Izanagi and Izanami, the Adam and Eve of Japan?

My attention was caught recently by an article in the conservative leaning Daily Yomiuri by a Japanese professor at Waseda University. It asked the question about when the Japanese became Japanese. The answer he gave, interestingly, is constructed by myth.

The assertion that the Kojiki and Nihongi were ‘artificial myths’ collected as part of a nation-building policy by the Yamato clan is hardly new. Nor is the claim that they served to legitimise the emperor and keep the ruling family in power. However, the idea that Ookuninushi was originally the main Yamato deity rather than an Izumo god is an interesting viewpoint, which effectively torpedoes the notion of Amaterasu having been the imperial ancestor since ancient times.

The professor’s theory suggests that after an Izumo ruler called Ohonamochi ceded his country to the Yamato, the people of Izumo began to worship the Yamato deity, Okuninushi (the main kami at Izumo Taisha). The rulers of Yamato subsequently invented a new myth for themselves, that of descent from Amaterasu.

It’s an intriguing assertion and might be considered radical for a conservative paper. However, there is one key sentence worth noting in what the professor says… “the artificial national myth preserves the traces of myths that had been passed down from older generations around the Japanese islands.”

Those older local myths are the ones the common people lived by before the artificial national myth was constructed. It is there that folk Shinto, as opposed to imperial Shinto, has its roots. It is in those older local myths that I believe the true heart of Japan resides.

********************

Myth of Kojiki: When Did We Become Japanese?

Naoki Matsumoto

Professor, Faculty of Education and Integrated Arts and Sciences, Waseda University

Introduction

According to its preface, the Kojiki was completed in 712 A.D. What did the creation of Kojiki mean to the Japanese islands? I will reconsider this question through the myth shown in its first volume.

O no Yasumaro, the man who compiled the Kojiki (Muromachi Period statue, pic by Michael Lambe)

The Kojiki (in 3 volumes) and the Nihon Shoki (in 30 volumes, completed in 720) are the national histories of the Yamato dynasty whose compilation was allegedly ordered by Emperor Temmu, who ascended to the throne in 672. There seem to be two background factors behind the issuance of those national histories from the late 7th century to the early 8th century: the position of the Yamato dynasty in the East Asian world, and domestic politics.

Simply put, the issuance was part of the process of recognizing their own national identity and declaring it both domestically and internationally. It was a time when new nation building was in progress by declaring independence from the vassal relationship with China, adopting their own era names starting from Taika, the country name Nippon and the title name Tenno (Emperor), and establishing their own legal system, called Ritsuryo, based on the law of an old Chinese dynasty called Tang. Those who seek to build a new nation need to establish a national history that explains their own origin and legitimacy, and this should be a matter of common sense throughout the world.

Why do Kojiki and Nihon Shoki incorporate myths?

The first volume of Kojiki and the first and second volumes of Nihon Shoki describe Kamuyo, or the time of gods. This part is generally called Kiki Shinwa (the myths of Kojiki and Nihon Shoki) or Shindaishi (a history of the time of gods).

From the creation of the universe to Izanaki and Izanami creating a new country, the supreme goddess Amaterasu hiding inside a rock hut, Susanowo exterminating a monster serpent, Ookuninushi-no-Mikoto building a new country and handing it over to the descendants of gods, the descendants of gods falling onto the country, and the birth of the first emperor Jinmu, this part is organized in the form of a history progressing in chronological order. In so doing, it explains the origin and legitimacy of the Yamato dynasty.

This is, to put it very briefly, an artificial myth of extremely political nature stating that the power of the great goddess Amaterasu was vital to the world and this is the reason why her descendants had to descend to the country to be its king (in order to differentiate traditional folk myths and intentionally created myths, we will call the latter myths).

Why, incidentally, did both Kojiki and Nihon Shoki place this long Kamuyo part before the first emperor, instead of starting the history from him? In the past, there were a number of small village communities around the Japanese islands. Each community had its own myth narrating the origin of the village, and the myths worked as a social rule to maintain the community.

For such communities, the myths were past facts that undoubtedly existed with the ability to shape everything from the life and death of the people, to what the society looked like. Therefore, even if these types of myths look similar to other sorts of fiction, their nature is fundamentally different from stories that are told in the past tense and the indirect form such as “I heard that there was a man in the past” or old tales that do not specify a location like “once upon a time, in a certain place.” I believe that the Yamato dynasty attempted to claim their origin and legitimacy by taking advantage of the power of myths.

The back of the 26th leaf,

Kojiki, Vol. 1, the

Kan’ei version (owned by the author)

The third to sixth lines describe that

Ookuninushi-no-Mikoto had five names in total. After this part, this god overcomes numerous hardships to become literally

Ookuninushi, or the great master of the country.

The cover of Kojiki, Vol. 1, the Kan’ei version (owned by the author)

Published in 1644. The basic text of Kojiki in the early modern age. Kada no Azumamaro and Kamo no Mabuchi also learnt Kojiki with this text.

How to create a new myth: Ookuninushi-no-Mikoto, etc.

In the myth of Kojiki and Nihon Shoki, many gods that the people and clans around the country believed in appear, including Susanowo, Ohonamuchi, and other gods in the area of the Izumo myth. According to Kojiki and Nihon Shoki, Ohonamuchi is another name for the well-known Ookuninushi-no-Mikoto. Curiously enough, Ookuninushi-no-Mikoto only appears in Kojiki, Nihon Shoki, and books that are apparently under their influence. I consider that he was probably a god created by the Yamato dynasty and originally did not exist in Izumo.

Kojiki says that Ookuninushi-no-Mikoto had four other names, and Nihon Shoki mentions his six bynames. As the name of a god represents the character or function of the god in question, each byname means a god who was originally a distinct one. In other words, the myth of the Yamato dynasty consolidated multiple individual gods to craft a single god under the name of the great country master.

This god claimed the legitimacy of the Yamato dynasty for their control over this land by holding that the god handed over the country to the descendant of gods as a stable country master. But even so, why was the legitimacy explained in such a complicated manner? It is obviously a roundabout way in terms of the subject of the myth that “the power of Amaterasu was., so her descendants did.,” as mentioned above. Why was Amaterasu not made the one and absolute god to undertake the whole process to the establishment of the nation?

The answer is that such a roundabout way was a means of managing to establish Shindaishi as a myth. Suppose that you wrote a new myth from scratch. How persuasive could it be? Who would be convinced by facing, one day almost suddenly, a myth that is only full of strange stories with gods that people believe from generation to generation found nowhere in those stories, and being told that this is the national myth of the Yamato dynasty and you must live according to it from this day forward? If myths had no power, it would be meaningless for Kojiki and Nihon Shoki to incorporate myths. This was why those histories needed to have local gods.

People can only believe in myths if they contain gods that they have believed in and stories that they have heard from the old people in their village. The Yamato dynasty probably created the myth of the nation as a quasi-community by leveraging local faith and myths to maintain the power of myth that defines how a community should be. Viewed from the reverse angle, it means that the artificial national myth preserves the traces of myths that had been passed down from older generations around the Japanese islands.

Inasa no Obama, or the Little Beach of Inasa (photo by the author)

Ookuninushi-no-Mikoto allegedly swore to hand over the country at this place, just near the Izumo Taisha shrine, Izumo City, Shimane Prefecture.

Conclusion

Myths represent the ideology of the people who believe them. A variety of myths that existed around the Japanese islands were gathered to create the myth as a national ideology, and this myth in turn spread around the islands gradually. The Records of Izumo Province [Izumo-no-kuni Fudoki] established in 733, for example, describes Ohonamochi handing over the country to the descendants of gods, and the Izumo Taisha shrine started deifying Ookuninushi-no-Mikoto sometime later. This means that Izumo embraced the myth of the Yamato dynasty. Izumo became Japan, and the people in Izumo became Japanese at this point.

It is not easy to answer the questions of what Japan is and when the Japanese culture started to exist, but I suppose that the ancient myth and myths imply a clue to solve them.

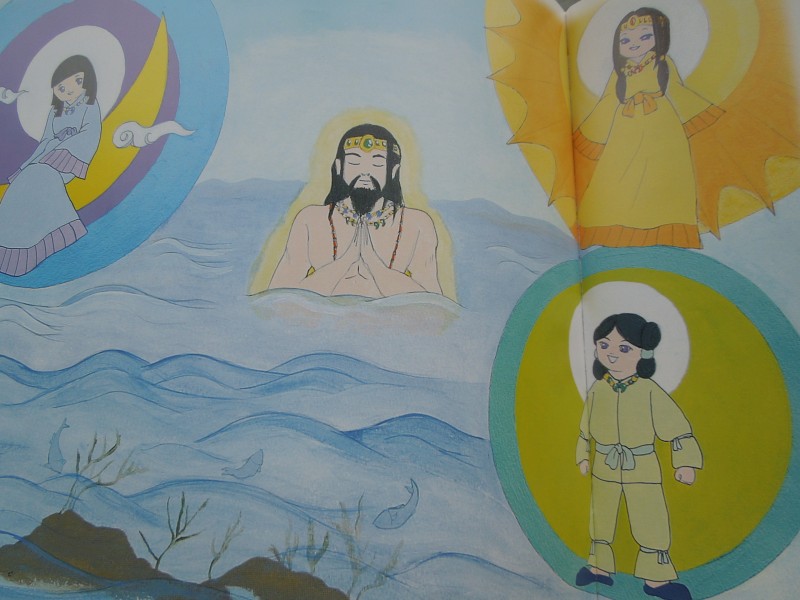

Okuninushi, perhaps the true maker of the land of Japan, here featured in the tale of the hare of Inaba.

In 2012, to celebrate the 1200th anniversary of Kojiki (712), NHK commissioned a version of the Hyuga cycle of myths, central to the putative descent of the imperial line from heaven.

In 2012, to celebrate the 1200th anniversary of Kojiki (712), NHK commissioned a version of the Hyuga cycle of myths, central to the putative descent of the imperial line from heaven.

The back of the 26th leaf, Kojiki, Vol. 1, the Kan’ei version (owned by the author)

The back of the 26th leaf, Kojiki, Vol. 1, the Kan’ei version (owned by the author)