People sometimes make the mistake of assuming that present-day Shinto is the way things have always been. Far from it!! Shinto has been different in every age, and you can bet it will be different again in future. And as well as variety over time, there has been great variety by region too. The standardisation of modern times dates from a wish to impose uniformity on a national state by the emerging Meiji ideologues. Before then things were far more diverse.

Coins are scattered on and around a rock in a modern Shinto shrine

Awareness of this comes when you read the accounts of Meiji era visitors to the country. One such was the American scientist, Edward Morse. An expert on molluscs, he went on a trip to Lake Chuzenji but failed to find what he was after. Instead he came across two topless girls bathing in a spring, who quickly covered up because they’d been told that Westerners found it immoral.

Following this, Morse went on to climb the 8000 ft Mt Nantai. On the summit was an ancient shrine with an open platform on which were strewn rusty coins, broken sword blades, thick strands of hair. These were offerings, and the rough way in which they were scattered reminds me of the messy nature of Okinawan altars and Siberian shaman sites. Though Morse had a scientific mindset, when he heard that most mountains in Japan had such shrines he was moved by the spiritual impulse. ‘What a wonderful conception, what devotion to their religion,’ he wrote. (It did not stop him taking some of the fragments as a souvenir, however.)

In the fascinating study of this time Mirror in the Shrine, Robert Rosenstone notes that amongst the leading kami were Inari, god of rice; Benten, goddess of the sea, Hachiman, god of warfare, Koshin, overseer of roads and highways, and Kishi-bojin, mother of demons. The first three are familiar to us today; Koshin is known, but not so much as an overseer of roads. The absentees are interesting. No Tenjin. No Amaterasu. No Okuninushi.

Offerings in Okinawa are often left scattered around after worship

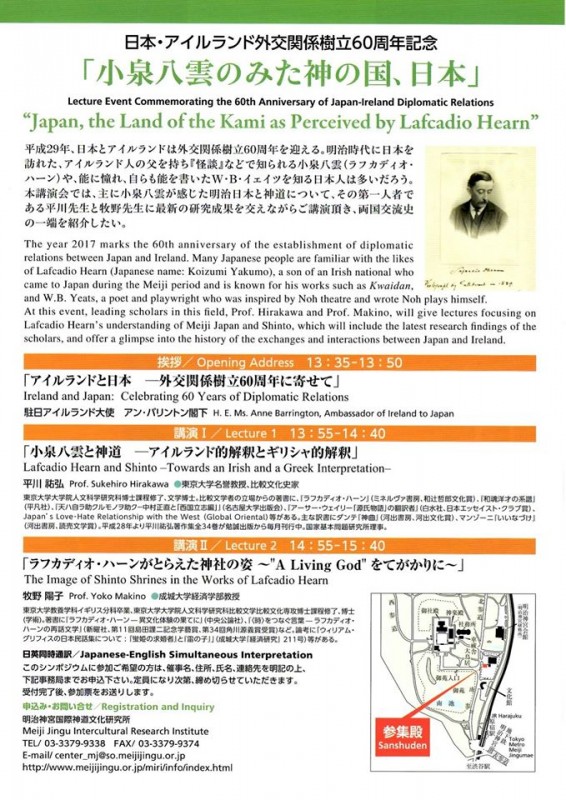

Unlike the fixed imperial hierarchy of modern times (an invention of tradition by Meiji nationalists), the kami of earlier times were liable to change, mutate, vary and manifest in different forms. For the pagan Lafcadio Hearn this was perfectly understandable as an expression of ‘The infinite Unknown’ that underlies all religions. Neat.

For Hearn it was one of the tragedies of a modernising Japan that its local deities were being lost as country folk shook off centuries of tradition. The ancient kami had for long centuries consoled the suffering of peasants and gladdened their hearts at festival time. They helped common folk cope with the great tragedy of natural disasters and human warfare. But Meiji purists insisted on ‘one shrine, one village’, and they closed down those with obscure kami while promoting those with imperial connections.

From now on the country hastened to embrace the new path of urbanisation, industrialisation and rationalisation. In the process some kami were privileged, some barely survived, and some fell by the wayside. The yaoyorazu (myriad) kami were no longer as numerous or diverse as before. In place of a demotic, localised Shinto came the state oriented Shinto of the present.

Modern offerings might not include swords or strands of hair, but they can be diverse in nature

Bawling babies face off in Japan’s ‘crying sumo’

Bawling babies face off in Japan’s ‘crying sumo’ There are many individuals who exemplify the close ties between Zen and Shinto in Japanese history, particularly in the period before an artificial line was drawn between Buddhism and ‘the indigenous religion’ in Meiji times.

There are many individuals who exemplify the close ties between Zen and Shinto in Japanese history, particularly in the period before an artificial line was drawn between Buddhism and ‘the indigenous religion’ in Meiji times.

Most people assume Ise Jingu is Japan’s oldest shrine. Mythical and archaeological evidence however says that it is Izumo Taisha. It was once the country’s most prestigious shrine, being supplanted by the propagandists of Yamato who incorporated it into the imperial mythology of the Kojiki (712).

Most people assume Ise Jingu is Japan’s oldest shrine. Mythical and archaeological evidence however says that it is Izumo Taisha. It was once the country’s most prestigious shrine, being supplanted by the propagandists of Yamato who incorporated it into the imperial mythology of the Kojiki (712).