The Kyoto Shinbun recently carried a half-page profile of Shinto scholar, John Breen (click here for his Wikipedia page).

The newspaper notes that he has a high reputation for scholarship and investigates matters that Japanese scholars are hesitant to research. One example is the controversial history of Ise Jingu, which in former times had a pleasure area between the Naiku and Geku. The Meiji government got rid of it as part of its campaign to sanctify the shrine, though as Breen points out there remain strong secular tendencies in the souvenir shops and stalls that pander to tourists.

Breen’s parents were Catholic, and his father was head of the BBC East Asia service. As a youngster he read Mishima and Endo Shusaku, which made him want to learn more. The Hidden Christians had a particular resonance for him, and he became interested in Japanese history. He went to Cambridge and did Japanese medieval studies, one of only four students on the course, then after graduating came to Japan to teach at a school in Kochi. In 1993 he earned a PhD at Cambridge, writing a dissertation entitled ‘Emperor, State and Religion in Restoration Japan’. (Later he became a lecturer at SOAS in London, and is currently associate professor at the International Research Center for Japanese Studies in Kyoto.)

In his comments about Shinto, Breen notes that kami worship was localised before the Meiji Restoration, and that the centralisation since then has been an innovation, not a reversion to an earlier time. Kami have two faces, he notes, a rough aspect as well as a benign, which makes them different from a merciful and benevolent God. It makes them closer to human beings in fact.

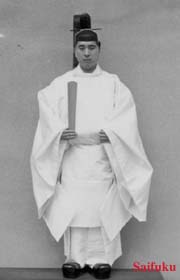

As for Ise, about which Breen is writing a book, he says he was fortunate to attend the shikinen sengu ritual (click here for a report), which he sees as a unique expression of the culture. ‘National authority and civil identity’ runs the headline. He says the current importance of the shrine derives from the time of Emperor Meiji, who signified its new primacy by visiting it in 1869. Before him there are apparently no records of visits by ruling emperors, so this was a dramatic change in policy. Since then stress has been given by the state to its supreme significance, such that imperial representatives and the prime minister attended this year’s ritual.

The Kyoto Shinbun carries a final thought: Breen would like young people in Britain to be more aware of Japan’s rich heritage rather than just being absorbed by manga and anime. Perhaps Martin Scorsese’s planned film of Endo Shusaku’s Silence, about Hidden Christians, will grab the attention of both the scholarly Breen and the anime-loving British youth!

********************************************************************************************

For more about Hidden Christians, click here.

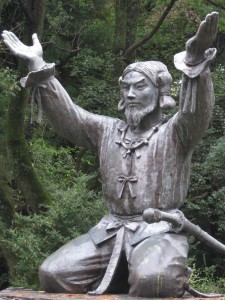

Below: A Hidden Christian (hidden no more) reads an orashio prayer at an ecumenical gathering at Karematsu Jinja in Sotome (Nagasaki), which in the age of persecution served Hidden Christians as cover for their worship.