Judging by the popularity of Inari among non-Japanese Shinto sympathisers, it would seem that fox guardians have a special appeal. There’s certainly something about the liminal creatures that appeals to the imagination. Perhaps it helps explain why Inari shrines and subshrines are so numerous across Japan. It seems nearly every major shrine has a small Inari shrine somewhere on the precincts.

Judging by the popularity of Inari among non-Japanese Shinto sympathisers, it would seem that fox guardians have a special appeal. There’s certainly something about the liminal creatures that appeals to the imagination. Perhaps it helps explain why Inari shrines and subshrines are so numerous across Japan. It seems nearly every major shrine has a small Inari shrine somewhere on the precincts.

That great folkorist, Lafcadio Hearn, explored the appeal of ‘Kitsune’ over a hundred years ago, helping to preserve for us some of Japan’s ancient traditions that have since died out. It is part of his litany of ‘Lost Japan’, as he portrays the forces of modernisation steadily destroying the charming customs of the past.

The following extracts come from his chapter on ‘Kitsune’ in Glimpses of Unfamiliar Japan (1894)

************************

“By every shady wayside and in every ancient grove, on almost every hilltop and in the outskirts of every village, you may see, while travelling through the Hondo country, some little Shinto shrine, before which, or at either side of which, are images of seated foxes in stone. Usually there is a pair of these, facing each other. But there may be a dozen, or a score, or several hundred, in which case most of the images are very small. And in more than one of the larger towns you may see in the court of some great miya a countless host of stone foxes, of all dimensions, from toy-figures but a few inches high to the colossi whose pedestals tower above your head, all squatting around the temple in tiered ranks of thousands. Such shrines and temples, everybody knows, are dedicated to Inari the God of Rice. After having travelled much in Japan, you will find that whenever you try to recall any country-place you have visited, there will appear in some nook or corner of that remembrance a pair of green-and-grey foxes of stone, with broken noses. In my own memories of Japanese travel, these shapes have become de rigueur, as picturesque detail.”

“Inari the name by which the Fox-God is generally known, signifies ‘Load- of-Rice.’ But the antique name of the Deity is the August-Spirit-of-Food: he is the Uka-no-mi-tama-no-mikoto of the Kojiki. In much more recent times only has he borne the name that indicates his connection with the fox-cult, Miketsu-no-Kami, or the Three-Fox-God. Indeed, the conception of the fox as a supernatural being does not seem to have been introduced into Japan before the tenth or eleventh century; and although a shrine of the deity, with statues of foxes, may be found in the court of most of the large Shinto temples, it is worthy of note that in all the vast domains of the oldest Shinto shrine in Japan-Kitzuki-you cannot find the image of a fox. And it is only in modern art-the art of Toyokuni and others-that Inari is represented as a bearded man riding a white fox. Inari is not worshipped as the God of Rice only; indeed, there are many Inari just as in antique Greece there were many deities called Hermes, Zeus, Athena, Poseidon-one in the knowledge of the learned, but essentially different in the imagination of the common people. Inari has been multiplied by reason of his different attributes. For instance, Matsue has a Kamiya-San-no-Inari-San, who is the God of Coughs and Bad Colds – afflictions extremely common and remarkably severe in the Land of Izumo. He has a temple in the Kamachi at which he is worshipped under the vulgar appellation of Kaze-no-Kami and the politer one of Kamiya- San-no-Inari. And those who are cured of their coughs and colds after having prayed to him, bring to his temple offerings of tofu.”

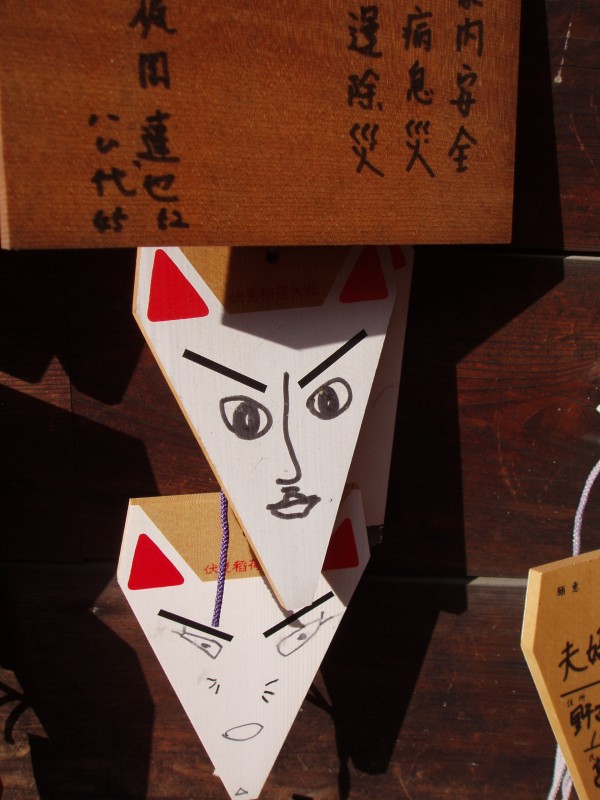

Inari subshrine with white fox guardians

“…the old conception of the Deity of Rice-fields has been overshadowed and almost effaced among the lowest classes by a weird cult totally foreign to the spirit of pure Shinto-the Fox-cult. The worship of the retainer has almost replaced the worship of the god. Originally the Fox was sacred to Inari only as the Tortoise is still sacred to Kompira; the Deer to the Great Deity of Kasuga; the Rat to Daikoku; the Tai-fish to Ebisu; the White Serpent to Benten; or the Centipede to Bishamon, God of Battles. But in the course of centuries the Fox usurped divinity. And the stone images of him are not the only outward evidences of his cult. At the rear of almost every Inari temple you will generally find in the wall of the shrine building, one or two feet above the ground, an aperture about eight inches in diameter and perfectly circular. It is often made so as to be closed at will by a sliding plank. This circular orifice is a Fox-hole, and if you find one open, and look within, you will probably see offerings of tofu or other food which foxes are supposed to be fond of. You will also, most likely, find grains of rice scattered on some little projection of woodwork below or near the hole, or placed on the edge of the hole itself; and you may see some peasant clap his hands before the hole, utter some little prayer, and swallow a grain or two of that rice in the belief that it will either cure or prevent sickness. Now the fox for whom such a hole is made is an invisible fox, a phantom fox – the fox respectfully referred to by the peasant as O-Kitsune-San. If he ever suffers himself to become visible, his colour is said to be snowy white. According to some, there are various kinds of ghostly foxes. According to others, there are two sorts of foxes only, the Inari-fox (O-Kitsune-San) and the wild fox (kitsune).

“To define the fox-superstition at all is difficult, not only on account of the confusion of ideas on the subject among the believers themselves, but also on account of the variety of elements out of which it has been shapen. Its origin is Chinese; but in Japan it became oddly blended with the worship of a Shinto deity, and again modified and expanded by the Buddhist concepts of thaumaturgy and magic. So far as the common people are concerned, it is perhaps safe to say that they pay devotion to foxes chiefly because they fear them. The peasant still worships what he fears.

“The old Shinto mythology is indeed quite explicit about the August-Spirit-of-Food, and quite silent upon the subject of foxes. But the peasantry in Izumo, like the peasantry of Catholic Europe, make mythology for themselves. If asked whether they pray to Inari as to an evil or a good deity, they will tell you that Inari is good, and that Inari-foxes are good. They will tell you of white foxes and dark foxes-of foxes to be reverenced and foxes to be killed-of the good fox which cries ‘kon-kon,’ and the evil fox which cries ‘kwai-kwai.’ But the peasant possessed by the fox cries out: ‘I am Inari-Tamabushi-no-Inari!’ – or some other Inari.

*****************

The following comment on Hearn’s observation comes from a paper entitled “The Gothic Traveler: Generic Transformations in Lafcadio Hearn and Angela Carter” by Mary Goodwin of the National Taiwan Normal University.

In “Kitsune” [Glimpses of Unfamiliar Japan, 1894], Hearn devotes a long essay to the subject of fox images in Japanese rural culture, covering all aspects of fox lore, including their supposed supernatural power, rumors of demonic possession, madness caused by fox magic, foxes that are goblins and those that transform into beautiful women. Hearn carefully details how profoundly the fox culture has influenced the behavior of the local people, including how beliefs about the dangers of foxes influence property rights and value: “the land of a family supposed to have foxes cannot be sold at a fair price”. Fox culture even affects the marriage chances of young women; those whose families have foxes may be considered a bad risk as a daughter-in-law.

Leave a Reply