Sacred groves bring light, life and greenery to Japan's often concrete-encased cities

What trees would you find in a Buddhist grove that you wouldn’t find in a Shinto grove? It’s a puzzle answered by one of my favourite columnists, Keven Short, in The Japan News today, though judging by the Kyoto weather his headline is somewhat premature. 4C at midday doesn’t feel much like spring! (Short is a naturalist and anthropology professor at Tokyo University of Information Sciences.)

*************************************************************************************************************************

February 06, 2014

Kevin Short / Special to The Japan News

Spring is here at last!

At least in the traditional Asian koyomi calendar, this past Tuesday marked Risshun, or the official start of spring. In the lunar reckoning, the first moon of the New Year has been waxing toward first quarter. The setting Sun, in turn, has been slowly climbing up and over the snow-covered slopes of Mt. Fuji.

This year I’m continuing my study project on Japanese sacred groves. Almost all Shinto shrines are surrounded by a grove of old-growth trees. Even urban shrines will often have a few ancient oaks or keyaki zelkovas. Folklorists believe that the Japanese originally worshipped their kami deities in dense groves of tall trees. Later, actual shrine buildings were constructed to house the deities, but the traditional animistic cosmology was continued in sacred trees and groves.

Although not as well known as those of Shinto shrines, some Buddhist temples also support a substantial grove of protected trees. The Buddhist cosmology is infused with a strong ecological ethic. All living creatures are thought to derive their life energy from the same universal source.

(courtesy Kevin Short)

Temple groves often contain species of trees that are almost never found around Shinto shrines. These are trees that are considered sacred to the Buddhist faith. A typical example is the bodaiju lime tree. According to Buddhist tradition, the historic Buddha Shakyamuni (Shaka-Nyorai in Japanese) obtained enlightenment while meditating under the branches of a sacred fig tree (Ficus religiosa).

Buddhism later spread from India westward into Pakistan and from there eastward along the old Silk Road trading route to China. The sacred fig, however, is a tropical species that does not thrive in the cool temperate zone. The Chinese thus substituted a native tree with similar-looking heart-shaped leaves. The priest Eisai, founder of the Rinzai sect of Zen Buddhism, is said to have brought the first bodaiju to Japan sometime in the late 12th century.

The small white lime flowers bloom in midsummer. They are extremely fragrant, and are a favorite of honeybees. The flowers are attached to a distinctive structure called a bract. Later, when the small hard fruits develop, the bracts turn aerodynamic, dropping off intact and carrying the still-attached seeds away on the wind.

In Japan, fibers pulled from the inner bark of the native species were traditionally used to weave cloth and baskets, and to make paper. The temple bodaiju, being protected trees, are not used for this purpose, but the hard fruits are sometimes strung together to make simple Buddhist juzu rosaries.

Another tree often seen around temples is the mukuroji soapnut tree. This deciduous species is native to the warmer areas of western Honshu, Shikoku, Kyushu and the Ryukyu Islands, as well as to Taiwan and the southern Asian mainland. The large leaves are compound, with an even number of small leaflets attached in a featherlike pattern along a long central axis. Tiny flowers bloom in midsummer. The berries ripen in autumn and consist of a single, very hard, round, black seed inside a leathery rind.

The rind of the mukuroji fruits contains copious amounts of chemicals called saponins. When stirred or shaken in water, these chemicals produce abundant foam. Many species of plants contain saponins, which botanists believe may help make the plants poisonous or at least unpalatable to certain insects. Throughout the world people have traditionally used these foamy plants as shampoos, soaps and laundry detergents. Soaps made from the mukuroji rinds are still available at natural cosmetics stores.

The hard black seeds of the mukuroji can be polished to a beautiful sheen, and are used to fashion high-quality juzu rosaries. The saponins are found only in the rinds, not in the seeds themselves, which actually contain edible oils that can be extracted and used for cooking. In addition, there are old folk beliefs that the mukuroji trees have a magical power to protect children from illness. The kanji used to write the tree’s name can be interpreted as something like “No (mu)—Illness (wazurai)— Child (ji).”

A sense of the sacred in the shrine precincts of Togakushi Jinja in Nagano

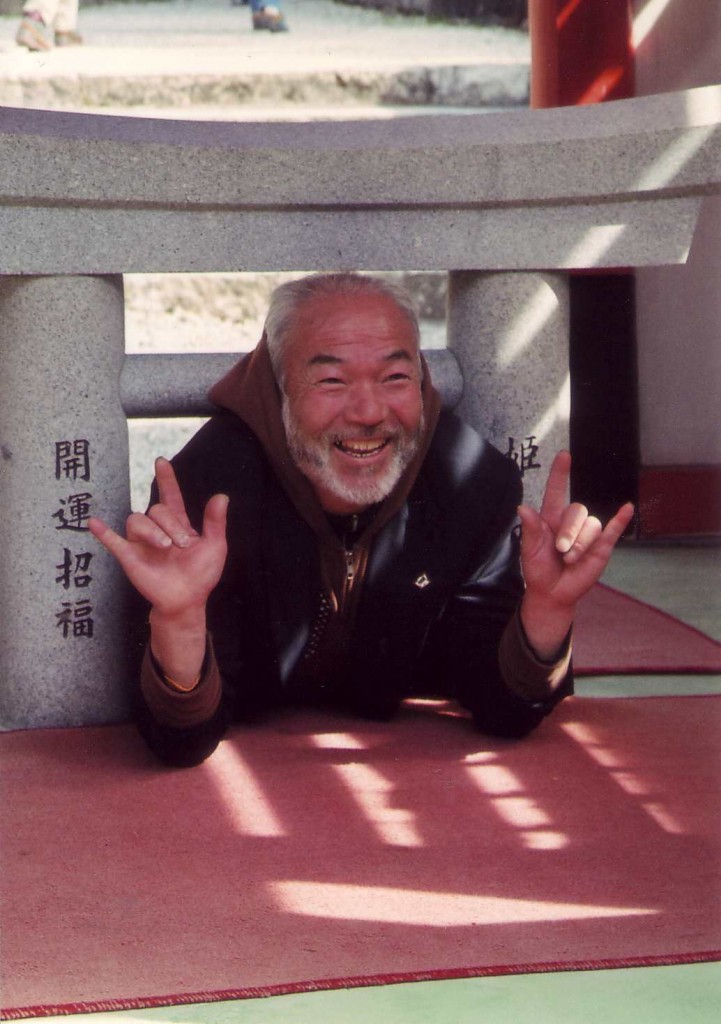

But just because something’s sacred doesn’t mean it can’t be used for amusement. One example is shown in the first photo, which is a scene from the Flower Festival at the Awashima shrine in Unzen, Nagasaki. (You might remember that Unzen was the location of some severe volcano eruptions in the early 1990s.)

But just because something’s sacred doesn’t mean it can’t be used for amusement. One example is shown in the first photo, which is a scene from the Flower Festival at the Awashima shrine in Unzen, Nagasaki. (You might remember that Unzen was the location of some severe volcano eruptions in the early 1990s.)

The deer in Nara Park are wild animals designated as a protected species. It was said that at the time the Kasuga Grand Shrine, a World Heritage Site, was first built, the god of Kashima Shrine came in a white deer when it was transferred to the new shrine. Since then, they have been revered as messengers of the gods and thus carefully protected.

The deer in Nara Park are wild animals designated as a protected species. It was said that at the time the Kasuga Grand Shrine, a World Heritage Site, was first built, the god of Kashima Shrine came in a white deer when it was transferred to the new shrine. Since then, they have been revered as messengers of the gods and thus carefully protected.