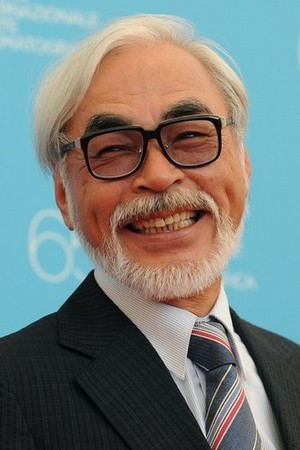

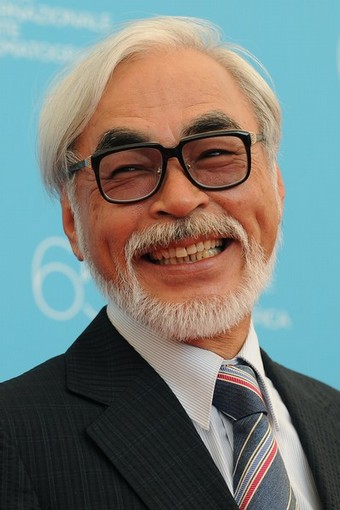

The very special spirit of place on Yakushima was celebrated by Hayao Miyazaki in the anime film, Princess Mononoke

Sanctifying sacred space is a key element in Shinto. The sense of the numinous is evident in its shrines and sacred rocks. Most of the ‘power spots’ which have won popularity in recent times relate to Shinto.

In an interesting article in Britain’s Independent newspaper, the author questions the modern practice of destroying houses where mass murder or other atrocities have occurred. Despite the secular, scientific notions of the age, the supposition seems to be that something related to the event lingers in the fabric of the building – something that might in Shinto be called kegare, or pollution. The destruction can be seen as an act of ‘cleansing’ or purification.

As D.H. Lawrence once wrote, ‘Different places on the face of the earth have different vital effluence, different vibration, different chemical exhalation, different polarity with different stars: call it what you like. But the spirit of place is a great reality.’

******************************************************************

By Brian Masters Independent 08 Aug 2013

The destruction of the house in Cleveland, Ohio, where three women were imprisoned for more than 10 years by Ariel Castro, a former school-bus driver, is a bizarre undertaking. There is no question that terrible things happened within those walls, that the three young women were deprived not only of their freedom but of their dignity, reduced to featureless sexual playthings for their jailer, a man whose desires were vile and unpredictable. He was arrested, charged, tried, found guilty, and last week was sentenced to life in prison, plus 1,000 years. That is as it should be, and justice has been demonstrably met.

Sanctifying the spirit of place

But what is meant to be achieved by removing the house in which the crimes were committed? The house is merely the décor to those crimes, and cannot in itself be considered part of the wickedness that corroded the lives of its inhabitants.

The immediacy of the destruction, within days of Castro’s sentencing, offers a clue. It is not a rational act, but an emotional one, and it must be done with speed, the better to effect the requirement to cleanse. In a dim, unfocused way, it is assumed that the building must be contaminated, and that its disappearance will exorcise the demons who despoiled it. The assumption holds that things can absorb what is loosely called “evil’, itself an emotional word which substitutes for explanation. This is a very old superstition, and its persistence into the modern era betokens the strength of its power to comfort.

It is obviously the imagination, rather than analysis, which is at work here, but it cannot be dismissed as unworthy of attention. Imagination can be an alternative route to truth, because it enables the unknowable, the unverifiable, the spiritual understanding that we all share, whether we are religious or not, to be brought to bear witness.

One must welcome the power of imagination to discern truth, while at the same time guarding against its tendency to reach false conclusions. It is perfectly proper to recognise that people may feel better because Castro’s house in Cleveland has been demolished, but unhelpful to claim that the demolition has purged the site of its evil.

Places can resonate with positive as well as negative connotations

We have seen this many times before. The house in Gloucester, where Frederick West visited such squalid torture and depravity upon many girls and young women over a protracted period of years was razed to the ground.

Centuries before, people identified as “witches” were burnt alive because it was simpler to wipe them away than to examine the questions raised by their alleged conduct or, even more, society’s irrational response to such questions. In the same way, it is now simpler to knock houses down than to comprehend the human nature which allowed vile acts to be committed within them.

I have had personal cause to experience whether or not “things” can be infected by the wickedness of people who once owned them. Dennis Nilsen, who murdered young men at two addresses in Muswell Hill and Cricklewood, north London, in the Seventies, was tried at the Old Bailey in 1983 and sentenced to life imprisonment. Neither of the houses in which he had a flat was destroyed and, as far as I know, there are people living in them now, presumably quite unaware of the history that they contain. And because they don’t know, they cannot be anxious about any such history.

Or can they? Might they not feel an involuntary, mysterious shudder pass through them if the spiritual legacy of such places lingers?

The presence of a spiritual dimension is testified by many of us who have “felt” it with the mind, despite its inherent illogicality, and places can be thought to be inhabited by good spirits as well as bad. You have only to spend some time among the war graves scattered over the Belgian fields, as I did earlier this year, to be touched by the hundreds of thousands of young soldiers, some barely out of adolescence, slaughtered there between 1914 and 1918 for the sake of a few yards of mud.

I could not see their faces, nor hear their voices, and did not recognise their names, yet they were there with me, in my head, with their loneliness and fear. That can only mean that the fields carry their memory – and what else is that but spiritual?

Then, too, if you are privileged to go beneath the altar at St Peter’s in Rome, where the original basilica built by the first Christians over the tomb of Peter has been excavated, at one moment you turn a corner into a room where the excavations have been suddenly halted, to leave a hole in the wall. And beyond the hole are some bones, said to be those of the apostle himself, in a direct straight line down from the mighty dome of Michelangelo.

This was once the man who knew Jesus, and you fall silent, engulfed with spiritual awe; in fact, you are struck dumb even before you see the bones, as the spirituality of the place announces itself in advance, and your imagination does the rest.

So, I find myself thinking, perhaps the house in Cleveland was better destroyed after all, just in case it carried a memory of what it witnessed. But we will never know. In these matters, there are only questions, not answers; suggestions, not certainty.

*******************************************************

Brian Masters is the author of Killing for Company: the Case of Dennis Nilsen and The Shrine of Jeffrey Dahmer

Avebury stone circle in England exudes a special kind of energy

“This movie is nothing more than a hymn to the Zero,” said one Internet commentator.

“This movie is nothing more than a hymn to the Zero,” said one Internet commentator.