Shigemori’s trademark garden is this Horai recreation at Tofuku-ji, which was his first ever commission. The south-facing garden which is the official face of the Abbot’s Quarters is deliberately conventional in comparison with his other creations. More than just decorative, the garden serves religious ends. Raking the gravel is a training in mindfulness, and the Horai Isles are a mythical ideal where opposites are reconciled, presenting a lesson in Zen thinking about the underlying unity of the universe.

Green Shinto has carried several articles on the common elements between Zen and Shinto, some of which focus on rocks and the raking of sand or pebbles. The spiritual significance of rocks is another subject which the blog has covered at various times. This is all brought together in an article for the ZenVita architectural design site which deals with Shigemori Mirei, the twentieth century garden designer whose work can be found in both Zen temples and Shinto shrines. Here’s the link for the article: http://www.zenvita.com/blog/shigemori-mirei-and-the-power-of-rock.html

And here’s how the article begins…

Shigemori’s checkerboard pattern of moss and stone slabs echoes the Japanese aesthetic of ‘mikansei’, or incompleteness, as it fades away into the ‘borrowed scenery’ of a nearby grove of trees.

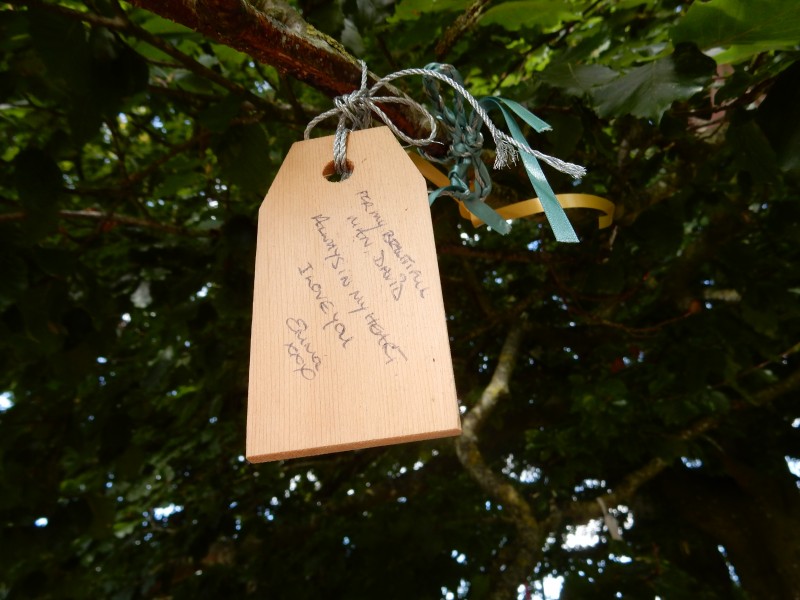

Rocks in Japan have long been seen as sacred. In Shinto there are ‘spirit-bodies’ made of rock which form the object of worship, the idea being that ancestral spirits descend into them and are made manifest. These special rocks, known as iwakura, are hung with rice rope and treated with reverence. In Buddhism too rocks are revered, and all over Japan are bibbed stones representing Jizo, guardian of the dead.

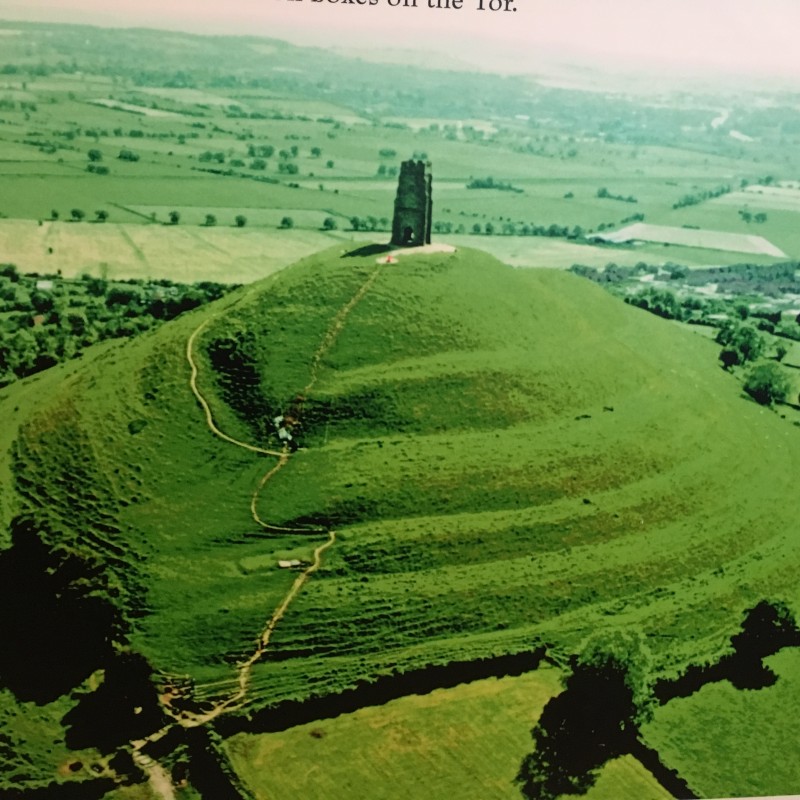

The association with the dead is typical of an animist universe in which rocks represent continuity, in contrast to the transient world of vegetation. The desire for life after death means that the human spirit is associated with the former, the human body with the latter. The connections were reinforced by ancient burial patterns, when bodies were sealed in tombs (or left on hillsides). While the body decayed, the spirit was absorbed into the rock.

Some see these numinous rocks as the origin of Japanese gardens, for they were marked off as distinct from the surrounding nature. The ground around them may have been cleared, and as time passed other rocks were added and arranged in groups. The placement was done with care, for these were the seat of spirits. As Alan Watts pointed out, rocks are not dead and inorganic but foster life, the supreme example being the large rock on which we hurtle through space and which ‘peopled’ us into existence. ‘Where there are rocks, watch out!’ said Watts.

One person very much aware of the potency of rocks was the twentieth-century garden designer, Shigemori Mirei ((1896-1975). He was a follower of Shinto, and the house in which he lived near Kyoto University had belonged to a line of priests from nearby Yoshida Jinja. ‘Nature is a world made by the gods,’ he once wrote, and in an essay on the Japanese garden he identified nature worship as the source. Interestingly, his trademark feature is standing stones.

(to read more, please click here to see the full and original ZenVita posting.)

A recreation of mythical Mt Sumeru at the centre of the cosmos. But what is the significance of a rock being at the centre of the universe? A possible answer is suggested in the article…

A book on Japanese Culture written by an academic and subtitled ‘The Religious and Philosophical Foundations’ hardly promises to be light reading. Yet this relatively slim volume (154 pages), while not exactly a bundle of laughs, is clear, accessible and informative. Indeed, one could go further and say that it’s one of the shortest yet authoritative overviews in print. ‘A well-rounded, succinct, and thought-provoking analysis’ says Alex Kerr.

A book on Japanese Culture written by an academic and subtitled ‘The Religious and Philosophical Foundations’ hardly promises to be light reading. Yet this relatively slim volume (154 pages), while not exactly a bundle of laughs, is clear, accessible and informative. Indeed, one could go further and say that it’s one of the shortest yet authoritative overviews in print. ‘A well-rounded, succinct, and thought-provoking analysis’ says Alex Kerr.