Buddhist gateway that opens onto a torii standing astride a path leading to Tosho-gu, a shrine dedicated to the spirit of Tokugawa Ieyasu

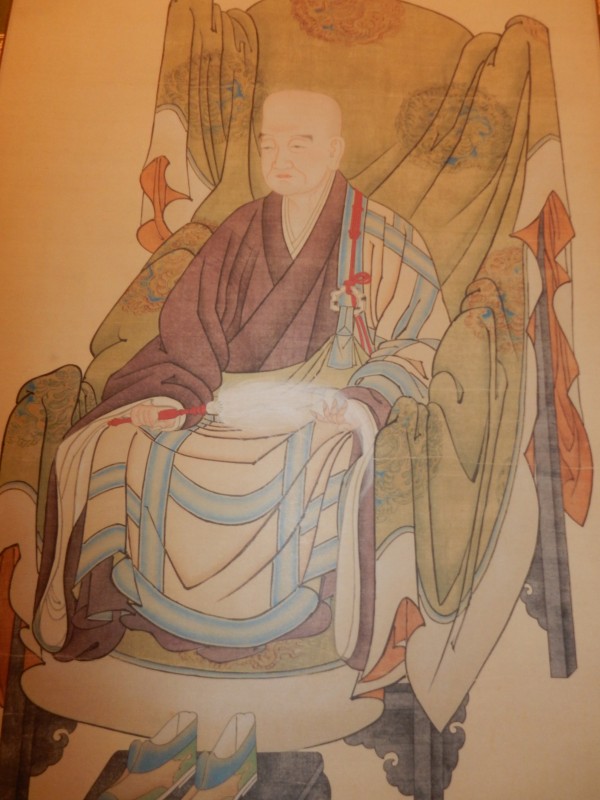

Konchi-in is a subtemple of the Nanzen-ji monastery and one of Kyoto’s gems. It packs a great deal into a compact space – garden and teahouse by master designer, Kobori Enshu; celebrated artwork; a mausoleum for Tokugawa Ieyasu. The temple’s buildings date back to 1605, when it was relocated and extensively restored by Nanzen-ji’s influential abbot Ishin Suden (1569-1633). Known as ‘the black pope’, he was a close advisor to the first three Tokugawa shoguns and chose Kobori Enshu to lay out the garden in expectation of a shogunal visit which never actually took place.

In terms of Shinto, the subtemple is notable for having two shrines, one animist and one ancestral. The animist shrine is a small affair on a pond island dedicated to Benten-sama. Often associated with water, she rules over the spirit of place and a large torii marks the entrance to her shrine.

The front of the Tosho-gu with its Buddhist roof

On the slope above the garden a grand entrance gate leads directly to the Tosho-gu shrine. This is a branch of the famous Nikko shrine dedicated to the spirit of Tokugawa Ieyasu. It was at the behest of his grandson, Iemitsu, who saw deification of Ieyasu as a means of cementing the ruling dynasty in the national consciousness. In the Edo period there were some 500 branch shrines, but the anti-Tokugawa Meiji government drastically reduced their number to the present 130.

Tosho-gu shrines are usually bright and ornate, but this one looks decidedly run down. Inside is a statue of Ieyasu, and across the front beam are pictures of shoguns. But the most interesting feature is the architecture, for the front building is built like a temple with tiled roof whereas the back of the building is decidedly Shinto in style with a bark roof.

The back of the temple is decidedly Shinto in style by contrast with the Buddhist roof to which it is attached

Gardens are something to which both Shinto and Buddhism have contributed, and in their representations of nature they have an obvious appeal. The celebrated ‘turtle-crane garden’ at Konchi-in is particularly interesting because though it is Buddhist in conception, it honours a Shinto kami. (Turtles were a symbol of longevity and cranes a symbol of good fortune.)

Beautiful in itself, the garden can be read in symbolic terms as an homage to Ieyasu. In the foreground is a sea of raked gravel, behind which are rock-islands set against a verdant backing of vegetation. Between the turtle island (flatter, to the left) and the crane island (taller, to the right) is a long flat ‘altar stone’ facing up towards the Tosho-gu shrine in the top right, once visible but now screened by trees. The grouping of rocks in the middle symbolising the mythic Horai Isles of the Blessed would thus by inference have included the spirit of Ieyasu enshrined above. (The illustration below names the salient features of the garden.)

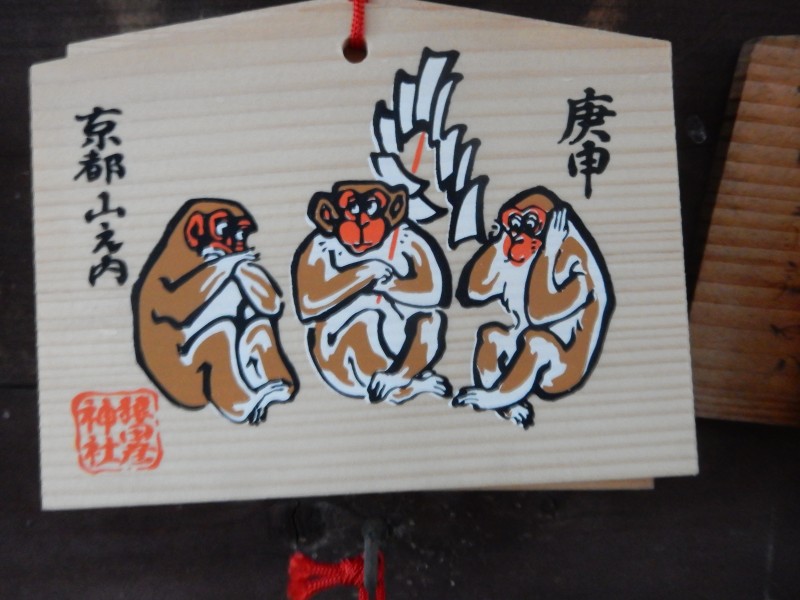

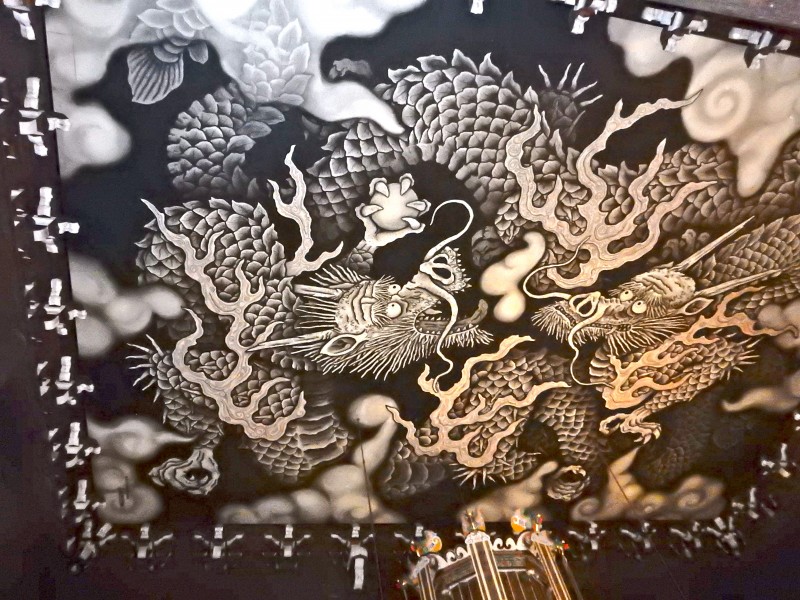

It’s the year of the monkey, which makes it a particularly apt time to visit the subtemple because of the celebrated fusuma-e painting by Hasegawa Tohoku that it houses (see below). It shows a monkey reaching out to grasp a reflection of the moon reflected in the pond below. It’s a telling Buddhist parable about chasing after illusion.

It’s the year of the monkey, which makes it a particularly apt time to visit the subtemple because of the celebrated fusuma-e painting by Hasegawa Tohoku that it houses (see below). It shows a monkey reaching out to grasp a reflection of the moon reflected in the pond below. It’s a telling Buddhist parable about chasing after illusion.

Opposite the subtemple is an enormous patch of land which is being developed by Larry Ellison (of Oracle fame), the fifth-richest man in the world (!). It used to be an estate belonging to an early twentieth-century film magnate and politician, with a garden by the famed designer, Ogawa Jihei, and a special entrance was made for a visit by Emperor Meiji. Now the site is filled with construction cranes and word has it that the Kyoto-loving Ellison is building a second house there, though interestingly in the Zen cemetery which abuts the estate stands a large torii. One wonders what his guests will think of that as they look out of their bedroom windows at night…

The torii in the Zen cemetery of Nanzen-ji, right next to Larry Ellison’s estate. The stone markers with triangular tops are apparently for those who died fighting for the emperor in WW2.

Monkey reaching for the moon by Hasegawa Tohoku. The ‘direct experience of life’ is something common to both Zen and Shinto.

The small shrine of Sarutahiko Jinja is not very well known and its set in the north-west in an unprepossessing part of Kyoto, sadly surrounded by some of the city’s uglier urban conglomeration. Nonetheless it possesses one of the most striking features in this year of the monkey, namely a statue of a white monkey carved in 1989 from a branch of the shrine’s sacred tree (shinboku). The magnificent tree, a camphor, is 700 years old. According to the priest’s son, the shrine is even older.

The small shrine of Sarutahiko Jinja is not very well known and its set in the north-west in an unprepossessing part of Kyoto, sadly surrounded by some of the city’s uglier urban conglomeration. Nonetheless it possesses one of the most striking features in this year of the monkey, namely a statue of a white monkey carved in 1989 from a branch of the shrine’s sacred tree (shinboku). The magnificent tree, a camphor, is 700 years old. According to the priest’s son, the shrine is even older.