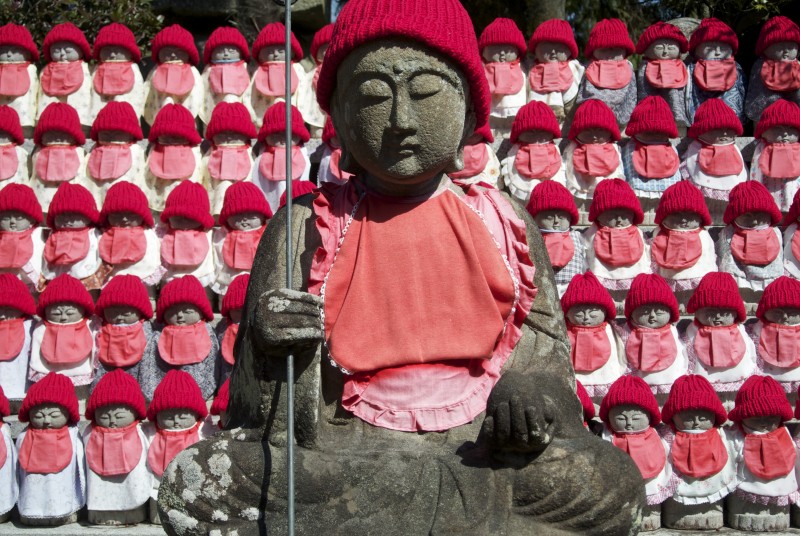

Jizo is the most widespread deity in Japan, to be seen across the country at crossroads, waysides, cemeteries and elsewhere. A guardian of the dead, he is portrayed in monk’s attire and seen as a guardian of the otherworld who ensures safe crossing, particularly for children. Though it’s customary to think of the deity as purely Buddhist, the passage below from Mark Schumacher’s onmark website shows that there is in fact a strong Shinto component.

Jizo is the most widespread deity in Japan, to be seen across the country at crossroads, waysides, cemeteries and elsewhere. A guardian of the dead, he is portrayed in monk’s attire and seen as a guardian of the otherworld who ensures safe crossing, particularly for children. Though it’s customary to think of the deity as purely Buddhist, the passage below from Mark Schumacher’s onmark website shows that there is in fact a strong Shinto component.

*************

Jizō incorporates many of the functions of Koyasu-sama (aka Koyasu-gami), the Shintō goddess of pregnancy, safe childbirth, and the healthy growth and development of children. Shintō shrines dedicated to Koyasu-sama still exist in modern times. These shrines are known as Asama Shrines (also pronounced Sengen).

Princess Konohanasakuya, patron of safe delivery as well as deity of Mt Fuji and cherry blossom

More than 1,000 Asama (Sengen) shrines exist across Japan, with the head shrines standing at the foot and the summit of Mount Fuji itself. These sanctuaries are dedicated to Koyasu’s namesake, the mythical princess Konohana Sakuya Hime, the Shintō deity of Mount Fuji, of cherry trees in bloom, and the patron of safe delivery.

In Shintō mythology, Konohana (lit = tree flower) is the daughter of Ōyamatsumi (the earthly kami of mountains). She was married to Ninigi (heavenly grandchild of sun goddess Amaterasu), became pregnant in a single night, and gave birth to three children while her home was engulfed in fire — thus her role as the Shintō kami who grants safe childbirth. In some accounts she died in the fire, and thus she is likened to the short-lived beauty of the cherry blossom.

Despite the survival of Shintō’s Koyasu-sama into modern times, she has been largely supplanted by her Buddhist equivalents, known as Koyasu Jizō, Koyasu Kannon, and Koyasu Kishibojin.

<Source: Konohana Sakuya Hime and Koyasu-sama; both from the Kokugakuin University Shintō Encyclopedia >

Jizo in his child-caring capacity

A reminder that tomorrow (Mon 28th) will be the harvest full moon, traditionally celebrated by the Japanese as the most beautiful of the year. There are lots of moon viewing parties, which in the past consisted of poetry making while sipping saké and admiring the reflection in a specially crafted cup. Japanese love of beauty at its best.

A reminder that tomorrow (Mon 28th) will be the harvest full moon, traditionally celebrated by the Japanese as the most beautiful of the year. There are lots of moon viewing parties, which in the past consisted of poetry making while sipping saké and admiring the reflection in a specially crafted cup. Japanese love of beauty at its best.

The following passage in praise of trees comes from Herman Hesse’s Baume: Betrachtungen und Gedichte (Trees: Reflections and Poems), 1984. It’s a beautiful piece of writing that speaks of a connection to the natural world and the happiness that comes from feeling at home in the universe.

The following passage in praise of trees comes from Herman Hesse’s Baume: Betrachtungen und Gedichte (Trees: Reflections and Poems), 1984. It’s a beautiful piece of writing that speaks of a connection to the natural world and the happiness that comes from feeling at home in the universe.