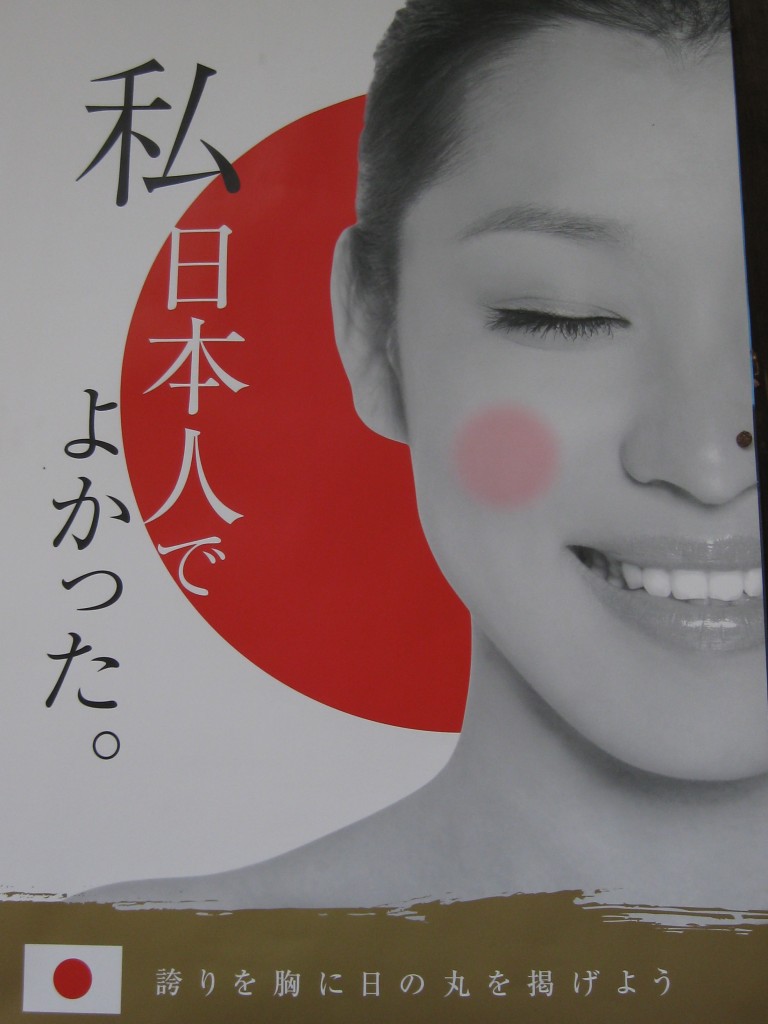

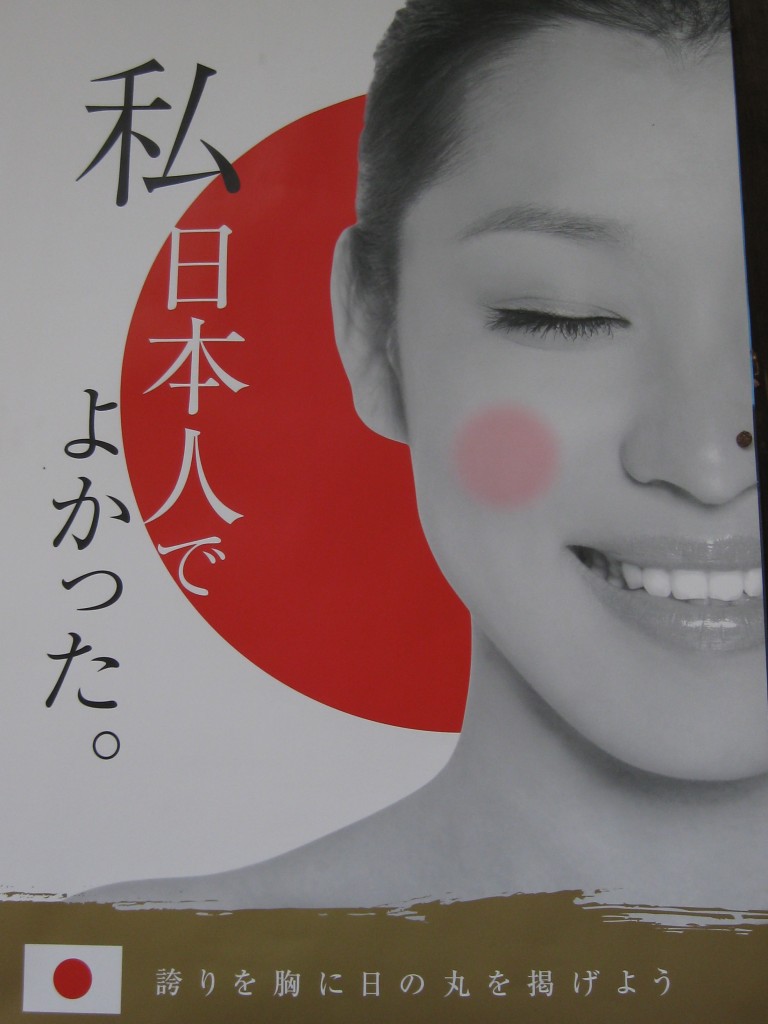

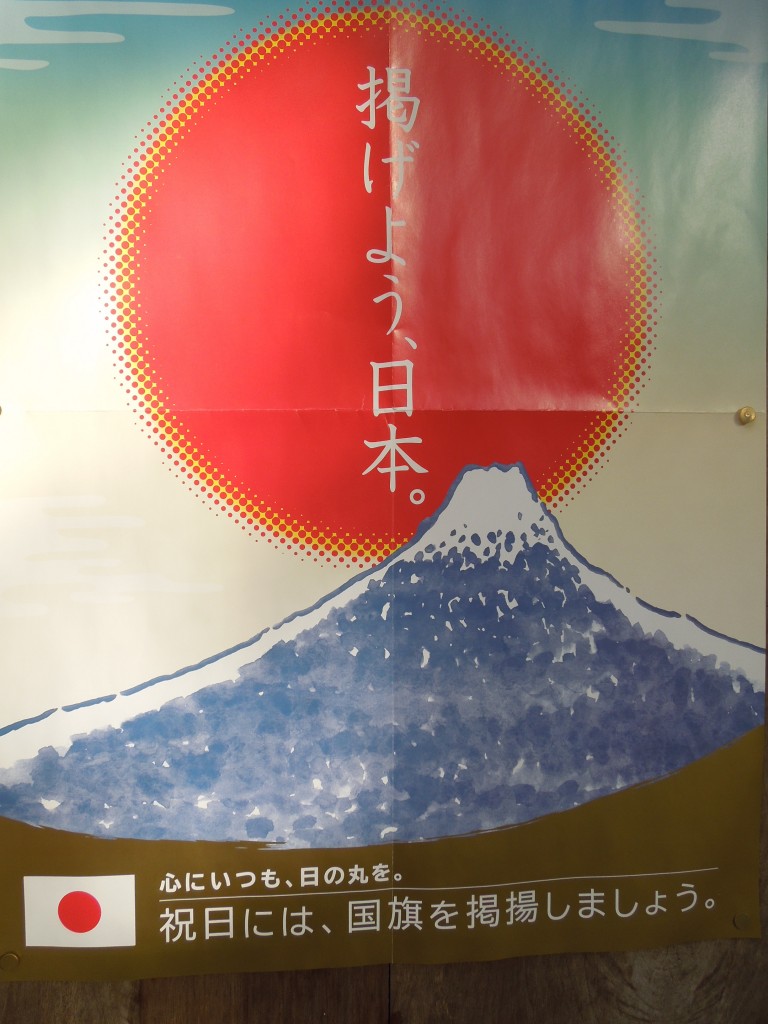

Religion or patriotism? (photo courtesy Japan Times)

Shinto and Japaneseness are closely intertwined. Indeed, scholars such as Ian Reader have described Shinto precisely as a religion of Japaneseness. Not only are Shinto values fundamental to the culture, but it’s often difficult to separate the two. For many commentators, being born Japanese means to have an instinctive Shinto attitude to life. And it is common to find definitions of Shinto as a religion of the Japanese people, in much the same way as Judaism is said to be a religion for Jews. To be born Japanese is to be born Shinto.

Anyone who has lived in Japan for a while will be aware of a certain insularity that shapes the Japanese worldview. This finds its most obvious outlet in the popular genre known as Nihonjinron (the theory of what it is to be Japanese). All kinds of books, many of them bestsellers, set out to explain what is peculiar about the Japanese and why they are different from others. This is predicated on the notion that Japanese are homogenous, monoracial, and share a common heritage. Shinto reinforces the idea, by claiming that Japan is uniquely a land of kami from whom the people are descended. This makes them special, in particular the emperor. After the Meiji Restoration the thinking became state ideology, and oddly enough it still remains current in today’s ‘democratic Japan’.

In the article below, these ideas are explored at greater length. Some might find the points overstated, but nevertheless there is little doubt that insularity has gained greater strength under the nationalist-leaning Shinzo Abe. Some of the thinking is worryingly regressive. In contrast to the openness, fraternisation, internationalisation and universalism that one might hope the human race was striving towards, Japaneseness as an inward-looking religion appears to be firmly in place.

****************************************************************************

Viewed through a religious lens, Japan makes more sense

BY DEBITO ARUDOU APR 5, 2015 Japan Times

Ever noticed how Japan — and in particular, its ruling elite — keeps getting away with astonishing bigotry? Recently Ayako Sono, a former adviser of the current Shinzo Abe government, sang the praises of a segregated South Africa, effectively advocating a system where people would live separately by race in Japan (a “Japartheid,” if you will). But that’s just the latest stitch in a rich tapestry of offensive remarks.

Remember former Tokyo Gov. Shintaro Ishihara’s claim that “old women who live after losing their reproductive function are useless and committing a sin,” or his attribution of Chinese criminality to “ethnic DNA” (both 2001)? Or former Prime Minister Taro Aso admiring Nazi subterfuge in changing Germany’s prewar constitution (2013), and arguing that Western diplomats cannot solve problems in the Middle East because of their “blue eyes and blond hair” — not to mention advocating policies to attract “rich Jews” to Japan (both 2001)? Or then-Prime Minister Yasuhiro Nakasone declaring Japan to be “an intelligent society” because it was “monoracial,” without the “blacks, Puerto Ricans and Mexicans” that dragged down America’s average level of education (1986)?

Although their statements invited international and domestic protest, none of these people were drummed out of office or even exiled to the political wilderness. Why? Because people keep passing off such behavior as symptomatic of “weird, quirky Japan,” i.e., “They say these things because they are Japanese — trapped in uniquely insular mentalities after a long self-imposed isolation.”

Such excuses sound lame and belittling when you consider that it’s been 160 years since Japan ended its isolation, during which time it has successfully copied contemporary methods of getting rich, waging war and integrating into the global market.

This treatment also goes beyond the blind-eyeing usually accorded to allies due to geopolitical realpolitik. In the past, analysts have gone so gaga over the country’s putative uniqueness that they have claimed Japan is an exception from worldwide socioeconomic factors including racism, postcolonial critique and (until the bubble era ended) even basic economic theory!

This treatment also goes beyond the blind-eyeing usually accorded to allies due to geopolitical realpolitik. In the past, analysts have gone so gaga over the country’s putative uniqueness that they have claimed Japan is an exception from worldwide socioeconomic factors including racism, postcolonial critique and (until the bubble era ended) even basic economic theory!

So why does Japan keep getting a free pass? Perhaps it’s time to start looking at “Japaneseness” through a different lens: as a religion. It’s more insightful.

A comprehensive but concise definition of “religion” is “a set of beliefs concerning the cause, nature and purpose of the universe, especially when considered as the creation of a superhuman agency or agencies, usually involving devotional and ritual observances, and often containing a moral code governing the conduct of human affairs.”

Japaneseness qualifies. A set of beliefs ordering the “Japanese universe” is available at your nearest big bookstore, where shelves groan under the wiki-composite pseudoscience of Nihonjinron (the “Theory of The Japanese”), a lucrative market for navel-gazing about what Japanese allegedly think or do uniquely and collectively.

Japan also has its own creation myth grounded in mystical immortals (the goddess Amaterasu et al), with enough currency that a sitting prime minister, Yoshiro Mori, once publicly claimed Japan was “a nation of deities (kami no kuni) with the Emperor at its center,” in which Japanese have seen “beings above and beyond humankind” (2000). Seen in this way, Japan transcends the mere nation-state to become something akin to a holy land.

Devotional and ritual observances involve not only an imported and adapted foreign religion (Buddhism) hybridized with an established state religion (Shinto), but also elements of animism and ancestor worship whose observances regularly reach down to the level of the neighborhood (o-mikoshi festival portable shrines) and even the household (butsudan shrines).

In the mythology, the primal pair of Izanagi and Izanami were not creators of the world, but created the eight islands of Japan.

As for a moral code governing conduct, Japanese media offer plenty of ascriptive programming (e.g., NHK’s popular quiz show “Nihonjin no Shitsumon” or “Questions The Japanese Ask” — as if that’s a discernible genre). They broadcast an unproblematized uniformity of “Japanese” thought, belief and morality generally offset from the remainder of the heterodox world.

Thus this religion-like phenomenon, because of the knock-on effects of vague mysticism and faith, goes beyond regular nationalism. For one thing, unlike nationalism, religion doesn’t necessarily need another country to contrast and compete with — Japanese are sui generis special because they are a family descended from gods. For another, nationality can be obtained through law, but bloodline descent cannot — and blood is what makes someone a “real” Japanese. Further, how can you ever offer a counter-narrative to a myth? (For a national narrative, you can offer a different historical interpretation of mortals and events; it’s far tougher to argue different gods.)

These dynamics have been covered in much literature elsewhere — in fact, they are depicted positively by the Nihonjinron high priests themselves — but few people consider three other effects of religiosity.

First, there’s religion’s enhanced political power in prescribing and enforcing conformity. If media uncritically establish how “normal Japanese” act, then deviant thoughts and behaviors not only become “unusual” but also “un-Japanese.” It’s not a big leap from the “science” of what people naturally do as Japanese to the science of what to do in order to be Japanese. There is an orthodoxy to be followed, or else.

This dynamic also robs dissidents of the power to use reason to adjust society’s course. Instead of social mores being codified in the rule of law or grounded in terms of concrete “rights, privileges and duties” of a nation-state, they are molded case by case to suit an alleged “consensus feeling” of an abstract group, sending signals through the media or just through “the air” (which people are supposed to “read”: kūki o yomu).

Shinto posters can be heavily patriotic: 'It's good that I'm Japanese,' says this one.

How can one reason with or argue against an amorphous “understanding” of things, or summon enough energy to push against an invisible enfranchised opponent? Easier all around to fall back on the default shikata ga nai (“There’s nothing I can do”) attitude, meaning Japanese will police each other into acceptance of the status quo.

The second effect of this phenomenon is the corruption of social science. The broad-stroke categorization inherent to “groupism” normalizes the pigeonholing of peoples. In Japan, this has reached the point where influential people openly espouse fallacious theories, such as that eye color affects vision quality, blood type affects personality and race/country of origin/gender influence intellectual ability or talent (e.g., “Indians are good programmers,” “Jews are rich,” “Chinese have criminal DNA”).

Although stereotypes exist in every society, in Japan they underpin and blinker most social science. In fact, learning the stereotypes is the science.

The third effect is religion’s enhanced rhetorical power, and this projects influence beyond Japan’s borders. If Japan’s behavior was merely seen as a matter of nationalism, then things could be explained away in terms of furthering national interests under rational-actor theory. But they’re not. Again, “quirky” Japanese get away with weird stuff like bigotry because they are treated with the deference traditionally accorded to a religion.

Scholar Richard Dawkins put it best: “A widespread assumption . . . is that religious faith is especially vulnerable to offence and should be protected by an abnormally thick wall of respect.” Author Douglas Adams expounds on this idea: “Religion . . . has certain ideas at the heart of it which we call sacred or holy or whatever. What it means is, ‘Here is an idea or a notion you’re not allowed to say anything bad about. You’re just not.’

“If somebody votes for a party that you don’t agree with, you’re free to argue about it as much as you like. . . . But on the other hand if somebody says, ‘I mustn’t move a light switch on a Saturday,’ you say, ‘I respect that.’ ”

Likewise, you must respect Japan, and woe betide you if you criticize it. Decry even the most egregious bad behavior, such as the whitewashing of an exploitative empire’s history into an exculpated victimhood, and you will be branded “anti-Japan,” a “Japan-hater” or “Japan-basher” by the reactionary cloud of anonyms that so dominate Japan’s Internet.

Likewise, you must respect Japan, and woe betide you if you criticize it. Decry even the most egregious bad behavior, such as the whitewashing of an exploitative empire’s history into an exculpated victimhood, and you will be branded “anti-Japan,” a “Japan-hater” or “Japan-basher” by the reactionary cloud of anonyms that so dominate Japan’s Internet.

This trolling wouldn’t matter if that cloud was ignored for what it is — a bunch of anonymous craven cranks — but otherwise sensible people steeped (or academically trained) in Japan’s mysticism tend to take these disembodied opinions from the air seriously. Instead, the critic loses credibility and, in extreme cases, even their livelihood for not toeing the line. Japan is sensitive, and you’re not allowed to say anything bad about it. You’re just not.

This is one reason why even the most scientifically trained among us is ready, for example, to take seriously the comment of a single native-born Japanese (rather than trust qualified Japan experts who unfortunately lack the mystical bloodline) as some kind of evidence in any discussion on Japan. Every Japanese by blood and dint of being raised in the temple of Japanese society is reflexively accorded the right to represent all Japan. It’s respectful, but it also blunts analysis by keeping discussion of Japan within temple control.

So, whenever Japan makes mystical arguments — about, say, longer intestines, special soil and snow or the country’s unique climate — for political ends (to justify banning imports of beef, construction equipment, skis, rice, etc.), skittish outsiders tend to be deferential to the nonsense because of Japan’s “uniqueness” and respectfully ease off the pressure.

Or when Japan’s rulers coddle war-mongering rightists (who also advocate Japan’s mysticism) and sanction pacifist leftists (who more likely see religion as a mass opiate), relax — that’s just how Japan maintains its unique social order. And if that social order is ever questioned, especially by any Japanese, that is treated as heresy or apostasy, drawing the threat of reprisal — if not violence — from zealots. After all, you do not question faith — or it would no longer be faith. You just don’t.

In sum, seeing Japaneseness through the prism of religion helps explain better why the world accommodates Japan egregiously excepting and offsetting itself. It may be time to abandon simple political theory (seeing Japan’s polity in terms of rational actors with occasional inexplicable irrationalities) in favor of the sociology of religious cults.

Specifically, this would mean studying Japan’s cult of personalities, i.e., the way a ruling elite is resurrecting mysticism and exploiting the reflexive deference usually reserved for religion to game the system. This is especially important now, as Japan’s rulers indulge in belligerent behavior — historical revisionism, remilitarization and so on — that’s helping destabilize the region.

Shinto and Japaneseness are often closely identified

BlueSky is a Mongolian shaman, author and director of The Institute for the Study of Mongolian Shamanism, living in Ulaanbaatar in Mongolia. In the latest edition of the Sacred Hoop magazine (Issue 87, spring 2015, p.42) he writes about an incident that is reminiscent of the founding story of Fushimi Inari, which involves shooting arrows on a hillside. The fox as spirit guide is common to both traditions.

BlueSky is a Mongolian shaman, author and director of The Institute for the Study of Mongolian Shamanism, living in Ulaanbaatar in Mongolia. In the latest edition of the Sacred Hoop magazine (Issue 87, spring 2015, p.42) he writes about an incident that is reminiscent of the founding story of Fushimi Inari, which involves shooting arrows on a hillside. The fox as spirit guide is common to both traditions.

This treatment also goes beyond the blind-eyeing usually accorded to allies due to geopolitical realpolitik. In the past, analysts have gone so gaga over the country’s putative uniqueness that they have claimed Japan is an exception from worldwide socioeconomic factors including racism, postcolonial critique and (until the bubble era ended) even basic economic theory!

This treatment also goes beyond the blind-eyeing usually accorded to allies due to geopolitical realpolitik. In the past, analysts have gone so gaga over the country’s putative uniqueness that they have claimed Japan is an exception from worldwide socioeconomic factors including racism, postcolonial critique and (until the bubble era ended) even basic economic theory!

Likewise, you must respect Japan, and woe betide you if you criticize it. Decry even the most egregious bad behavior, such as the whitewashing of an exploitative empire’s history into an exculpated victimhood, and you will be branded “anti-Japan,” a “Japan-hater” or “Japan-basher” by the reactionary cloud of anonyms that so dominate Japan’s Internet.

Likewise, you must respect Japan, and woe betide you if you criticize it. Decry even the most egregious bad behavior, such as the whitewashing of an exploitative empire’s history into an exculpated victimhood, and you will be branded “anti-Japan,” a “Japan-hater” or “Japan-basher” by the reactionary cloud of anonyms that so dominate Japan’s Internet.

“Efforts to honor shrine and temple etiquette reveal an intuitive understanding that adhering to established ritual is the only way to truly enter into ancient traditions.”

“Efforts to honor shrine and temple etiquette reveal an intuitive understanding that adhering to established ritual is the only way to truly enter into ancient traditions.”