In prehistoric times immigrants flowed into Japan, sometimes in a trickle and sometimes in a flood. They came for the most part from Korea and China, the bulk flowing through the Korean peninsula which lay under Chinese influence. The result was that elements of Korean shamanism and Chinese folk beliefs entered Japan. The former made itself felt in miko shamanism and the rock worship that is such a striking feature of Shinto. The latter had an even more profound impact.

Rock worship – from Korea?

Chinese folk belief comprised a mixture of nature spirits and ancestor worship. It was based on a lunar/solar calendar, which was adopted in Japan, and celebratory festivals which sought to harmonise the human and spirit worlds. This was the bedrock out of which Taoism developed. It was the same bedrock out of which Shinto developed.

It’s hardly surprising then that proto-Shinto and early Taoism share much in common. Even the name. “Shin-to” (kami-way) was the Japanese equivalent of “shen-tao”, the Chinese Way of the Spirits. Kuroda Toshio, the Japanese scholar, suggested that the first usage of the word ‘Shinto’ in Nihonshoki (720) was in effect intended to signify a Japanese form of Taoism. You could say, in fact, that Shinto was the Japanese ‘Way’, in contrast to bukkyo (the teachings of Buddhism).

One mountain, many paths

Here are some traits of early Taoism, which are echoed in Shinto.

* Sacred mountains and retreat into caves

* Veneration of swords and mirrors as religious symbols.

* An intuitive response to the world

* Suspicion of words and rationality

* Lack of dogma and doctrine

* Fluid, vague and contradictory

* Appropriated by rulers to legitimise their rule

Cave worship Shinto style at Kamikura Jinja (Shingu)

Religious Daoism

Over time Taoism and Shinto developed in different directions. Taoism took off into individual transformation, the search for immortality and the aligning qi energy between the triad of heaven-human-earth. What had started off as a philosophy was turned into a religion. This was introduced to Japan in a big way in the seventh and eighth centuries after it had become established as a state religion in China.

With the import of Taoism came yin-yang ideas, the Five Phases, divination, astrology and fortune-telling techniques. In 604 Japan adopted the Chinese calendar and issued the 17 Article Constitution (17 derived from adding the largest yin number eight to the largest yang number, nine). One of the imported concepts involved the use of Tenno (Heavenly August One), to signify that a ruler had the mandate of Heaven. The title was adopted by the Chinese emperor in 674 and by his Japanese equivalent not long afterwards.

From as early as 675 Japan had a Ministry of Yin-Yang (Onmyoryo) which advised the government on affairs of state. Decisions were made according to the alignment of the stars, feng shui and complex divination techniques. Wizards of Yin-Yang (onmyoji) continued to play an influential part in the life of the ruling class. The ‘Merlin of Japan’, Abe no Seimei (921-1005), is a prime example.

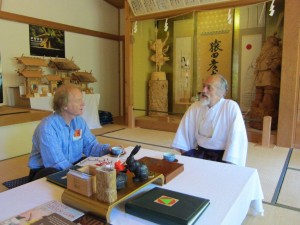

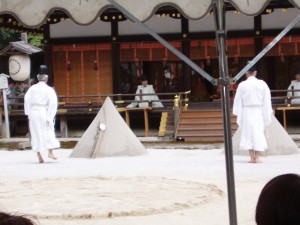

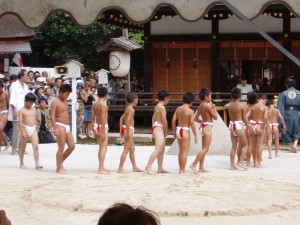

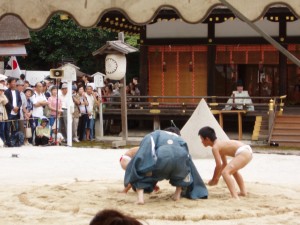

Purification rites like this derive from Taoist influence

All these developments took place while Shinto as we know it was being shaped by the ruling class. As a result the imported ideas had a huge impact. It’s reckoned, for example, that 60% of modern Shinto ritual derives from Taoist and Yin-yang practice. The purification rites, for instance. Festivals like 7-5-3 and the throwing of beans at Setsubun. Yakudoshi (years of misfortune). The veneration of swords and mirrors. The divination and fortune-telling, too. Even the very structure and naming of Shinto’s holiest shrine, Ise Jingu (jingu derives from a Taoist term for a hall of worship).

In essence, you could say that Shinto remains the closest Japan has to the ‘Way’. Shen-tao developed into Shinto. Even now, even after the Meiji reforms stripped away onmyodo and the ecstatic side of the religion, there lies a Taoist heart beneath the Confucian concern with correctness and hierarchy. It’s found in the folk practices of Shinto. It’s found above all, in the wild abandon of Shinto festivals and the cult of sacred mountains. The way of the kami may not be the Way, but it’s close.

Yin-yang symbol

Triple tomoe - Shinto symbol

(For further reading, see ‘Shinto and Taoism in early Japan’ by Tim Barrett in Shinto in History: Ways of the Kami by Mark Teeuwen (Editor) John Breen (Editor) (Author). Also Kuroda Toshi’s ‘Shinto in the history of Japanese Religion’ tr. by James C. Dobbins and Suzanne Guy which is available on JSTOR.)