Hearn’s beloved garden, kept as it was over a hundred years ago

Some years ago I visited Lafcadio Hearn’s house in Matsue City, which is preserved just as when he lived in it. It’s an attractive former samurai house next to the moat around Matsue Castle. The garden he described in his writing is still the same, and one can appreciate the joy he must have felt in living in such harmony and closeness with nature, in such an aesthetically pleasing setting. (You can read all about the house and garden here.}

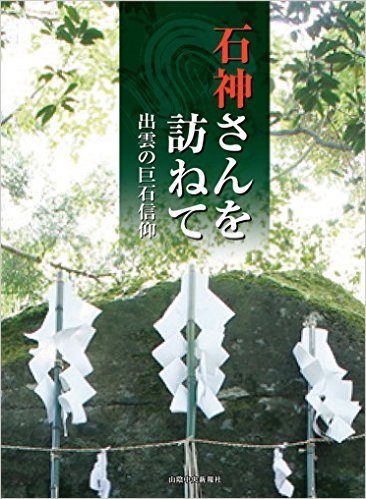

This time I wanted to explore some other places associated with Hearn to see what inspired his affinity with Shinto. Already on his journey to the Matsue area he had noticed that the region did not embrace Buddhism so tightly as other regions, meaning that it retained more of a traditional character. For Hearn it was the true Province of the Gods.

Shoko Koizumi, married to Hearn’s great grandson, at the Jozan Inari Shrine

Two of the author’s favourite shrines, Yaegaki and Kumaso, are in the countryside around Matsue, and these were reported on in an earlier post. This time I visited Hearn’s favourite Inari shrine, close to his house. Escorting me was the wife of Hearn’s great-grandson, Koizumi Shoko, and I was lucky enough to join the pair for dinner in the evening.

Hearn used to visit Jozan Inari Shrine in the castle grounds on his way to go and teach at the High School. He was particularly fond of the foxes at the shrine, especially the big stone figure in front of the shrine gate (the original is now at the Hearn Memorial Museum). In Glimpses of Unfamiliar Japan he wrote:

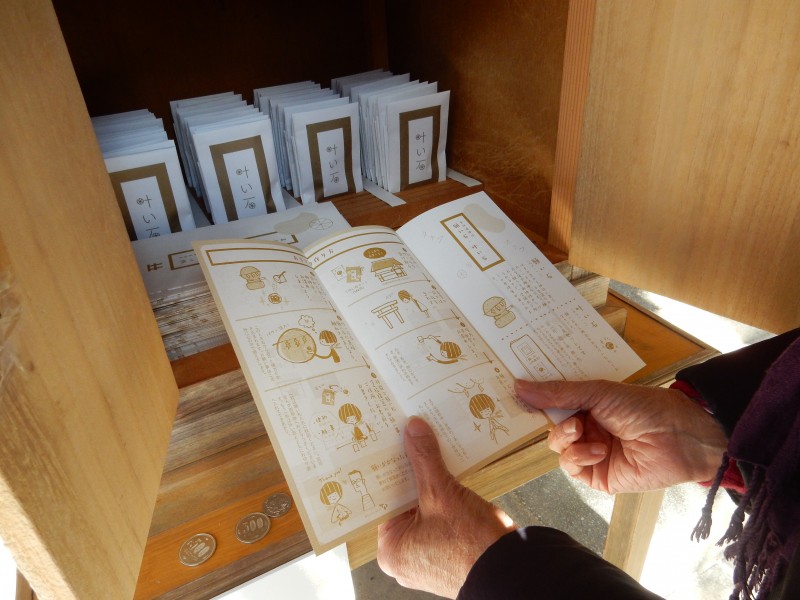

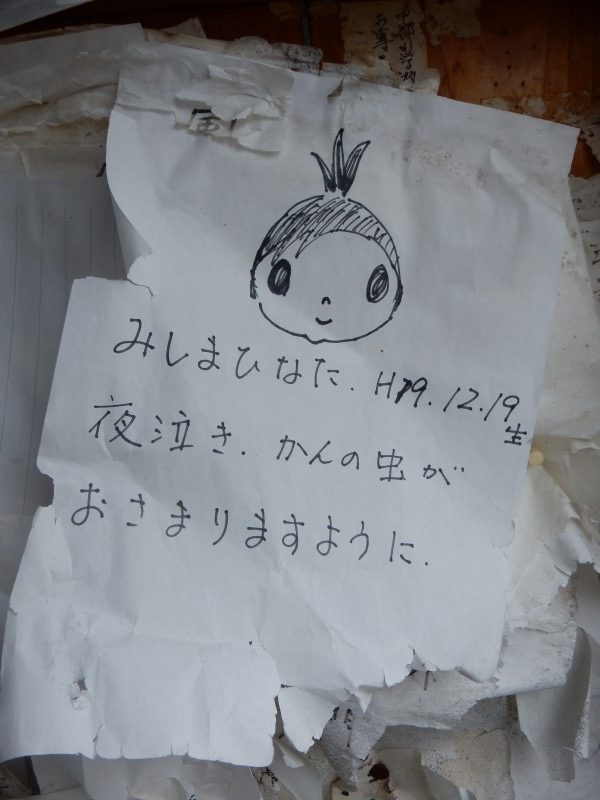

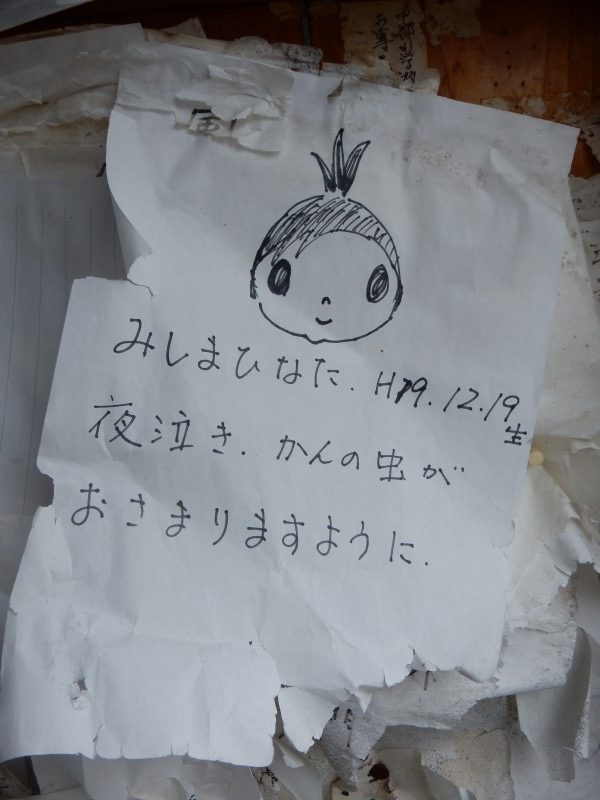

Prayer for the good health of a child not to cry at night and be plagued by ‘bugs’

Upon almost every door there is one ofuda (charm) especially particularly likely to attract the attention of a stranger. These ofuda are from the great Inari shrine of the Castle Hill and are charms against fire. They represent, indeed, the only form of assurance against fire yet known in Matsue – so far, at least, as wooden dwellings are concerned.

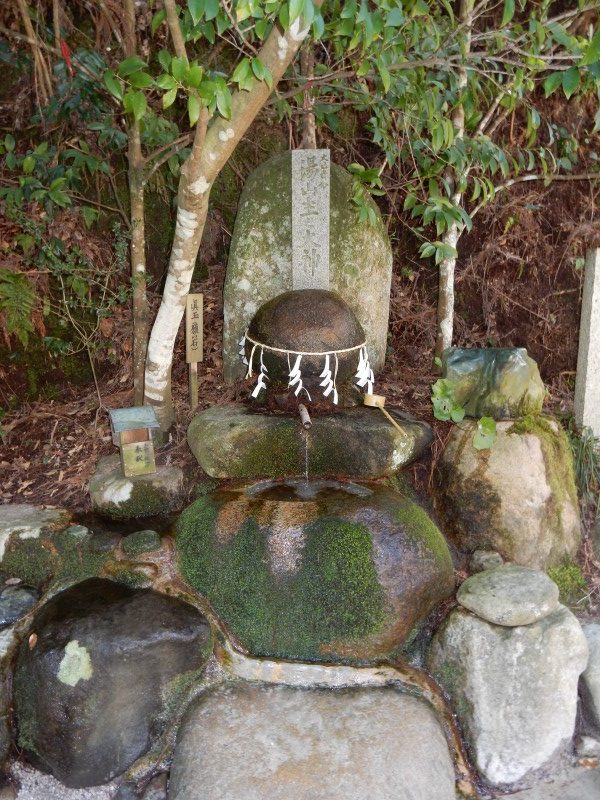

Another shrine Hearn was fond of was Komori Inari Jinja, specialist in blessings for children. He was particularly interested in the drawings and prayers that were pinned up on pieces of paper. Still today you find children playing in the yard next to the shrine and prayers from mothers displayed on the outside of the building.

The last place I’d like to mention here is a temple rather than a Shinto shrine, but typically syncretic in Edo-era style. Hearn loved it, and so did I. Gessho-ji has one of the most striking atmospheres I’ve come across in Japan, enhanced by the accompanying rain and moist surfaces. In fact Hearn loved it so much he longed to be buried there, though there was little chance of that. Gessho-ji is the burial place of the Matsudaira, the local daimyo (feudal lords),

Wandering around the graveyard I mused on the use of torii in this Pure Land temple. There’s not only the oddity of the marker of sacred space in a Buddhist sect not normally friendly to Shinto tradition, but there’s the anomaly of a Shinto symbol before a grave when every book you read says that Shinto shuns death.

The Gessho-ji cemetery for the local daimyo of Matsue, with torii standing in front of a grave

One is used to torii marking the burial mounds of imperial ancestors, given their supposedly divine descent. But daimyo? These are mere mortals, who happen to have temporal power. On the other hand, if one thinks in terms of an ancestral religion and the way that family dead become kamisama as well as buddhist hotoke. The more power a person has in this world, the more powerful their spirit after death. It’s a shamanic trait, nowhere more evident than in the great Mongol deity, Ghengis Khan.

One of the main sights of Gessho-ji is the Great Tortoise that features in a folk story and which particularly took Hearn’s fancy. Just as the ghost tales of Matsue sparked his imagination, so the giant tortoise loomed large in his fancy. Animals and insects feature prominently in his writing, and his sympathy with them was tied to a belief in the oneness of all beings.

The giant tortoise is positioned in front of the sixth Matsudaira lord, and according to tradition rubbing the its head guarantees longevity. Folklore also claims that the tortoise moves at night to drink water from the pond and wanders through the city. This fascinated Hearn, who wrote a piece about how certain artistic creations had a secret nocturnal life:

But the most unpleasant customer of all this uncanny fraternity to have encountered after dark was certainly the monster tortoise of Gesshoji temple in Matsue….This stone colossus is almost seventeen feet in length and lifts its head six feet from the ground…. Fancy…this mortuary incubus staggering abroad at midnight, and its hideous attempts to swim in the neighbouring lotus-pond!

Hearn not only had a strong attachment to animals, but was something of an animal rightist. He was vehemently opposed to hunting for recreation, and his description of the torture undergone by a terrified cow in the slaughter house of Cincinnati is stomach churning. Once when he saw a cat being tortured by the side of the road, he pulled out a pistol and shot it in the direction of the perpetrator.

‘Toads, butterflys, ants, spiders, cicadas, bamboo-sprouts, and sunsets were among Papa-san’s best friends,’ said his wife Setsuko in her Reminiscences. Based on such evidence, leading scholar Sukehiro Hirakawa wrote, ‘ I believe that the principal reason for Hearn’s appeal to the Japanese derives from Hearn’s sympathetic understanding of Japanese animism.’ The strong sense of Oneness he felt was fostered in the shrines of Matsue and the environment of his own back garden.

The tokonoma in Hearn’s house, where the objects on display are changed with the seasons. The aesthetic appeal and harmony with nature were part of why Hearn fell in love with Matsue.

It was just before March 3, Dolls Day, on the day of my visit, and the hanging scroll a male and female pair beneath plum blossom.

A window shutter in town featured the Chaplin-like drawing of Hearn when he left the US for Japan in 1890, done by a commissioned illustrator who accompanied him on the journey. Hearn soon cut his ties to the magazine that had nominally (but not financially) sponsored his trip.

Jozan Inari Jinja, near Hearn’s house, was a particular favourite of his

Hearn was particularly fond of the stone fox figures at the shrine

This guardian fox figure has an unusual shimenawa neckband

The Hearn trail around Matsue features 16 places in all, including the Kodomo no Inari Jinja (Children’s Inari Shrine), where Hearn was fascinated by the prayers pinned by mothers on the side of the shrine

Dragon detail at the entrance to Kodomo no Inari Shrine

The wonderfully atmospheric Gessho-ji, where Hearn wanted to be buried

Hearn was particularly struck by this enormous creature in the graveyard of Gessho-ji, and so was I! The giant turtle features in one of the eerie tales that feature in Glimpses of Unfamiliar Japan.

An Edo-era hand print of the famous sumo wrestler, Raiden

Hasegawa Yoko, deputy head of the Shusse Inari Shrine close to Ryusho-ji temple where Hearn went to see the splendid Jizo statues

Yomegashima was one of Hearn’s favourite sites in Matsue – small wonder given that it is dedicated to the ‘Goddess of Eloquence and Beauty’. It’s particularly alluring at sunset when deep reds and crimson spread over the far side of Lake Shinji (see Hearn’s description below).

A sculpture entitled The Open Mind of Lafcadio Hearn captures the sunset in a heart-mind shape, beautifully expressing the animist embrace of nature

Hearn’s description of Yomegashima in Lake Shinji (see above), with characteristic attention to the morbid legend concerning its name and origin:

The vapors have vanished, sharply revealing a beautiful little islet in the lake, lying scarcely half a mile away, – a low, narrow strip of of land with a Shinto shrine upon it, shadowed by giant pines; not pines like ours, but huge gnarled, shaggy, torturous shapes, vast-reaching like ancient oaks. Through a glass one can easily discern a torii, and before it two symbolic lions of stone (Kara-shishi), one with its head broken off, doubtless by its having been overturned and dashed about by heavy waves during some great storm. This islet is sacred to Benten, the Goddess of Eloquence and Beauty, wherefore it is called Ben-ten-no-shima. But it is more commonly called Yome-ga-shima, or ‘The Island of the Young Wife,’ by reason of a legend. It is said that it arose in one night, noiselessly as a dream, bearing up from the depths of the lake the body of a drowned woman who had been very lovely, very pious, and very unhappy. The people, deeming this a sign from heaven, consecrated the isle to Benten, and thereon built a shrine unto her, planted trees about it, set a torii before it, and made a rampart about it with great curiously-shaped stones; and there they buried the drowned woman.

Hearn is noted for his sensitivity and understanding of Shinto animism, but he also had a fine appreciation of the ancestral side of Shinto. This is evident in the first of his Japanese books, Glimpses of Unfamiliar Japan (1894), which contains sentiments that dovetail with my own. Indeed, I’ve written of them in previous articles though not with the same eloquence as that master wordsmith of more than a hundred years ago. (See here or here or here.)

Hearn is noted for his sensitivity and understanding of Shinto animism, but he also had a fine appreciation of the ancestral side of Shinto. This is evident in the first of his Japanese books, Glimpses of Unfamiliar Japan (1894), which contains sentiments that dovetail with my own. Indeed, I’ve written of them in previous articles though not with the same eloquence as that master wordsmith of more than a hundred years ago. (See here or here or here.)