Shaman flags of the Buryat Mongols near Irkutsk

As elsewhere, Buryat shamans not only have a strong connection to the land, but they serve as guardians of the cultural identity. Under Communism, however, the ethnic distinctiveness was seen as threatening to the party’s official line of universalism. In the interests of uniformity they tried to stamp out shamanism altogther.

The Saio-dai’s headdress in Kyoto’s Aoi Matsuri is suggestive of the shamanic miko of early history

The motivation was reminiscent of the way seventh-century Japan had clamped down on shamanic activities in the name of centralisation. Women in trances uttering messages from an unseen world did not meet the needs of the expanding Yamato state, and a network was established of imperial shrines with male functionaries. Miko (female shamans) were suppressed or incorporated into the new institutions in subordinate roles, with formal ceremony replacing spontaneity. As ritual became a matter of correctness, shamanism was replaced by Shinto.

The ‘fossilised remains’ of shamanism remain evident in today’s Shinto. The ethereal noise uttered by priests to mark the descent and departure of the kami, for example. It’s a nod towards shamanic possession, but it’s pure form.

If one can presume that ancient Japanese had close links with Korean shamanism, and that Korean shamanism derived from that of Siberia through southern migration, then it would be surprising if there were not close affinities between Shinto and Mongolian shamanism. My journey to Siberia seemed to bear that out.

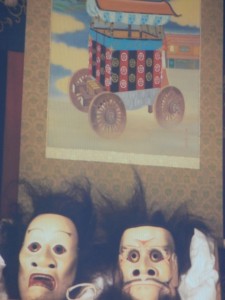

Shaman masks, now treasures of Kyoto’s Gion Matsuri

Shamanism in general is animistic, polytheistic, and aims to establish balance between humans and spirits. There are countless deities, including ancestral spirits of place and beings that live in the upper world. There’s no fixed doctrine and no holy books. Ancestor worship blends into a sense of sacred nature. All of that applies to shamanic cultures – and to Shinto too.

Many if not most religions make a fetish of threesomes. Three in one; the Buddhist triad; the three Wise Men. Even atheistic communism came up with Marx, Engles and Lenin. Personally I’ve always attributed this to the father-mother-child template of human life, but psychologists ascribe it to the workings of the mind along past-present-future lines. In shamanism too there is a threefold reality in terms of an upper, middle and lower world, and this is reflected in the Buryat tradition. The human self is divided into body, breath and soul; blessings are done in threes; there are three parts to the soul; and the sick are given life extensions of three or nine years. Worship involves walking three times round an ovoo shrine. There are nine disciples for a shaman, and there are 99 heavenly spirits, triply divided and subdivided. So how about Shinto?

Unsurprisingly, three also lies at the very core of the religion. The triple tomoe mark is the tripartite symbol of Shinto, borrowed from Taoism where it represents Earth, Human and Heaven. There are three imperial regalia that show descent from the sun-goddess (mirror, sword and jewel). Purification is done by waving a stick with paper streamers three times. There are three cosmic children born of the first ever misogi (cleansing), Amaterasu, Susanoo and Tsukinomikami, and you walk three times through the chinowa circle of purification. But perhaps most striking of all is the wedding ceremony of san-san-kudo (3-3-9), by which couples exchange three times three cups of saké to signify eternal union.

Jingu Kogo, shaman leader in Japanese mythology, here part of Gion Matsuri

Mythologically there are close parallels too. In Mongolian folklore the sun goddess Naran Goohon becomes sick and makes the world dim but is restored after a meeting of the gods. In Shinto, Amaterasu retreats into a cave and throws the world into darkness, but light is restored after a meeting of the gods.

In Mongolian mythology a rainbow connects the upper world and this world. In Shinto the two worlds are joined by Ama no Ukihashi, the floating bridge of heaven (ie a rainbow). Both Shinto and shamanism privilege intuition as a means of knowledge, typically in the form of dreams which are interpreted as messages from the spirits. They may disclose sacred sites or events of special significance; indeed, the location for many Shinto shrines are revealed in this way (most famously Ise Jingu when Amaterasu appears in a vision to say that she is ready to stop her wanderings).

In both traditions the pollution of the material world contrasts with the purity of the spirit world. Spirits are offended by disrespect, lack of hygiene, the violation of taboos, or contact with blood and death. Consequently purification is carried out before rituals with such means as smoke, salt, fasting and washing. A ‘spiritual cleaner’ is used to sweep away impurities, known as minaa in Mongolian and haraigushi or onusa in Japanese. The minaa can be used like a whip to clear negative energy; applied to the body it acts as a means of healing.

Mongolian ‘minaa’ used to whip away impurities (courtesy 3worlds website)

For Buryats trees are a manifestation of earth’s power, and remarkable trees represent a special mark of the life-force. Ribbons or silk scarves are tied to their branches, whereas in Japan sacred trees are marked with a shimenawa rice rope. In both Mongolian and Shinto traditions, human spirits are thought to remain behind after death as protector and helper of the household. After several generations they no longer remain as individual entities but merge into an anonymous whole. Those who exhibit exceptional power, such as Chingis Khan and Nobunaga, are worshipped as deities regardless of any moral considerations. In both traditions, people who die too young or unjustly may plague descendants and need placating. Those who are too strongly attached to things in this world may linger on unrequited.

In both traditions a ‘spirit-body’ is constructed out of objects such as wood and rock, or simply a doll or paper drawing. The spirit is drawn into the object in a special rite conducted by the shaman or priest. In shamanism the rhythmic repetition of the drum, quickening in tempo, leads to an altered state of consciousness. In Shinto the drum is used in shrines at the beginning of rituals with a quickening beat, as if to alert worshippers to the arrival of an unseen presence.

In Mongolia bells and rattles attract the attention of spirits; in Shinto a bell is rung to call the kami. While dancing miko use a kind of rattle (suzu) to catch the kami’s attention, another legacy from shamanism. In both religions the mirror plays a central role in terms of using divine light to disspell evil spirits. Mirrors on the shaman’s costume provide protection as well as facilitating possession by ancestral spirits by providing portals. In Shinto the mirror in the shrine symbolises the supreme source of life, the spirit of the sun-goddess herself.

Mirrors can be hung on costumes as in shamanism or as part of the misakaki in Shinto

Terrific information! Thank you!!

Thanks for the positive feedback and encouragement…