The Yoshinogari magatama expert gives instructions

The Yoshinogari theme park in northern Kyushu offers the opportunity to visitors to make a magatama stone bead. (The beads were symbols of spiritual authority in Yayoi times.) It turned out to be much easier than expected. Like much else in life, you just need good tools and preparation. Then you rub and rub and rub. It sure develops the arm muscles.

The basic process involves rubbing a soft stone against a harder one. The first step is to select the type of stone, ranging from white soap stone to the more attractive darker type which I chose to work on. You then draw a magatama shape on the stone and start rubbing it against a harder stone block in order to wear away the areas outside the drawing.

Stages of magatama making

After wearing away the corners, you’re left with the difficult bit around the ‘belly’ of the magatama. I couldn’t imagine how to approach this, but it turned out to be simplicity itself. You just use the edge of the square block to rub against.

Using the corner to get a rounded effect

After about forty minutes the magatama began to take shape. There then follows polishing down the edges, which can go on for as long as you want if you’re a perfectionist.

The final stage involves more rubbing – this time in water with a wet carbon paper to take off the small scratch marks caused by the previous rubbing. it’s worth persisting with this final stage in order to get a fine finish. Then you’re all ready to put a string through your magatama and wear it for good luck.

I took the opportunity to ask the Yoshinogari magatama makers about their interpretation of the significance. There are several theories, ranging from half a yin-yang symbol to the human embryo and basic spiral building block of the universe. The Yoshinogari consensus is rather different – they say it represents the tusk of a wild boar, a symbol of the animal’s power.

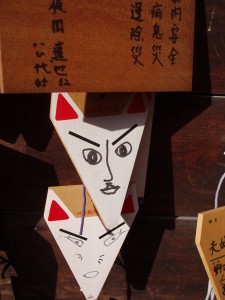

The answer might well have surprised me if I had not on the previous day visited Atago Shrine in Fukuoka. The shrine’s symbol looks like a pair of yin-yang elements, but when I asked a priest about it he told me they represented a wild boar’s tusks. So there we have it. Who ever knew that the plucky wild boar played such a part in Shinto?

Wild boar at Goo Jinja in Kyoto. Notice the fangs....

***********************************************************************************************************************

An informative page on magatama can be found on Mark Schumacher’s onmark website here. Wikipedia also has a good and even lengthier page, with seven different theories as to its significance.