(Pics from google)

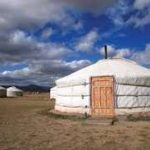

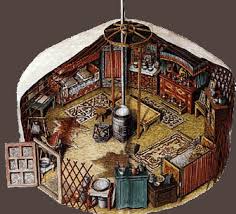

The traditional ger (Mongolian tent), aligned to the south, is more than a portable tent for it also serves as spiritual sanctuary. In the north stands an altar with mirror, so that any evil spirit entering the tent is frightened off by its own reflection. The central pole serves as a domestic axis mundi, allowing access to both upper and lower worlds. Men are seated on the left and women on the right to facilitate a yin-yang flow of energy, and in the middle of the tent is a fire above which an opening enables the smoke to escape. It is through that opening that the shaman’s soul soars when taking flight.

The group ate to the accompaniment of Buryat folksongs, the first of which was about the falling snow, another about the beauty of the mountains, and a third about the greatness of Chingis Khan. One of the instruments comprised two strings of horse-hair along a piece of wood carved to resemble a horse, and if you shut your eyes the sound sent you galloping away across the plains.

All of a sudden I was startled from my thoughts by the strangest of noises, as if an otherworldly voice had spoken from the space above us. For a moment my heart beat anxiously as I looked around for an explanation of the source, and slowly it became apparent that someone was doing traditional throat singing. Even then the effect was unnerving, for the reverberations were deep, guttural and quite unhuman.

Afterwards one of the musicians, a teacher at the Ulan Ude’s music academy, explained that throat-singing may have originated from the wind whistling round the side of the ger and reverberating through the openings. People wanted to mimic the noises, which vibrated simultaneously in different pitches, and as they strained ever harder to capture the sounds they developed their vocal chords and created new effects.

Eventually the noises took on otherworldy qualities, with shaman-singers using the techniques to project the voice of the spirits with which they communicated. It was the shamanic way of speaking in tongues. Most of his students took a year or so to acquire the skill, he told us, though some were incapable. When done properly, it didn’t hurt at all and was known to be good exercise for underused muscles.

The Siberian shaman’s costume has a fringe covering the face, which acts as a protective veil. The official reason is to shield viewers from the unnerving sight of a spirit taking possession of the shaman. From one of the musicians we learnt that even for those versed in such matters, the phenomenon cold be perplexing. ‘I was at a shaman’s session once,’ he said, ‘and the spirit’s voice was so deep and bass that when the fringe was raised afterwards and I saw it was a woman, I got a weird feeling and gooseflesh all over.’

Leave a Reply