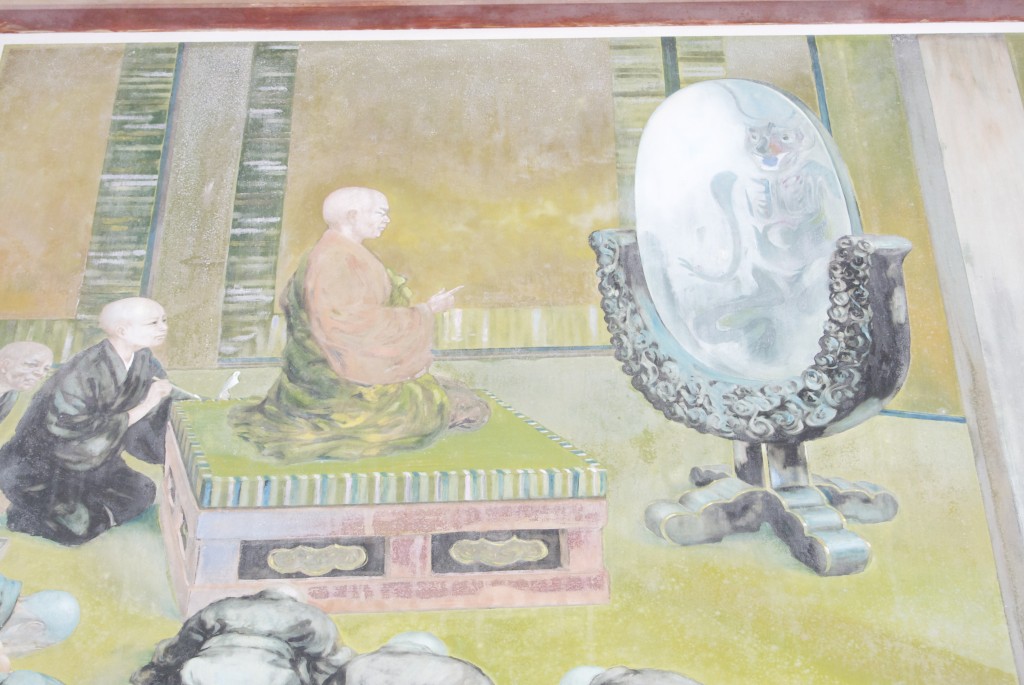

Sea and sacred mountain - spirituality of an island culture (pic Cultural Affairs Agency/Kyodo)

Heritage status will mean big changes

BY ERIC JOHNSTON MAY 2, 2013 Japan Tiimes

OSAKA – Local and prefectural governments and businesses surrounding Mount Fuji welcomed the news that the World Heritage Committee is expected to designate Japan’s most famous and popular mountain as a World Heritage site, despite concerns about what it will mean to the local environment and questions about how its preservation will be funded.

Long the most recognizable symbol of Japan, Fuji has been revered as a sacred mountain since ancient times. In the early Heian Period (794-1185), a Sengen Shinto shrine that enshrines Konohana-sakuya-hime, the goddess associated with volcanoes, was built at the base of the mountain’s north side.

In spiritual terms, Fuji is divided into three zones. The bottom, or Kusa-yama, is said to represent the everyday world. The forest line, or Ki-yama, represents the transient area between the world of humans and the world of gods, and the “burned” area, or Yake-yama, at the top is said to represent the realm of the gods, Buddha and death.

Thus, to climb Mount Fuji is to descend from the living world to the realm of the dead and then back, by which pilgrims can wash away their sins.

Efforts to get Mount Fuji, which drew more than 318,000 hikers last summer, listed with the World Heritage Committee date back to the mid-1990s, first as a U.N. Natural Heritage site.

However, when representatives from UNESCO visited Fuji in 1995, they were greeted with a sea of garbage and the smell of human excrement due to the lack of public facilities, and told Japan not to apply until the mountain was cleaned up.

After years of effort, there were toilets for about 15,000 climbers a day as of 2012. In the end, however, the government decided to try to get the mountain listed as a cultural, rather than natural, heritage site.

“The garbage problem was the reason why we applied for registration as a cultural site, and I have to say, it’s a great relief that we’ve been accepted,” said Shoichi Osano, a senior member of Fujiyama Gogo-me Kanko Kyokai (Mount Fuji Fifth Station Tourism Association).

For his part, Toshiyuki Kashiwagi, head of the industry and tourism department in Fujiyoshida, Yamanashi Prefecture, gave credit to the younger generation for pushing to clean up the mountain and get UNESCO’s approval.

“People in their 20s worked especially hard, showing just how conscious they are of its natural beauty and cultural importance,” he said.

The two tough questions Mount Fuji area residents and the central government now must answer are how to protect the mountain once it officially becomes a World Heritage Site and who to bill for those measures.

Discussions are under way in Shizuoka and Yamanashi prefectures on such issues as entrance fees for climbers. Although no rates have been set, the fee system could begin on a trial basis as early as this summer’s climbing season, which begins July 1.

“It’s likely we’ll ask that mountain climbers to help financially with keeping the mountain clean,” Yamanashi Gov. Shomei Yokouchi said in February.

In addition, in an issue sure to divide environmentalists and local businesses heavily dependent on the tourist trade, there is the question of what kinds of limits, perhaps legal in nature, to place on the number of climbers per day.

“Placing limits or restrictions on the number of entrants is something that still has to be discussed,” said Tetsuya Ikegaya, of Shizuoka Prefecture’s World Heritage office.