Herons view the evening sky with Mt Fuji in the background

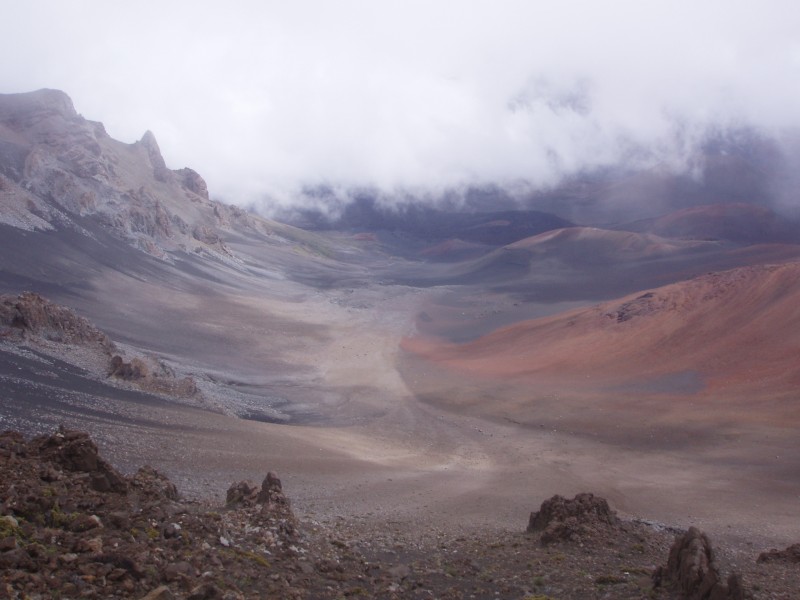

Mountains are a vital part of Japan’s identity, and Mt Fuji its sacred symbol. Some 70% of the country is mountainous, and the terrain is characterised by rice-growing villages set amongst steep hillsides. These ‘abodes of the gods’ have shaped the nation’s religious sensibility.

Not only are sacred mountains viewed as protective deities, but they serve sometimes as guardians of remote and scenically situated shrines. ‘Entering the mountains’ to develop spiritual merit started in prehistoric times and was moulded into a syncretic practice called Shugendo. Mountains took practitioners closer to god in more senses than one.

In the abridged book review below, Stephen Mansfield suggests that the sacred quality of mountains has been eroded in a secular age of tourism and environmental destruction. Even the volcano Mt Fuji, tallest and most beautiful of Japan’s mountains, has not escaped despoliation and overuse.

*************

On mountain peaks and tourist trash

Stephen Mansfield for The Japan Times July 5, 2015

Review of One Hundred Mountains of Japan, by Kyuya Fukada, Translated by Martin Hood. 246 pages University of Hawaii Press

Despite hazardous climatic conditions, treacherous features, and the large number of people who have come to grief on them, in his 1964 book Nihon Hyakumeizan (“One Hundred Mountains of Japan”) Kyuya Fukada highlights the benevolent characteristics of mountains, their function as protective sentinels and tutelary deities in the lives of those who inhabit surrounding villages and towns.

Fukada’s criteria in selecting peaks was based not on height or reputation, but the following: “A mountain must have character; it must have history; and it should have something that makes it uniquely itself — an extraordinary distinctiveness.” Accordingly, Fukada writes about each mountain as if it were a person, with a particular set of characteristics, strengths, flaws and defining identity. In the author’s view, a truly outstanding mountain should also be associated with religious traditions, and accord with his assertion that, “mountains have always formed the bedrock of the Japanese soul.”

Japanese holy men had long been ascending peaks, but it was only in the Meiji Era (1868-1912) that Englishman Walter Weston first introduced Japan to the notion of climbing mountains for the sheer pleasure and the exhilaration of the experience. Many a mountaineer has set out in earnest to “conquer” a peak, only to discover locals — hunters of serow and bear, or religious petitioners — have already been there, leaving small, unvarnished wooden shrines, votive tablets or old bronze coins as evidence of their ascents.

Borrowing from the nature writings of John Ruskin, Fukada shared the Victorian sage’s view of the ascent of mountains as a morally ennobling experience. If one part of Fukada was an unapologetic romanticist, the other half was a cynic — or at least a healthy skeptic.He asks, “Is Japan’s landscape doomed to be despoiled at the hands of the Japanese themselves?” Noting a stone monument to the poet Takuboku Ishikawa near the Akan-dake volcano complex in Hokkaido, Fukada writes, the “local tourist industry has battened on (Ishikawa) as the poet most likely to serve their commercial interests.” Passing a “touristified mock village,” he can barely conceal his derision at the sight of “people in Ainu costume sitting in their shop fronts carving wooden bears.”

It was still possible in Fukada’s early climbing days — with many trails relatively untrodden — to treat mountains as objects of reflection and meditation, a pleasure made feasible by a pristine landscape of snowfields, trackless wildernesses, watercourses and highland meadows bedizened with Japanese parsley, sorrel and white florets.

On Mount Iide, a peak in the Tohoku region, Fukada finds a rusty sword placed beside a stone marking the summit. At another spot near a shrine standing beside a grove, he finds antique pottery fragments in a shallow streambed.

The writer knew these peaks before the era of mass tourism, ski lifts and easy access; his later encounters were with increasingly less naturalistic landscapes. On the slopes of Mount Azuma, Fukuda finds once-virgin terrain that has not been able to withstand the attentions of commercial developers. He warns that at the height of the tourist season, “you would be well advised to don a mask if walking in the vicinity, so dense are the dust and fumes.”

Fukada finds old huts and lodgings, once intended as shelter for pilgrims and mountain mystics, which have been converted into modern inns and a sprawl of facilities catering to the contemporary visitor. On Mount Takazuma, a sacred place for both Shinto and Buddhist worship, Fukada finds a spot that was “once the haunt of cognoscenti who shunned the vulgarities of Karuizawa and lake Nojiri” has now been reduced to “just another tourist trap.”

None of Fukuda’s harshest criticisms, however, detract from the intrinsic beauty of his 100 peaks, or their forms, which have remained essentially intact. In his climbs, the writer’s senses sharpened on the grindstone of these mountains, Fukada shares the sheer joy of being alive amid such magisterial eminencies.

Primal mountain… it was here on Mt Takachiho that the heavenly deities first descended to earth in the person of Ninigi-no-mikoto

Ray Tsuchiyama has written in with an article which appeared in an edition of Hana Hou!, the magazine of Hawaiian Airlines. Entitled The Last Jinja, it tells the story of the last standing shrine on the island of Maui. When I visited it some ten years ago, it looked forlorn and largely unused. I knew there was an elderly priestess in charge, but Ray’s article below explains the whole history that lies behind the building. It’s a fascinating story.

Ray Tsuchiyama has written in with an article which appeared in an edition of Hana Hou!, the magazine of Hawaiian Airlines. Entitled The Last Jinja, it tells the story of the last standing shrine on the island of Maui. When I visited it some ten years ago, it looked forlorn and largely unused. I knew there was an elderly priestess in charge, but Ray’s article below explains the whole history that lies behind the building. It’s a fascinating story.