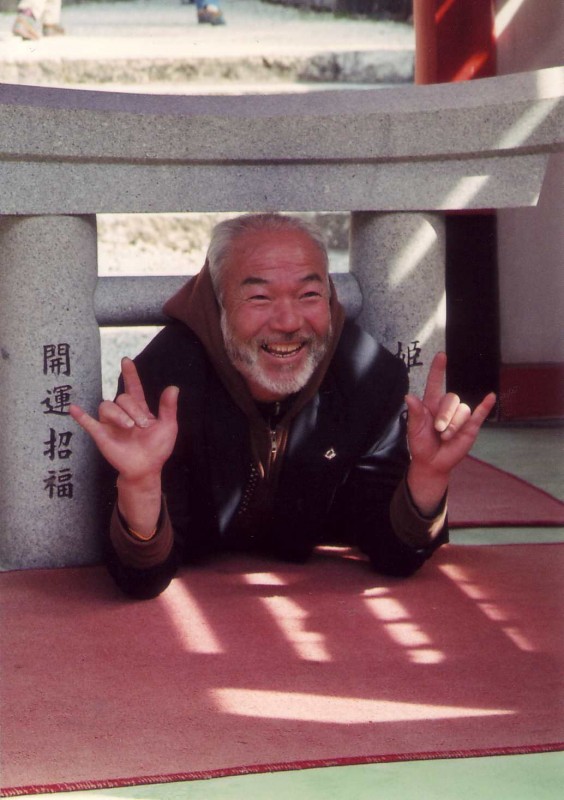

Morihei Ueshiba in 1939 (Wikicommons)

As the new year beckons, let’s hope that it ushers in a year of peace in place of the hatred and warfare of recent times. One man who realised the futility of aggression was the Shinto-inspired Morihei Ueshiba (1883-1969), who has been called ‘history’s greatest martial artist’.

The founder of aikido was born into a samurai family in Tanabe, Wakayama Prefecture. As a child he learnt something of Confucianism and Shingon Buddhism, as well as training in martial arts. He became the leader of a pioneer settlement in Hokkaido, and studied Daitō-ryū aiki-jūjutsu there. He then joned the Omoto sect in Ayabe, near Kyoto, working as their martial arts instructor, before moving to Tokyo and opening his own dojo.

Ueshiba came to the realisation that violence only prompts more violence, and he therefore promoted what he called the Art of Peace. From 1942 until his death, he was based at Iwama in Ibaraki Prefecture and the town hosts the world’s only shrine to aikido. It’s a place of pilgrimage for practitioners, and the annual festival on April 29th features a demonstration offering to the kami and a ceremony performed by Omoto sect priests.

Ueshiba drew inspiration for his martial art from the principles of Shinto, and the quotations below are taken from a compilation of his sayings. It’s a personal selection, which highlights the influence of Taoism (and thereby the closeness to Zen) in his thinking. The lines are taken from The Art of Peace by Morihei Ueshiba, translated by John Stevens and published by Shambhala in 2002.

**********

Everyone has a spirit that can be refined, a body that can be trained in some manner, a suitable path to follow. You are here for no other reason than to realize your inner divinity and manifest your inner enlightenment.

**********

All things, material and spiritual, originate from one source and are related as if they were one family. The past, present, and future are all contained in the life force…. Return to that source and leave behind all self-centred thoughts, petty desires, and anger.

**********

Now and again, it is necessary to seclude yourself among deep mountains and hidden valleys to restore your link to the source of life.

Now and again, it is necessary to seclude yourself among deep mountains and hidden valleys to restore your link to the source of life.

**********

All the principles of heaven and earth are living inside you. Life itself is the truth, and this will never change. Everything in heaven and earth breathes. Breath is the thread that ties creation together.

**********

Do not fail

To learn from

The pure voice of an

Ever-flowing stream

Splashing over the rocks.

***********

The Art of Peace originates with the flow of things – its heart is like the movement of the wind and waves. The Way is like the veins that circulate blood through our bodies, following the natural flow of the life force.

***********

As soon as you concern yourself with the ‘good’ and ‘bad’ of your fellows, you create an opening in your heart for maliciousness to enter. Testing, competing with, and criticising others weakens and defeats you.

***********

A true warrior is always armed with three things: the radiant sword of pacification; the mirror of bravery; and the precious jewel of enlightenment.

************

To practise properly the Art of Peace you must

• calm the spirit and return to the source

*cleanse the bod and spirit by removing all malice, selfishness, and desire

* be ever grateful for the gifts received from the universe, your family, Mother Nature, and your fellow human beings

************

To purify yourself you must wash away all external defilements, remove all obstacles from your path, separate yourself from disorder, and abstain from negative thoughts. This will create a radiant state of being. Such purification allows you to return to the very beginning, where all is fresh, bright, and pristine, and you will see once again the world’s scintillating beauty.

************

Loyalty and devotion lead to bravery. Bravery leads to the spirit of self-sacrifice. The spirit of self-sacrifice creates trust in the power of love.

************

The Divine is not something high above us. It is in heaven, it is in earth, and it is inside us.

************

The Divine does not like to be shut up in a building. The divine likes to be out in the open. It is right here in this very body. Each one of us is a miniature universe, a living shrine.

************

(For a remarkable two-and-a half-minutes video of Ueshiba demonstrating aikido as an old man, please see here. For a 26 minute documentary, click here.)

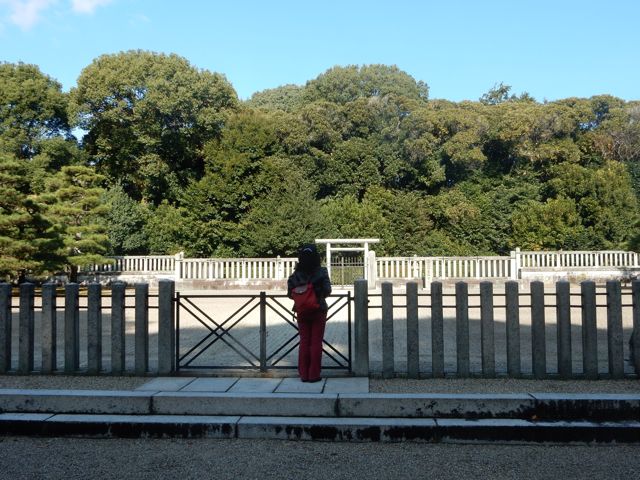

The Aiki Shrine in Iwama, founded by Morihei Ueshiba

As far as I know, there is no special celebration of the winter solstice in Shinto, preoccupied as it is with clearing away old impurities before the renewal of the year with Oshogatsu (New Year). However, it seems important that the shortest day of the year be marked in some way, and a visit to a power spot, whether real or virtual, seems in order. In this respect

As far as I know, there is no special celebration of the winter solstice in Shinto, preoccupied as it is with clearing away old impurities before the renewal of the year with Oshogatsu (New Year). However, it seems important that the shortest day of the year be marked in some way, and a visit to a power spot, whether real or virtual, seems in order. In this respect

Gokonomiya Shrine is not one of the better-known shrines of Kyoto, though in any other town it would certainly be a focus of attention. It was first mentioned in 862 as having been restored – which means it dates from an earlier time. It is said to have been built on the site of an imperial villa (Kyoto was founded in 794). The imperial connection is reflected in its enshrined deities, the legendary Empress Jingu and Hachiman (also known as her son, Emperor Ojin).

Gokonomiya Shrine is not one of the better-known shrines of Kyoto, though in any other town it would certainly be a focus of attention. It was first mentioned in 862 as having been restored – which means it dates from an earlier time. It is said to have been built on the site of an imperial villa (Kyoto was founded in 794). The imperial connection is reflected in its enshrined deities, the legendary Empress Jingu and Hachiman (also known as her son, Emperor Ojin).