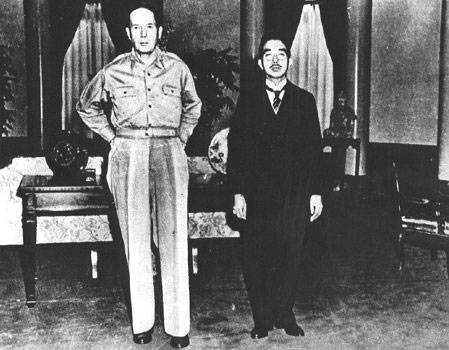

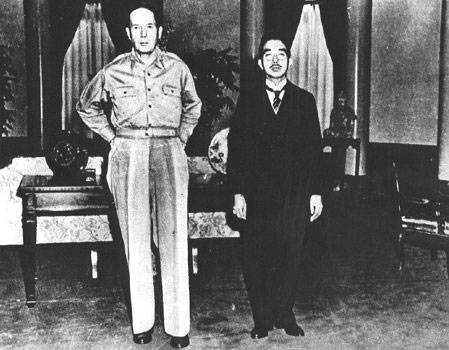

MacArthur towers over Hirohito at the end of WW2: the way seemed open to civilising the country with Christianity

What makes Japan so resistant to Christianity? It’s an intriguing question I tried to tackle in my book In Search of Japan’s Hidden Christians… Part of the answer, I believe, has to do with the nature of traditional beliefs found in Shinto and the security they offer Japanese… something Endo Shusaku referred to as a ‘mudswamp’. It’s interesting therefore to see what happened when State Shinto collapsed and a sustained attempt was made by MacArthur to Christianise the country…

**************************

Huffington Post: Did MacArthur Flood Japan With Religion?

By Suzanne McGee

c. 2011 Religion News Service

(RNS/ENInews) A new book on post-war Japan says Gen. Douglas MacArthur sought to fill the country’s “spiritual vacuum” with religious and quasi-religious beliefs, from Christianity to Freemasonry, as an antidote to communism.

In 1945 Under the Shadow of the Occupation: The Ashlar and The Cross, Japanese investigative journalist Eiichiro Tokumoto documents MacArthur’s efforts to persuade missionaries to intensify their efforts, even encouraging mass conversions to Catholicism.

“There was a complete collapse of faith in Japan in 1945 — in our invincible military, in the emperor, in the religion that had become known as ‘state Shinto,”‘ Tokumoto writes.

A number of documents Tokumoto used for research were declassified only recently, including accounts of a 1946 meeting between MacArthur and two U.S. Catholic bishops.

“General MacArthur asked us to urge the sending of thousands of Catholic missionaries — at once,” Bishops John F. O’Hara and Michael J. Ready later reported to the Vatican. MacArthur told them that they had a year to help fill the “spiritual vacuum” created by the defeat.

Based on his experience in the Philippines, MacArthur believed the Catholic Church could find particular appeal because the tradition of seeking absolution for one’s mistakes or misdeeds “appeals to the Oriental,” they reported.

In the wake of the missionaries’ efforts, the Bible became a best-seller in Japan, while the number of Catholics climbed about 19 percent between 1948 and 1950, Tokumoto said.

The missionaries’ success, however, was short-lived. Relatively few of the 2,000 or so who flooded into Japan could speak Japanese, and the 1960s saw a student backlash against perceived “elite” Christians who ran several major universities.

*************************************************************************

Postscript: Even now, despite all the resources thrown at it by the West, and despite over a century of fervid Westernisation, Christians in Japan number something like 1% of the population, a percentage that ranks among the lowest in the world.

Meanwhile, a primal religion, that is to say Shinto in its nature-worshipping aspect, continues to provide a spiritual outlet for the nation as a whole. A triumph of the Sun over the Son, you could say. It gives pause for thought….

It’s the one-year anniversary of this blog, and I couldn’t have asked for a better year… There have been over 170.000 hits, far more than expected, and the positive feedback has given me the incentive to keep posting and to try and improve the content…

It’s the one-year anniversary of this blog, and I couldn’t have asked for a better year… There have been over 170.000 hits, far more than expected, and the positive feedback has given me the incentive to keep posting and to try and improve the content…