Sincerity, loyalty, self-sacrifice. Zen or Shinto values?

Sincerity, loyalty, self-sacrifice. Zen or Shinto values?

Mindfulness is a key concept in both Zen and Shinto. Purification and egolessness too.

Harae (purification) and kegare (impurity) in Shinto resemble Delusion and Attachment in Buddhism. The goal in both religions is similar, though the means are different.

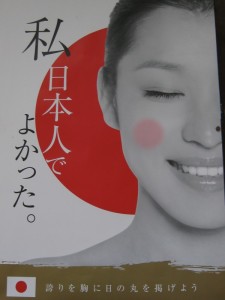

A Shinto poster promoting patriotism

In Shinto people look to restore their kami nature by visiting shrines and praying to the mirror (the pure soul of Amaterasu). In Buddhism they look to restore their original Buddha nature and look to the mirror as a symbol of egolessness. Both strive for a spotless mirror that reflects without the distortions of the ego. In one case the mirror is a gift from the kami; in the other it is a product of one’s own endeavour.

Consider the following quotation. It’s written by D.T. Suzuki, but it seems to me it could equally apply to Shinto as much as to Zen.

The sword has thus a double office to perform: the one is to destroy anything that opposes the will of its owner, and the other is to sacrifice all of the impulses that arise from the instinct of self-preservation. The former relates itself with the spirit of patriotism or militarism, while the other has a religious connotation of loyalty and self-sacrifice. In the case of the former very frequently the sword may mean destruction pure and simple, it is then the symbol of force, sometimes perhaps devilish. It must therefore be controlled and consecrated by the second function. Its conscientious owner has been always mindful of this truth. For then destruction is turned against the evil spirit. The sword comes to be identified with the annihilation of things which lie in the way of peace, justice, progress, and humanity. It stands for all that is desirable for the spiritual welfare of the world at large.

– Suzuki, Zen Buddhism and Its Influence on Japanese Culture, pp. 66-67.

One thing Suzuki is at pains to emphasise is that acts of war are objectionable when carried out for egoistical ends. However, a sincere and selfless sacrifice is to be regarded as virtuous. He praised the Zen connection with Bushido as promoting a sense of selflessness. Submitting to a higher authority thereby becomes an absolution for the act of killing.

Read through Shinto writings and you will find much the same kind of thinking. Patriotism is fiercely upheld. Since the good of the nation is equated with the figure of the emperor, its heroes are those who sacrificed themselves for the imperial institution while its enemies are those who stood in opposition. Yasukuni’s cult of the kamikaze pilots is an obvious example of self-sacrifice being exalted as a supreme virtue.

At Ise Jingu, the country’s premier shrine, the tradition is that you never pray for things for yourself. That would be a sign of selfishness. By contrast you should express gratitude – gratitude to the kami and the imperial descendant. In the great communal enterprise of pilgrimage to the national shrine, self is subjugated in the larger entity of the nation, symbolised in the person of the emperor. Subjugation of self thus lies at the core of Shinto, just as it is in Zen.

Sincerity, loyalty, self-sacrifice. These are very much common to Shinto and Zen. Perhaps they offer an example of the way in which the indigenous culture helped shape the transformation of Chinese Chan into Japanese Zen.

A demonstration of Kendo at Shimogamo Shrine in Kyoto, put on to please the kami

A celebration of Samurai virtues at a Shinto festival in Tohoku

Leave a Reply