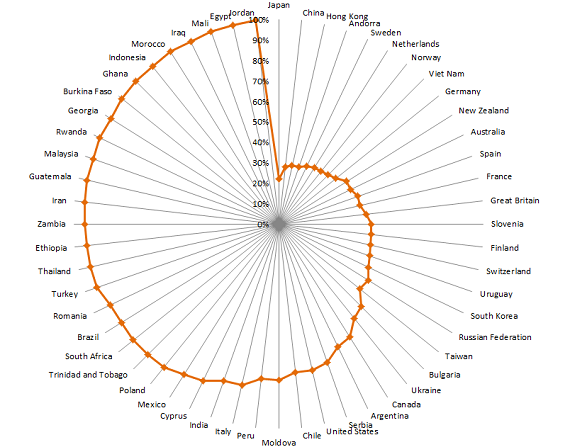

Anime and manga depictions are increasingly common on ema as shrines seek new ways of increasing their popularity

An article in the English-language Asahi newspaper talks of Tokyo’s Kanda Myojin as one of some 30 shrines around the country to have become a destination for fans of certain anime or manga. Green Shinto has dealt with the subject before. Some may see it as a trivialisation of sacred space, but priests and anthropologists counter this with such statements as, “Since ancient times, Shinto shrines have not been exclusive. It’s good if they are talked about and become attractive destinations.”

***************************************************

Kanda shrine enlists anime favorites to draw in younger visitors

By ORIE YOSHIHAMA/ Staff Writer, The Asahi, April 25, 2015

Love Live! ema

A shrine in Tokyo’s Kanda district is offering lucky amulets adorned with anime girls and wooden prayer tablets featuring fictional characters in a bid to lure a younger generation of worshippers. The Kanda Myojin shrine, the grand guardian for Edo, or present-day Tokyo, has spent about 400 years at its current location, which is just a short jump from the otaku (literally “geek”) subculture hub of Akihabara.

It decided on the “makeover” in response to a new-found popularity among anime fans, many filtering in from the anime, manga and electronics district. “There they are!” one 22-year-old graduate student from Fukui Prefecture exclaimed in front of the festival office building on the premises of the Kanda Myojin. What he found were illustrated ema tablets and lucky amulets featuring a character from the animated series “Love Live! School Idol Project” dressed as a “miko” shrine maiden.

“Love Live!” is set in an area surrounding Akihabara. The story centers around a group of nine high school girls who try to become pop idols to save their school from being shut down. Manga and video game adaptations of the series have also become popular. A throng of fans of the series frequent the shrine, which became one of their “pilgrimage destinations” after being featured in the anime.

Love Live! lucky charm

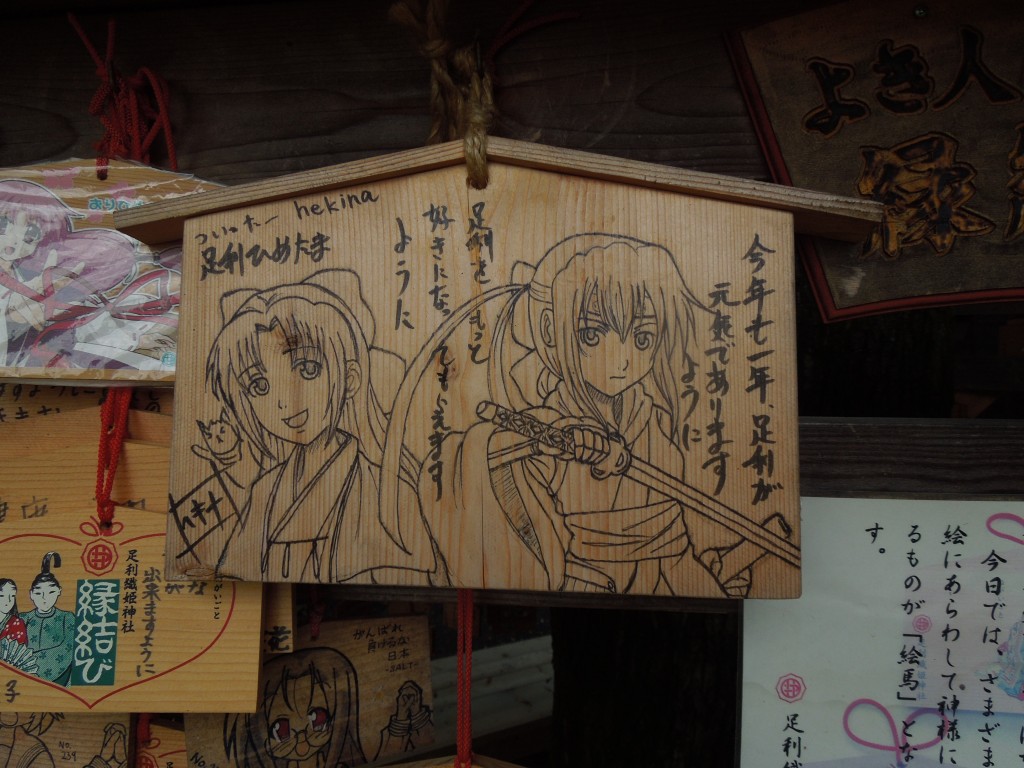

Visitors can see a plethora of ema tablets with “Love Live!” characters and other illustrations drawn by anime followers hanging at the shrine. The items have been dubbed “ita-ema” (painful ema), an otaku term coined after “ita-sha” (painful cars), referring to cars carrying flamboyant anime illustrations that can be “painfully embarrassing.” Some fans also put anime figures on the stone steps of the Myojin Otokozaka slope to take pictures.

The first batch of “Love Live!” ema tablets and lucky amulets was delivered to the shrine in November last year after the production studio responsible for the anime series agreed to a collaboration with shrine officials. Hundreds of fans flooded the shrine in response, and the items immediately sold out. Since then, the goods continue to go out of stock soon after they are delivered.

The anime characters will also be featured in a poster for the Kanda Matsuri festival, one of the nation’s three largest festivals, held annually in May, the officials said.

The graduate student learned about the shrine from the anime and visited last year for the first time. He made his third visit before attending a live concert featuring voice actresses held in Saitama. About 50 fans like him were waiting in line at the shrine, he added.

“I was surprised to see so many young men visiting (the shrine) last year,” said Masanori Kishikawa, a “gonnegi” junior priest at the shrine. “It happened to be the day a live concert was held.”

Banner at a shrine in Gunma advertising its connection with a well-known manga

At first, he was baffled by the popularity, with ita-sha cars gathering at a spot near the shrine. But now, the 41-year-old is delighted that young people who may have been previously estranged from shrines are paying visits.

“Everyone offers prayers in a proper manner. Whatever their motives are, I hope they become interested in learning about Japanese traditions,” Kishikawa added.

Founded nearly 1,300 years ago, Kanda Myojin was moved to its current Sotokanda site in 1616 as part of the Tokugawa Shogunate’s project to expand Edo Castle. In addition to attracting more than 400,000 people for their first visit of the year to a shrine, it has also served as a popular wedding venue for many celebrity couples.

The shrine has incorporated fresh ideas, such as amulet stickers for IT workers that can be posted on personal computers, while staying faithful to its long-established traditions and prestige.

This year, the shrine collaborated with one of its supporting companies to introduce a vending machine that dispenses toys in capsules, including miko figurines. “The ‘kami’ (god) always listens to the wishes of modern people. Shrines are also sightseeing spots. The new and the traditional are integrated there,” Kishikawa said, adding that the shrine’s collaboration with “Love Live!” is not unusual.

Many other Shinto shrines have become pilgrimage destinations after being featured in anime and manga works. The most common among them is Washinomiyajinja shrine in Kuki, Saitama Prefecture, where “Lucky Star” was set. In the five years since an animated TV series adaptation of the manga of the same name started airing in 2007, the number of people who chose the shrine for their first visit of the year spiked by about five times, to 470,000.

Other such sites include the Oarai Isosakijinja shrine in Oarai, Ibaraki Prefecture, featured in “Girls und Panzer”; the Chichibujinja shrine in Chichibu, Saitama Prefecture, featured in “Anohana: The Flower We Saw That Day”; and the Omijingu shrine in Otsu, Shiga Prefecture, featured in “Chihayafuru.”

According to a survey by Takeshi Okamoto, an instructor of tourism sociology at Nara Prefectural University who studies pilgrimages to locations featured in manga and anime, there are at least 30 such locations across Japan.

Asked why shrines serve as pilgrimage sites, Okamoto said they can be a “third place” that is neither home nor school nor the workplace, where anyone can visit anonymously.

It may also be connected to the freedom that allows for the acceptance of different values, he noted. The lecturer said shrines evoke sympathy and curiosity from younger generations by being featured in anime and manga. “Real connections are made through pilgrimages, and a new culture is formed,” Okamoto said. “The two cultures that Japan takes pride in are developing as they are engaging each other.”

Keiji Ueshima, an anthropologist of religion, pointed out that mythologies, anime and manga are common in that they are all set in a world different from reality. A recent trend, along with growing demand, for “experiences like no other” rather than “the consumption of things” bears this out, Ueshima said.

While there are voices expressing concerns about the secularization of sacred spaces, Ueshima and Okamoto, who both love manga, are not worried. “Since ancient times, Shinto shrines have not been exclusive,” the two said. “It’s good if they are talked about and become attractive destinations.”

These days it's not unusual to see do-it-yourself fan versions of manga and anime