fortune slips at Heian Shrine (courtesy of traveladdicts)

Japan. past and present

Go to a shrine and one thing you’re sure to see: fortune slips tied up on a tree. The preoccupation with fortune-telling of young Japanese, females in particular, is striking. Where does it stem from? One place to look is the shamanistic roots of Shinto.

In ancient times Japan used a form of continental divination based on heating animal bones, such as the shoulder blade of a deer, so that it cracked. Then specially purified experts would ritually analyse the pattern of the cracks. After Yayoi times tortoise-shell came to replace animal bone, and from the Kamakura period divination became ever more diverse.

As well as dream interpretation there was footstep divination, which depended on the number of steps taken in a given direction, and bird divination which counted the number and direction of birds. My favourite is ‘roadside divination’, which involved going out to a crossroads and listening for clues in random bits of conversation like a living I Ching.

Shamans, past and present

Judging by the shops in Glastonbury, divination is just as popular amongst New Agers and neo-pagans as amongst Japanese. Oracle cards, runes, tarot, palmistry, astrology, clairvoyance, pendulums – there seems no end. The let-out is that if you don’t like the future on which you’re headed you can always create a new one.

Shamanic healer Kestrel, in front of a painting of the pagan goddess Bridget

Today I went to a shamanistic reading by Kestrel, one of Glastonbury’s most respected practitioners. The smell of herbs filled the air as he took some deep breaths and went into a rambling discourse on the state of my higher self. One thing I learnt was that I was going to retire to south-west England, near Totnes. Mmm. With the full moon shining on the Tor, I’m feeling at the moment I’d rather it was Glastonbury…

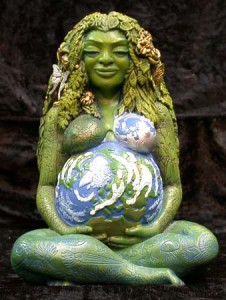

Neo-shamanism makes up a big part of the neo-pagan scene, and you have the feeling that paganism like Shinto must have grown out of shamanism. Rather than drawing down the spirits, shamans journeyed into the other world to seek aid in helping others in their community. Divination and healing formed a major part of their activities.

Healing, past and present

Last night at Glastonbury’s monthly pagan moot the discussion focussed on the healing power of particular herbs. Some of the members were practising witches, though there were also those with an interest in aromatherapy and other forms of healing. Matters medical took precedence over matters magical.

At some stage in history Shinto lost its healing and shamanistic aspects. I think this must have been during the seventh century. Buddhism took over exorcism and other forms of spirit healing at the imperial court. 0nmyodo (Yin-yang) experts cornered the market in divination. Shamans came to be seen as dangerous individuals who looked to the spirit realm rather than a worldly ruler. You can see why a supreme ruler wouldn’t be keen on them.

With the coming to power of the usurper Tenmu in 672, the imperial system as we know it began to take shape with a mythology based on descent from a sun-goddess. The details are pieced together in a book I’m currently reading – Imperial Politics and Symbolics in Ancient Japan by Herman Ooms. Fascinating stuff if like me you’re into this kind of thing!

|

|||