Meoto (husband-wife) rocks can be found around Japan, but the most famous pair are at Futami near Ise, as pictured above. The rocks are usually taken to represent the primal pair of Izanagi and Izanami. Meoto rocks are invariably located in water and tied together in symbolic union by a shimenawa rope. The piece below, exploring similarities in other cultures, is extracted from a longer article on the Japanese Mythology and Folklore website. (For the full article, see here.)

************************************************************************************************

The embracing Sky Father, Mother Earth and Heavenly Ropevine

by heritageofjapan

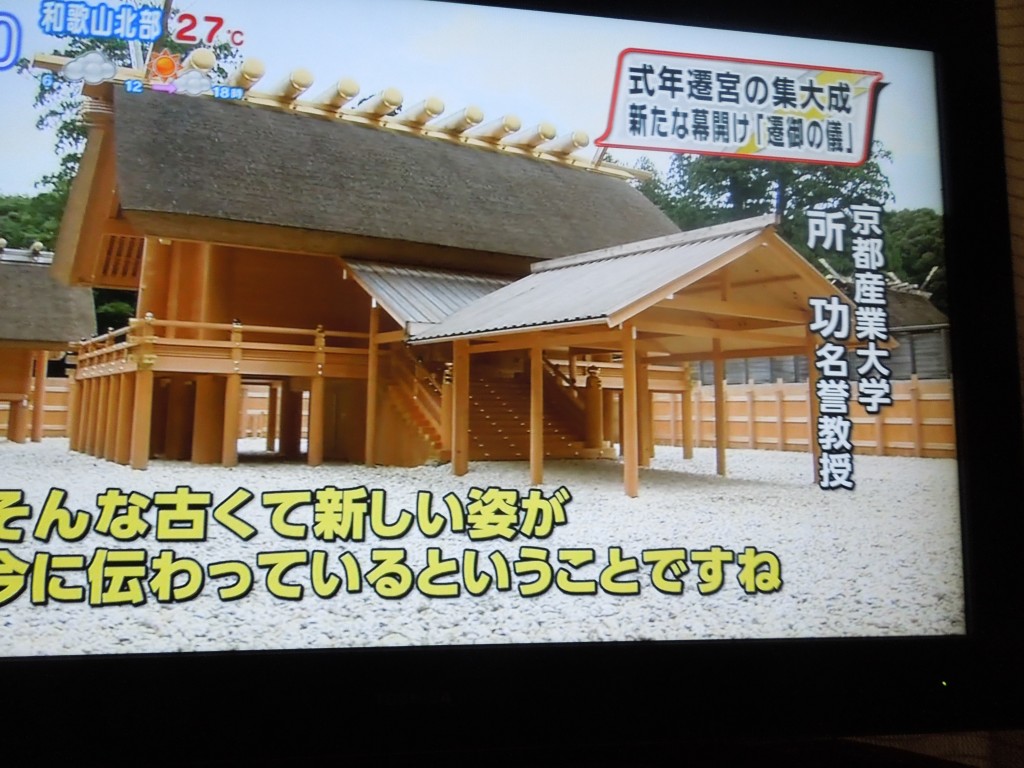

Meotoiwa, “husband and wife rocks”, or the Wedded Rocks, are a couple of small rocky stacks in the sea off Futami, Mie, Japan. They are joined by a shimenawa (a heavy rope of rice straw) and are considered sacred by worshippers at the neighbouring Futami Okitama Shrine.

Izanagi and Izanami stirring the primordial slime to create Japan

According to local lore and Shinto beliefs, the rocks represent the union of the creator kami, Izanagi and Izanami. Although the above Futami Meioto Iwa rocks are the most famous ones, there are many others to be found elsewhere in the Japanese landscape.

Such iconography and the idea of a Creator-Couple or Cosmic Couple is rampant throughout the ancient prehistoric world, and particularly widespread among the tribes of the Austro-Asiatics, the Austronesians as well as the Polynesians. Stephen Oppenheimer writes about the mythical belief on p. 321 of his book Eden in the East: The Drowned Continent of Southeast Asia:

The story of creation with Sky Father locked in close and dark sexual union with Mother Earth, is found in a band stretching from NZ to Greece. The locked-couple picture is seen at its fullest in a little understood string of islands, the Lesser Sundas of eastern Indonesia. And in the surviving megalithic societies of Sulawesi, Maluku and the Nusa Tenggara, a concept of Father Sky and Mother Earth, who were previously locked in a tight embrace remains central to cultural beliefs.

What does the heavenly rope vine symbolize and what is its origin? Below we explore some possible ideas and explanations for the celestial ladder twine.

The straw rope tying the husband and wife together is a visual metaphor recalling the myth from Flores Island (an island arc extending east from Java island of Indonesia). A rope twine used to tie the Sky Father and Earth Mother together until a dog chewed up the vine, causing the two to fly apart, a mythical explanation for the separation of Sky and Earth.

Is the shimenawa rope, often used as a signifier in Shinto, indicative of the tie between this world and the other?

In ‘Ayahuasca, shamanism, and curanderismo in the Andes‘, Steve Mizrach examines the concept of an otherworldly “soul vine”, a concept that seems to have been diffused to the Americas from the Altai-Siberia or Mongolia. In Brazil, there is a term ‘ayahuasca’ that comes from the Quechua, meaning literally “the vine of souls,” — it is also called “the visionary vine” or the “vine of death.” The folk term refers to the botanical species of liana known as Banisteriopsis Caapi , which is also known as Yage among the Indians of Brazil. The Andean shaman uses Yage, “the vine of souls,” to contact the dead as well as to divine the location of water. Mizrach thus draws a connection between the vine as a connector between the Underworld with passages of water.

Perhaps one of the “ceremonial” uses of the lines is for the shaman to travel during his “spirit journey,” guiding him like a magnet to the places of the dead where he can bargain for water. Indeed, during their “soul flights,” shamans typically report that they are “guided” on their journey by “spirit paths” that lead them to the appropriate destination.

The Ladder-to-Heaven documents a ladder made of reed or vine among the South American tribes (the Nivalke, the Mataco, the Tupi, Sikuani and the Chorote)… In Myth in History: Mythological Essays, Peter Metevelis (p. 255) tabulates the countries that possess a myth of ropeway access to the Upperworld as including Iceland, India, China, Japan, Korea, Indonesia, Melanesia, North and South America, and Polynesia.

In the case of Japan, the straw vine appears as a boundary marker that marks off where the entrance to the Underworld or Heavenly River is, and it is used to quickly fence off the entrance after Amaterasu emerges from the Iwato cavern, thus preventing the Japanese sun goddess from returning to the Underworld. This myth is said to be closest to the myth found in the Indo-Iranian Vedic literature — of Usas, the Dawn woman and heralder of the rising sun, who is hidden in a cave on an island in the middle of the Rasa stream at the end of the world (see Michael Witzel in his Vala and Iwato The Myth of the Hidden Sun in India, Japan and beyond).

Whether the celestial rope as a heavenly ladder, road or path to and from heaven, originated from Africa or is found there as a result of back migrations, we do not know. African sacred traditions of the Dinkas speak of heavenly path or rope that men once traversed freely to and from heaven to converse with the gods, but which collapsed or was destroyed in primeval times as a result of an accident, after which Heaven became separated from Earth.

Indeed since the emergence of the Judeo-Christian tradition, awe is the mandatory reaction that the true believer is required to have towards God. From this perspective the sense awe and wonder is bounded and regulated through the medium of religious doctrine. In contrast, those of us who believe that it was not God but humans who are the real creators are unlikely to stand in awe of this allegedly omnipotent figure.

Indeed since the emergence of the Judeo-Christian tradition, awe is the mandatory reaction that the true believer is required to have towards God. From this perspective the sense awe and wonder is bounded and regulated through the medium of religious doctrine. In contrast, those of us who believe that it was not God but humans who are the real creators are unlikely to stand in awe of this allegedly omnipotent figure. We all have the capacity and the spiritual resources to experience the mysteries of life and the unexpected events that excite our imagination through a sense of wonder. Those who stand in awe of God internalise their sense of wonder through the medium of their religious doctrine. Their response can possess powerful and intense emotions. But the way they wonder is bounded by their religious beliefs and their conception of God. In a sense this experience of spiritual sensibility is both guided and ultimately dictated by doctrine and belief. Historically those religious people who dared to go beyond these limits risked being denounced as heretical mystics.

We all have the capacity and the spiritual resources to experience the mysteries of life and the unexpected events that excite our imagination through a sense of wonder. Those who stand in awe of God internalise their sense of wonder through the medium of their religious doctrine. Their response can possess powerful and intense emotions. But the way they wonder is bounded by their religious beliefs and their conception of God. In a sense this experience of spiritual sensibility is both guided and ultimately dictated by doctrine and belief. Historically those religious people who dared to go beyond these limits risked being denounced as heretical mystics.