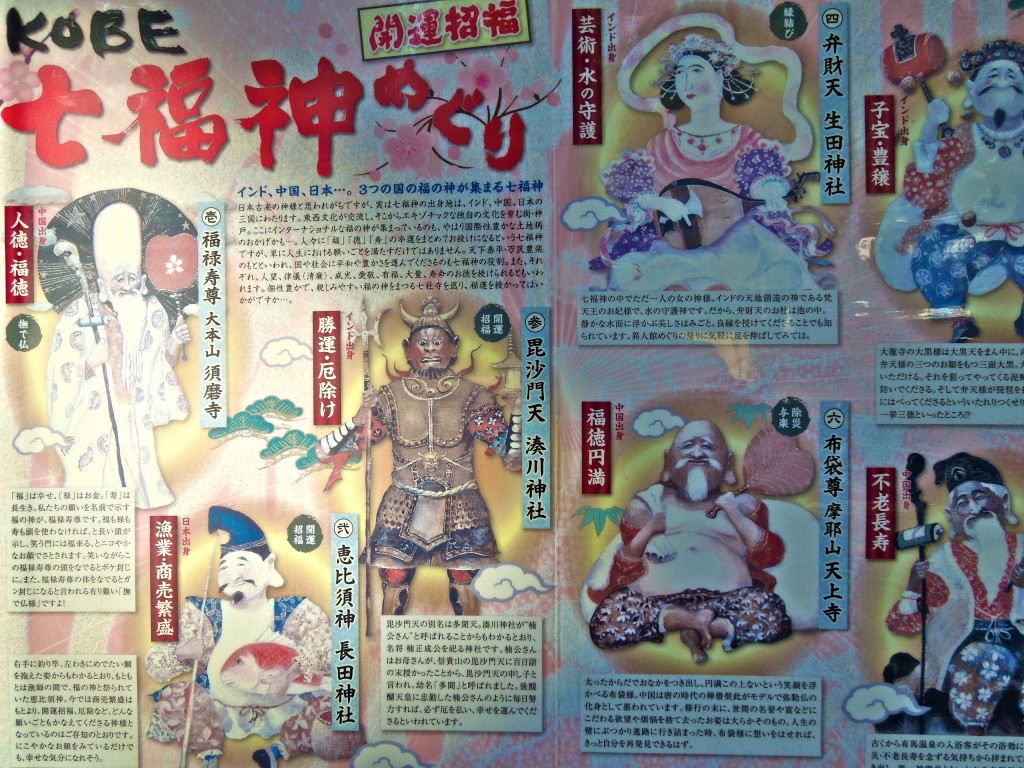

Benzaiten statue at Daikokuten Myoenji temple in Matsugasaki, Kyoto

News has arrived of the publication of a Guide to Benzaiten on Mark Schuhmacher’s website about Japanese religion. It’s a hugely impressive affair with 68 pages and 250 images from around the country, a true labour of love. Congratulations to Mark, for it’s sure to be the standard reference for anything related to this fascinating syncretic deity, muse of the arts and sole female in the Seven Lucky Gods.

*********************************************************************

Here follows an extract from the website:

Here follows an extract from the website:

In India, she [Sarasvati] was invoked in Vedic rites as the deity of music and poetry well before her introduction to China around the 4th century CE. She eventually entered Japan sometime in the 7th-8th century, where she was adopted into Japan’s Buddhist pantheon as an eight-armed weapon-wielding defender of the nation owing to her martial description in the Sutra of Golden Light. The oldest extant Japanese statue of Benzaiten is an eight-armed clay version dated to 754.

HOWEVER, the formal introduction of Esoteric Buddhism to Japan in the early 9th century stressed instead her role as a goddess of music and portrayed her as a two-armed beauty playing a lute.

Prior to the 12th century, Benzaiten’s Hindu origins as a water goddess were largely ignored in Japan. But sometime during the 11th-12th centuries, the goddess was conflated with Ugajin (the snake-bodied, human-headed Japanese kami of water, agriculture, and good fortune).

Once this occurred — once Benzaiten was “reconnected” with water — the level of her popularity changed from a trickle into a flood. By the 12th-13th centuries, she became the object of independent worship and esoteric Buddhist rites. Over time her warrior image (favored by samurai praying for battlefield success) was eclipsed by her heavenly mandala representation — even today, the two-armed biwa-playing form is the most widespread iconic depiction of Benzaiten and her standard form as one of Japan’s Seven Lucky Gods.

Once reconnected with water, she rose to great popularity as the patroness of “all things that flow” — music, art, literature, poetry, discourse, performing arts — and was also called upon to end droughts or deluges and thereby ensure bountiful harvests. Her sanctuaries are nearly always in the neighborhood of water — the sea, a river, a lake, or a pond — while her messengers and avatars are serpents and dragons. In fact, the creatures who rule the waters are all intimately associated with Benzaiten in Japan.

Eight-armed Benzaiten at Chikubushima in Lake Biwa