The news this morning that prime minister Abe Shinzo’s political allies have won a two-thirds majority in the Upper House elections does not bode well for the future direction of Japan. Or Shinto… (The article below is a truncated version of the original.)

For a youtube video (6 mins) exposing the group’s growing influence, see here.

*********

The Religious Cult Secretly Running Japan

by Jake Adelstein and Mari Yamamoto in The Daily Beast July 10, 2016

Nippon Kaigi, a small cult with some of the country’s most powerful people, aims to return Japan to pre-WWII imperial “glory.” Sunday’s elections may further its goal.

Nippon Kaigi, a small cult with some of the country’s most powerful people, aims to return Japan to pre-WWII imperial “glory.” Sunday’s elections may further its goal.

TOKYO — In the Land of the Rising Sun, a conservative Shinto cult dating back to the 1970s, which includes Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe and many of his cabinet among its adherents, finally has been dragged out of the shadows.

The group is called Nippon Kaigi (Japan Conference) and is ostensibly run by Tadae Takubo, a former journalist turned political scientist. It only has 38,000 members, but like many an exclusive club, or sect, it wields tremendous political influence.

Broadly speaking, Shinto is a polytheistic and animist religion native to Japan. The state-sponsored Shintoism promulgated here before and during World War II also elevated the Emperor to the status of a God and insisted that the Japanese were a divine race –– the Yamato; with all other races considered inferior.

Nippon Kaigi originally began in the early 1970s from a liberal Shinto group known as Seicho No Ie. In 1974, a splinter section of the group joined forces with Nippon o Mamoru Kai, a State-Shinto revival organization that espoused patriotism and a return to imperial worship. The group in its current state was officially formed in May of 1997, when Nippon o Mamoru Kai and a group of right-leaning intellectuals joined forces.

The current cult’s goals: gut Japan’s post-war pacifist constitution, end sexual equality, get rid of foreigners, void pesky “human rights” laws, and return Japan to its Imperial Glory. With Japan’s parliamentary elections to be held on July 10, the cult may now have its chance to dominate politics completely. If the ruling coalition wins enough seats, the door will open to amending Japan’s modern democratic constitution, something that has remained sacred and inviolate since 1947.

Prime minister Abe on his controversial visit to Yasukuni Jinja (courtesy Japan Times)

Indeed, for Japan, these elections may be a constitutional Brexit—deciding whether this country moves forward as a democracy or literally takes a step back to the Meiji era that ended more than a century ago. Then, the Emperor was supreme and freedom of expression was subservient to the interests of the state.

The influence of Nippon Kaigi may be hard for an American to understand on a gut level. But try this: Imagine if “future World President” Donald Trump belonged to a right-wing evangelical group, let’s call it “USA Conference,” that advocated a return to monarchy, the expulsion of immigrants, the revoking of equal rights for women, restrictions on freedom of speech—and most of his pre-selected political appointees were from the same group.

Abe, a third-generation politician, is the grandson of Nobusuke Kishi, who was Japan’s minister of munitions during WWII and arrested as a war criminal in 1945 before becoming prime minister in the 1950s. Abe is a staunch nationalist and historical revisionist, who also served as prime minister, from 2006 until 2007, before resigning abruptly mid-term. His ties to the Nippon Kaigi organization go back to the ‘90s.

The Asahi Shimbun and the independent press in Japan have called this year’s campaign “The Hidden Agenda Elections.” Local media have reported that the LDP and partner political parties have made sure their candidates avoid mentioning constitutional revision in their stump speeches.

The ideology behind Prime Minister Abe and his cabinet had received only modest scrutiny from Japan’s mainstream media until this May. All that changed with the publication of the surprise best seller, Nippon Kaigi No Kenkyu (Research into Japan Conference) by former white-collar worker turned journalist, Tamotsu Sugano, on April 30.

Japan’s leading constitutional expert, Setsu Kobayashi, who is also a former member of Nippon Kaigi, says of the group, “They have trouble accepting the reality that Japan lost the war” and that they wish to restore the Meiji era constitution. Some members are descendants of the people who started the war, he notes.

Despite Nippon Kaigi’s small numbers overall, half of the Abe Cabinet belongs to the Nippon Kaigi ‘National Lawmakers Friendship Association’, the group’s political offshoot. Prime Minister Abe himself is the special advisor. Former Defense Minister Yuriko Koike, who is running for Governor of Tokyo, is another prominent memberSankei Shimbun and others have reported that Nippon Kaigi even tried to pressure the publisher, Fusosha, into dropping the book on April 28.

The protest letter sent to the publisher was surprisingly under the name of the group’s secretary general, Yuzo Kabushima, not the name of the Chairman Tadae Takubo. Kabushima is a staunch Emperor worshipper and was a key member of Seicho No Ie’s student movement. (Sugano argues in his book that Kabushima is the person really running the organization.

Under prime minister Abe Shinzo, nationalist groups have been emboldened, such as this paramilitary group worshipping legendary first emperor, Jimmu, at Kashihara Jingu.

Despite the threatening tone of the letter, the publisher didn’t budge. Originally, only 8,000 copies of the book were printed. It’s now on it’s fourth printing with over 126,000 copies sold. Five other books have now been printed on the group; magazines are running front-page stories about them.

Suddenly, Nippon Kaigi is very visible. Sugano is surprised and relieved to see Nippon Kaigi and its influence on national policy finally getting attention. He himself is a political conservative who graduated from the University of Texas with a degree in political science before returning to Japan over a decade ago. While he was living in Texas, where he picked up a bit of an accent, he noticed how the Christian evangelical movement exerted political influence and sees some parallels in their methods and those of Nippon Kaigi.

Sugano was still a white collar worker aka “salary-man” when he first became aware of the existence of Nippon Kaigi. Back in 2008, Sugano recalls the shift he felt in the atmosphere on the streets. “Crazy people were starting to speak out,” he says. Protests lead by groups, such as the anti-foreigner hate speech group Zaitokukai were more noticeable. He saw an ugly escalation of their activities with each passing day.

He found these hate speech movements troubling and started to infiltrate their protests, documenting the events in photos and recordings. In order to understand the motives of members and supporters, he started to dig into the conservative publications often referenced in their online comments.

Nippon Kaigi flags at Yasukuni Jinja

The contributors that wrote for these publications puzzled him. Many were established in their field, journalists and academics, all contributing on topics unrelated to their expertise. This peculiar pattern helped him connect the dots: they all seemed to be members of one group. That realization led him down the rabbit hole, where he found the revisionist wonderland that is Nippon Kaigi.

Nippon Kaigi, he found, used neto-uyo (cyber right wingers who troll anyone on the internet they feel writes negatively of Japan), intellectuals, politicians, and closet sympathizers in mainstream media to exert considerable influence on policy and public opinion.

That included getting the Japanese government to reinstitute the Imperial Calendar, which was banished by the U.S. occupation government. It’s 2016 in the West, but under the Imperial Calendar, based on the reign of the Emperor, it is year 28 of the Heisei era. The system is so confusing that many reporters in Japan carry a handy chart to translate the Imperial Calendar dates into Western time.

While several recently published books and articles paint a picture of a masterful Machiavellian organization that has skirted the law to avoid having to register as a political group, Sugano believes they are primarily reactionary with no clear idea what they want to do once their goals are achieved.

“They have worked steadily and stealthily with local politicians and political lobbies to oppose things like gender equality, recognition of war crimes and the comfort women [sex slaves during WWII], women using their maiden names after marriage etc. It’s anti-this and anti-that but has no vision of the future.”

********************

From Japan Today on July 14, 2016, by Mari Yamaguchi

Founded in 1997, Nippon Kaigi has strived to revise the constitution to restore traditional gender roles, increase imperial worshipping and put public interest before individuals. The group is believed to be behind Abe’s comeback in 2012 and has become increasingly influential.

Their grass-roots movement backed by Shinto shrines and other new religious groups has a growing membership that reportedly includes many of Abe’s Cabinet ministers and hundreds of national and local lawmakers.

The organization holds lectures and other events to spread its views and defends Japan’s wartime atrocities while accusing China and South Korea of lying or exaggerating their suffering. It also believes the U.S. postwar occupation brainwashed Japanese with guilt and that education since the war was self-degrading.

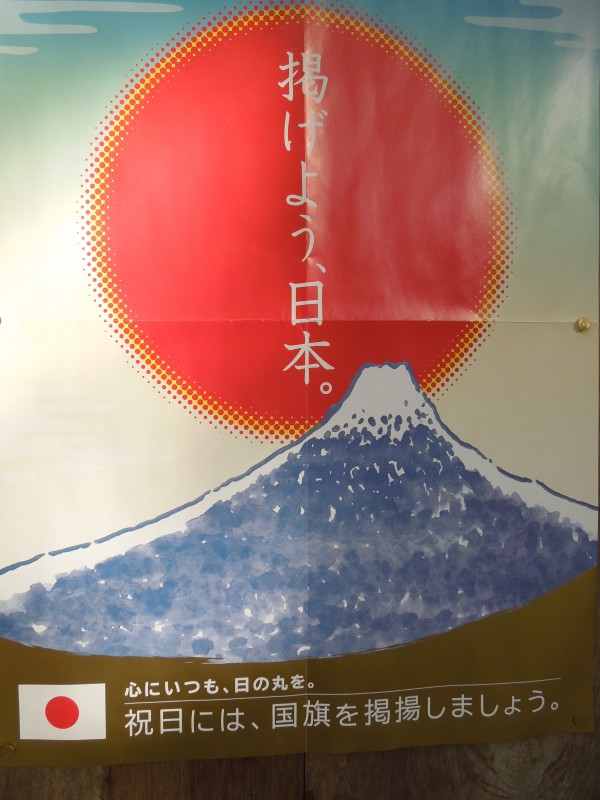

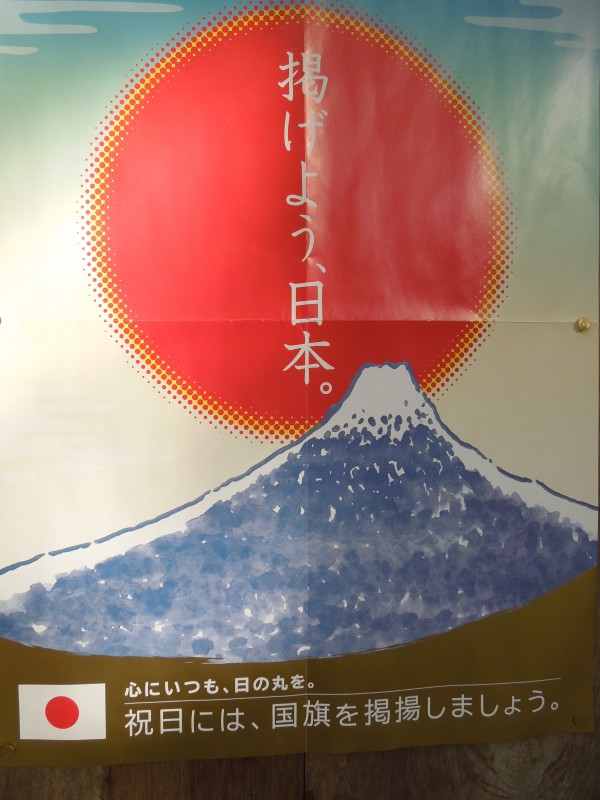

Always keep the rising sun in your heart, says a poster put out by Jinja Honcho

*********************

From the Japan Times article, ‘For Abe it will always be about the Constitution’ by Debito Arudou July 31, 2016

For decades Abe and his minions at the ultranationalist Nippon Kaigi (Japan Conference) lobby group (of which most of Abe’s Cabinet are members) have made no secret that their primary goal is to make Japan “autonomous.” To restore Japan to an imagined state of glory based upon blood nationalism, returning power to a bred elite, reviving Japan’s military political power with a seat at the civilian policymaking table, and putting the duty on the people to follow the state, not the other way around.

That has always meant getting rid of that pesky American-written and “imposed” postwar “peace Constitution” that enshrines allegedly “Western” values of human rights and empowerment of the individual. No longer content to ignore the Constitution, Abe wants to scrap it.

*******************

Related articles

- Jeff Kingston, “Nationalism in the Abe Era”

- Adam Lebowitz and Tawara Yoshifumi. “The Hearts of Children: Morality, Patriotism, and the New Curricular Guidelines.”

- David McNeill, “Nippon Kaigi and the Radical Conservative Project to Take Back Japan.”

- Sachie Mizohata, “Nippon Kaigi: Empire, Contradiction, and Japan’s Future.”

- Mark R. Mullins, “Neonationalism, Religion, and Patriotic Education in Post-disaster Japan.”

- Nakano Koichi, “Contemporary Political Dynamics of Japanese Nationalism.”

- Karoline Postel-Vinay, “The Global Rightist Turn, Nationalism and Japan.”

- Lawrence Repeta, “Japan’s Democracy at Risk – The LDP’s Ten Most Dangerous Proposals for Constitutional Change“

- Sven Saalar, “Nationalism and History in Comporary Japan.”

- Sasagase Yuji, Hayashi Keita and Sato Kei. “Japan’s Largest Rightwing Organization: An Introduction to Nippon Kaigi.”

- Akiko Takenaka, “Japanese Memories of the Asia-Pacific War: Analyzing the Revisionist Turn Post-1995.”

- Tawara Yoshifumi. “The Abe Government and the Screening of Japanese Junior High School Textbooks 2014.”

Nippon Kaigi, a small cult with some of the country’s most powerful people, aims to return Japan to pre-WWII imperial “glory.” Sunday’s elections may further its goal.

Nippon Kaigi, a small cult with some of the country’s most powerful people, aims to return Japan to pre-WWII imperial “glory.” Sunday’s elections may further its goal.