Green Shinto friend, Amy Chavez, has an article on pilgrimage in The Japan Times, which follows below. She’s the author of the recently published Running the Shikoku Pilgrimage: 900 Miles to Enlightenment.

********************************************************************************

Amy Chavez making offerings at one of the shrines on the mini-88 temple course on the Seto Naikai island of Shiraishi, where she lives

Exploring Japan’s ancient past through pilgrimage

BY AMY CHAVEZ JUN 29, 2013 Japan Times

I’ve been running pilgrimages in Japan since 1997. So far, I’ve run the Shikoku 88-Temple Pilgrimage, the Mount Hiei Kaihogyo route in Kyoto (of the Tendai-shu monks), and tens of other smaller pilgrimages in Japan. If you are a runner in Japan, you should be running pilgrimages. If you’re a hiker, you should be walking or hiking them.

Pilgrimages are spiritual domains that encompass mountains, waterfalls, sacred rocks and miracle spots. There are pilgrimages to sacred places (reijo) such as the Kumano route to the Three Grand Shrines, or the Ise Shrine Okage Mairi that celebrates the Shinto goddess Amaterasu.

There are also circuit pilgrimages (junrei) such as the Saikoku Kannon Pilgrimage, a 33-temple route and the Shikoku 88-Temple Pilgrimage route (both Buddhist). On the Shikoku pilgrimage, the pilgrim visits a circuit of 88 sites that form a mandala, or spiritual map to the cosmos. In addition, there are hundreds of smaller pilgrimages, and replica pilgrimages throughout Japan. So, why not take your chances on the spiritual walking path?

These ancient pilgrimages are still alive and well in Japan, but most people don’t know about the smaller, lesser-known routes. The Japanese know, but they see them only for their original purpose: offering prayers to the various kami, bodhisattvas and Buddhas. And these days, few people are interested in doing this. It’s a wonder the Japanese have not thought of using the paths and infrastructure for exercise purposes instead. To my knowledge, the bodhisattvas are not opposed to a little exercise.

Pilgrims on their way to visit Nachi Shrine in Kumano

These pilgrimage routes offer plenty of diversions for the avid hiker or runner: a chance to bushwhack, get lost, fight off spiders and search for viable toilets. But with the proper preparation and practice, even these things will no longer be obstacles. The rewards for “following the path” are tenfold. A pilgrimage is a magical world you step into, brimming with history, beauty and solitude. And since few people are aware of them, you’ll have the whole route to yourself. Toilets too.

On these smaller pilgrimages, you will never encounter a school group on the trail (“Haro, haro?’), nor paved trails (and thus more shade) and nary a vending machine. Is this Japan?! You say, aghast. Yes, my friend, this is Japan, undiscovered. This is heaven.

The biggest barrier to hiking local pilgrimages is finding them. Despite these routes having been around for anywhere from 400 to 1,000 or more years, they’re usually fairly hidden. There’s probably a pilgrimage in your own neighborhood disguised among the buildings and concrete, but they are relics of Japan’s past and the Japanese people themselves have little interest in them.

So when it comes to asking around your neighborhood, look for a pious 80-year-old o-baachan. She’ll be able to give you very detailed information. The city or village hall is another good place to start since maintaining these historic routes lies with the local governments who may even have maps of them. You may decide these maps are pretty useless, but at least they confirm that a pilgrimage exists.

In the countryside, there is an interest in preserving the routes for historical reasons, even though the paths themselves are seldom used. Many small towns have a yearly organized pilgrimage route clean-up, where everyone gets together to cut weeds, clear debris and attend to the different gods and goddesses at the designated “stations” along the route. Shortly after, there may even be a neighborhood sponsored group hike to do the pilgrimage. This is the best time to investigate a pilgrimage! Not only are the trails in their best condition now, but you’ll have some good local guides to show you exactly where the route goes. Modern day roads, traffic lights and buildings may necessitate detours of certain parts of these old routes. The sacred sites themselves, however, remain.

Ise Jingu,Japan's prime pilgirmage destination in Japan

Most Japanese agree that a sacred site should not be disturbed, and will build around it accordingly. This leads to some interesting arrangements, such as one stone statue of the goddess Kannon on our island pilgrimage who was spared at the local rock quarry and now looks over it (no one was game to move the dame), and a Dainichi Nyorai Buddha who lives in what is now someone’s backyard. Usually, such people become the caretakers of that shrine. They keep fresh flowers in a vase next to the deity and sweep the area around the shrine.

Other times, a city will grow up around a pilgrimage, and the shrines may seem out of place among the cars, pollution and concrete of the city. You’ll find these deities poking their heads out from behind utility poles, or enduring hoards of passersby who don’t even stop to greet them. Be compassionate. Take pity on these poor stone deities and leave a small offering of some coins or a piece of fruit.

Your pilgrimage is bound to incorporate a bit of the geocaching element combined with the old summer camp intuition of a scavenger hunt as you seek locations of shrines built under large hanging rocks or down mysterious paths.

The trick to knowing a pilgrimage is doing it. The first time on any route, you’re bound to get lost a couple times. But once you know the trail, you can only improve on it and each time you’ll learn something new. It’s also a good idea to take a stick or hand towel with you just in case you meet some wrathful spiders building webs across the trail. Carry plenty of water and take note of the public toilets near each section of the route.

Pilgrimages can take anywhere from a few hours to a few days or even a month (as in the Shikoku pilgrimage) to complete, but most people break them up and do sections at a time. If you only want to do a few kilometers a day, that’s up to you. There are no hard and fast rules to free-form pilgrimaging. You can stop and give a little prayer or a mantra at each shrine, drop a few coins to the deity, or you can simply breeze on past with a friendly wave of recognition. With time, you may find yourself more and more drawn to pilgrimages. When you’re ready, the area residents will be happy to fill you in on the local folklore.

So get out there and indulge yourself in nature! The pilgrimage world awaits.

Descending the sacred Mt Miwa, where a one-hour pilgrimage leads up to the holiest site of early Yamato times

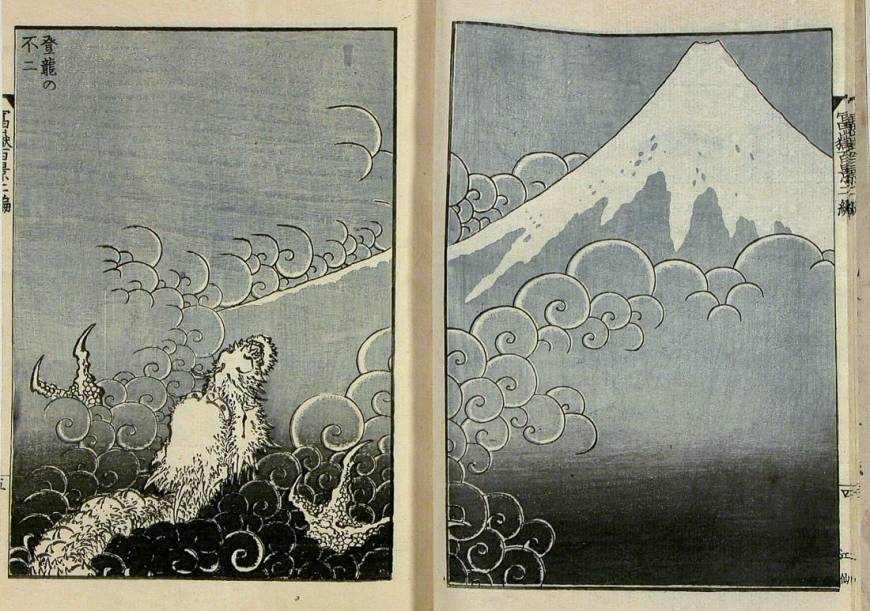

Many pilgrims no longer had to go to the mountain, as the mountain had now come to them. At the height of the Edo Period (1603-1867), there were more than 200 fujizaka, and none have been constructed since the 1930s. Fifty-six survive today, including those at Teppozu Inari Shrine in Tokyo’s Hatchobori district, and Hatomori Shrine in Sendagaya.

Many pilgrims no longer had to go to the mountain, as the mountain had now come to them. At the height of the Edo Period (1603-1867), there were more than 200 fujizaka, and none have been constructed since the 1930s. Fifty-six survive today, including those at Teppozu Inari Shrine in Tokyo’s Hatchobori district, and Hatomori Shrine in Sendagaya.