An article in the Japan Times today by leading writer, Michael Hoffmann, tells of how the seemingly innocuous activities of prime minister Shinzo Abe mask a reactionary agenda which seeks to undo the Bunce Directive of 1945 severing Shinto’s ties with the State. Under the present administration, steps are underway toward reintroduction of the prewar situation by which Shinto was used as ideological underpinning for those in power. An alternative vision, which is taking hold overseas, is to see Shinto as a religion of the people, community based and environmentally oriented, a religion that looks to nature rather than the emperor as its guiding principle.

Prime Minister Shinzo Abe visits the Grand Shrines of Ise in Mie Prefecture on Jan. 4. (photo courtesy Kyodo)

Is Abe attempting to fuse the church and state?

Japan’s monarchy claims the oldest royal lineage in the world. The reigning Emperor is, theoretically and maybe even historically, Empress Jito’s descendant. So tangible a link to so remote a past is no doubt a factor in a deeply conservative strain in the national character.

“This year, too, the economy comes first,” declared Prime Minister Shinzo Abe on Jan. 3 in the course of his first news conference of 2017. That’s the way things are nowadays. Prose rules, not poetry. The Imperial pleasure-barge is gone. In its place, the economy. Empress Jito, her ministers and her court poets might have been shocked had they glimpsed such a future. To them, the way we live, our preoccupations, would have represented the decay into utter ruin of everything good, beautiful and sacred in life.

Ise buildings project a lush nature-loving and peaceful image

If Abe’s reaffirmed commitment to the economy would have left them cold, something else about the occasion — its venue — might have heartened them. The deep resonance of the backdrop seems almost clangorously at odds with the prosaic prime ministerial boilerplate. The Grand Shrines of Ise in Ise City, Mie Prefecture, comprise Shinto’s holiest site, dedicated to the worship of Japan’s most revered deity, the sun goddess Amaterasu — divine ancestress, mythologically speaking, of the Imperial house.

Abe’s New Year’s visit to Ise drew little comment. The Grand Shrines of Ise, unlike Tokyo’s Yasukuni Shrine, enshrine no war criminals, only gods. It’s beautifully innocent, innocently beautiful and very ancient, its founding dating back to Empress Jito’s time. So lacking is it in the dark associations that haunt Yasukuni that when Abe chose to host the Group of Seven summit in Ise last May, that also passed with little comment.

The gods and goddesses of Japanese myth are playful, child-like deities, neither awesome nor overpowering, and the Grand Shrines of Ise, with their architectural simplicity and lush natural setting, seem just what Abe said they were as he welcomed world leaders, high on whose summit agenda in May 2016 were global terrorism, global warming and similar threats to life as we know it. Ise, said Abe, is richly symbolic of “the beautiful nature and rich culture and traditions of Japan.”

Can a sinister issue be lurking here, beneath the serene surface? Sophia University religious scholar Susumu Shimazono raised that possibility in a discussion with the Asahi Shimbun earlier this month. Article 20 of Japan’s Constitution reads, in part: “The State and its organs shall refrain from religious education or any other religious activity.” The official attention Abe lavishes on the Grand Shrines of Ise may, Shimazono suspects, violate the constitutional separation of church and state.

Amaterasu, sun goddess and putative ancestor of the present emperor

Abe’s feelings regarding the Constitution are no secret. “Revising the Constitution,” he told reporters covering his party’s electoral victory in 2014, “has always been an objective since the Liberal Democratic Party was launched.” That was in 1955. The Constitution was then barely eight years old. Its roots in the postwar U.S. Occupation, and its largely American authorship, were an irritant to conservatives to whom imported notions of freedom and rights were less important than, if not inimical to, the native concept of Japan as “the land of the gods.”

As myth, the concept is charming; as fact, less so. Japanese militarism and the Pacific War show the extremes to which it can lead. Other questions aside, it seems grossly out of keeping with the modern spirit — and yet it was the great modernizing leaders of the Meiji Era (1868-1912) who drafted and enacted the Constitution of 1890, whose Article 3 gave new life amid a headlong plunge into industrialization, commercialization and (to paraphrase Abe) the economy coming first, to the “sacred and inviolable” nature of the Emperor.

Shimazono explains: “In building a modern state after the collapse of the shogunate” — the collapse, indeed, of the only world the isolated and dangerously out-of-touch early Meiji Japanese knew — “the political leadership needed a pillar around which to unify the nation. The pillar they erected was that of reverence for the Emperor” — the “sacred and inviolable” sovereign.

The postwar Constitution was intended in part as a hedge against any such idea ever again rearing its head in Japan to lead the nation into the amoral militarism whose wounds fester to this day.

“The Emperor shall be the symbol of the State and of the unity of the People,” declared Article 1, “deriving his position from the will of the people with whom resides sovereign power.” No more imperial divinity. Japan was no longer “the land of the gods.”

It was a steep demotion and not everyone was reconciled to it. Conservatives bided their time. Economic drift, coupled with increasing international hammering at Japan’s war guilt, played into their hands. Japan, they said, emasculated by a “foreign” constitution, had lost its soul. Has the time come to regain it? Is that what’s going on under cover of “the economy coming first”?

Shimazono expresses alarm at Abe’s brisk reversal of Japan’s postwar pacifism. His argument is not military but constitutional. New, hastily passed legislation permitting “collective self-defense” required a reinterpretation of war-renouncing Article 9 that many experts declare untenable. If Article 9 is vulnerable, Shimazono asks, might not Article 20, guaranteeing religious freedom and barring the state from “any religious activity,” be equally so?

This column last week discussed a package of articles in the March issue of Sapio magazine that snapped what seems a rose-tinted photograph of Japan as the best of countries, if it could only regain the lost confidence to see itself that way. One contributor called Japan “the world’s No. 1 paradise.” Another invoked the Meiji modernization as an inspiration to turn to. Meiji was indeed a confident era, and there have been few more so. It was, among other things, the era that made modern Japan a “land of the gods.” It’s more ominous than it sounds.

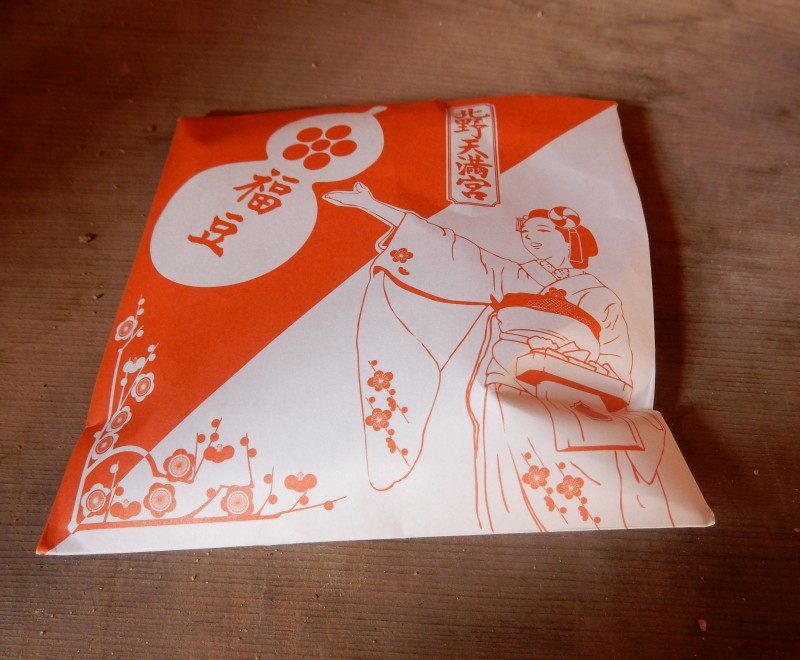

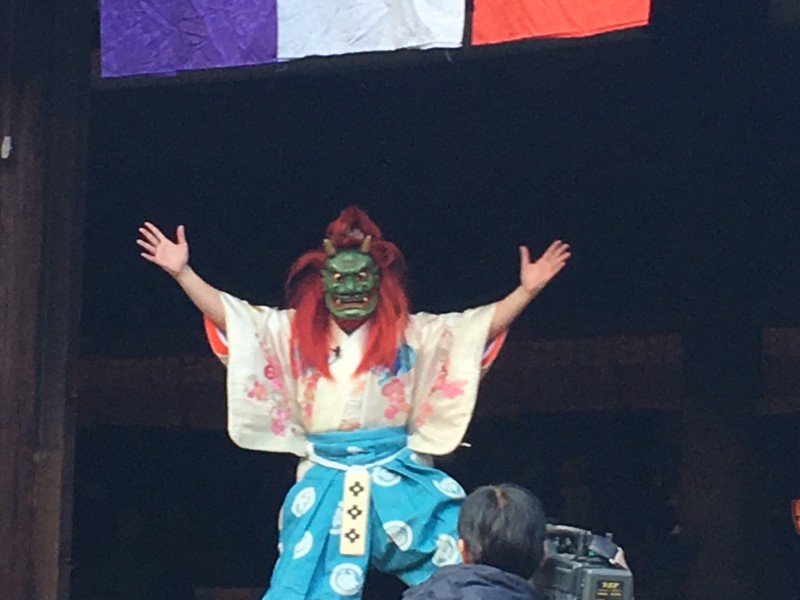

For the next two days, Japan will be celebrating the fun festival of Setsubun. Green Shinto has reported on the events in Kyoto on a number of previous occasions: see

For the next two days, Japan will be celebrating the fun festival of Setsubun. Green Shinto has reported on the events in Kyoto on a number of previous occasions: see

When Kyoto author Robert Brady decided that he had had enough of urban living, he moved out to land in the Shiga countryside with views of Lake Biwa. There was a small cabin there which could be replaced by something more substantial, and as is the way in Japan before beginning a new construction, arrangements had to be made for a ‘jichinsai’ (ground-breaking ceremony).

When Kyoto author Robert Brady decided that he had had enough of urban living, he moved out to land in the Shiga countryside with views of Lake Biwa. There was a small cabin there which could be replaced by something more substantial, and as is the way in Japan before beginning a new construction, arrangements had to be made for a ‘jichinsai’ (ground-breaking ceremony).