near the head of the deceased.

As many as three long, narrow tables are placed in front of the coffin: on one are placed the awards, medals, commendations, and so forth, that the deceased had received in life; another table is for the food offerings; and on a third are placed tamagushi. Pairs of sakaki and lanterns (lights) may also be set up in front of the coffin. The whole area should be enclosed with curtains on three sides.

A priest prepares to hand a tamagushi offering to participants to present to the kami.

Leave a Reply