A priest arranges the five-coloured banner of the masakaki at Yasaka Jinja in Kyoto

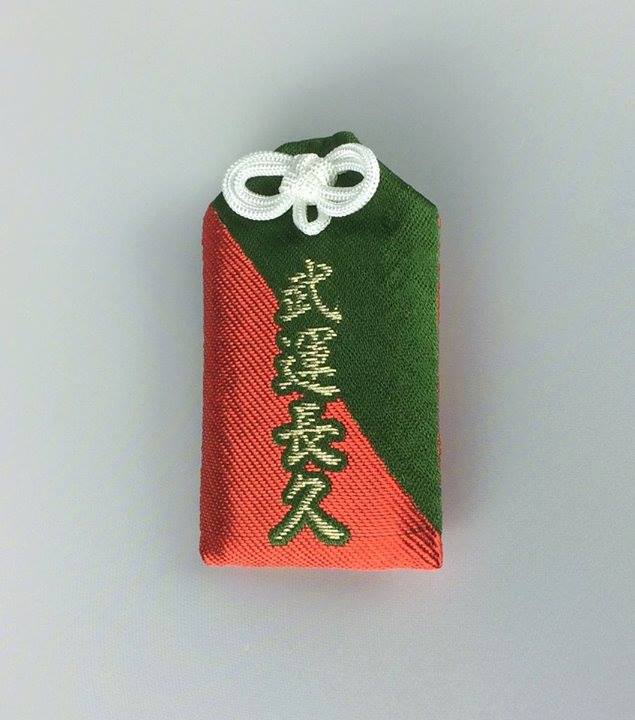

Green Shinto is delighted to present a learned article by Australian academic, Jann Williams, who has been exploring the use of elements in Japan. In the article below, she looks in particular at why Shinto uses certain colours for its masakaki banners. These are first mentioned in the mythology, but were formalised in 1875 in the Rules for Ritual Procedure at Shrines. According to the Encyclopedia of Shinto, the term masakaki “is used to refer to two poles of Japanese cypress (hinoki), to the tips of which are attached branches of sakaki, and below which are attached five-color silks (blue, yellow, red, white, and purple). The pole on the right (when facing the shrine) is decorated with a mirror and a jewel, and the one on the left with a sword.”

*********************************************************

The Colours of Shinto (or The elements of Shinto)

Professor Jann Williams, Tasmania, Australia April 3, 2015

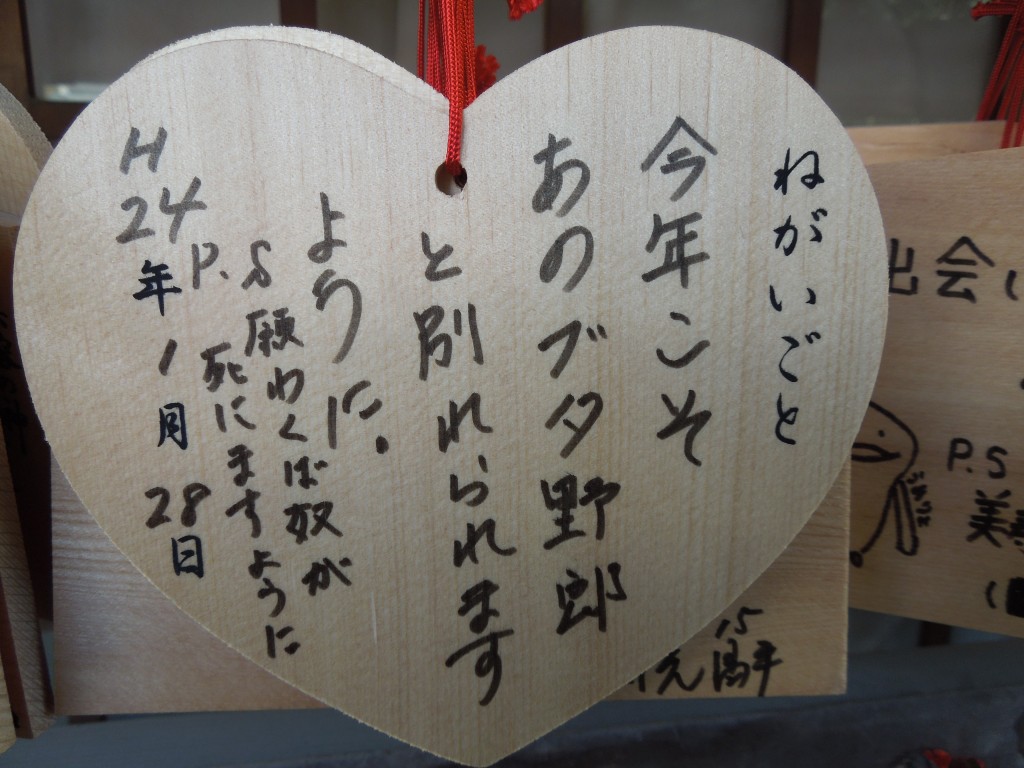

The mirror and jewels tell us this masakaki stands on the right-hand side of the shrine

In August 2014 Green Shinto’s Facebook page carried a piece about the ceremonies held at Yasaka Jinja in association with the end of the Gion Festival. A focus of the post was the meaning of the five colours associated with masakaki decoration a priest was attending to at the shrine. Several interpretations of the colours were given in response. In this update I’ll summarise these different ideas and bring a further perspective – one based on the elements.

On the Green Shinto Facebook site, the question was posed as to whether the colours were the same as those used in Pure Land Buddhism, with the symbolism differentiated at some point to fit with Shinto. In response to this suggestion, links were given in the comments to the onmarkproductions Buddhist material on Goshiko (Five colours) and Goseishoku (Five primary colours); a possible link to the Daoist association with the five phases was raised, and a suggestion made to contact Rev Barrish at the Tsubuki Grand Shrine in the US. The response he provided went as follows:

“The five colours of the masakaki banner, which has its origins in the decorations of the sakaki tree outside Amaterasu’s Cave: “Black (purple) means North (Ara Mitama), Blue (green) means East (Kushi Mitama), Red means South (Sachi Mitama), White means West (Nigi Mitama), Yellow means the sacred Center (Nao-Hi =sun rays).”

These responses give a sense of the potential influences on the colours of Shinto. The diversity in Goshiko is summarized on the Daruma Museum blogspot, which gives both Buddhist and Shinto examples (see http://darumamuseum.blogspot.com.au/2010/02/goshiki-five-colors.html).

My interest in the colours of Shinto comes from a broader exploration of the elements in Japan. In my experience the two are intimately related. The elements are a vast and complex topic, so these observations are bound to be refined over time. In my preliminary research there appears to be three main streams related to the elements in Japan, relevant both historically and in modern times:

1) Gogyo – the five phase (element) philosophy (earth, fire, water, metal and wood) associated with the Tao/Chinese philosophies of Yin Yang and Wu Xing. This system was used to varying degrees by the Bureau of Onmyo (Onmyo-ryo) in Japan for over 1000 years and expresses itself in many ways (e.g. in divination, the tea ceremony, the placement of buildings; the original Japanese calendar);

2) Godai – the ‘Five Great’ Elements in Japanese Buddhism (earth, fire, water, air/wind, space/void), originating in India and coming to Japan via China. These elements are found in the Book of Five Rings and are used by the ninja, amongst other martial arts;

3) Rokudai – the ‘Six Great’ Elements of esoteric Shingon Buddhism (earth, fire, water, air, space/void and consciousness), again coming to Japan from India via China.

The lefthand pole has a sword, at the top of which sits a branch of the sacred sakaki tree, festooned with white strips of paper (known as shide).

The Tao/Chinese and Buddhist/Indian philosophies of the elements have a long history in Japan, which has blended these into its own way of doing things. Shinto is no exception, having been influenced by each of these philosophies. This is not surprising given its syncretic nature. I have no doubt that the more I explore this area the more nuances will arise, especially in relation to the different Buddhist sects.

In each of the three main streams above the different elements, except consciousness (although perhaps this is ‘clear light’?), are related to different colours, as well as directions and other characteristics. For this post the relevant information about colours and the elements follows:

- Gogyo: Black/purple = water; Blue/green = wood/tree; Red = fire; White = metal and Yellow = earth;

- Godai – different combinations of colours and the elements are found in different Buddhist sects. A common combination described on the onmarkproductions site is: Black/purple = space/void; Blue/green = earth; Red = fire; White = wind/air and Yellow = water;

- Rokudai: Green = air; Blue = water; Red = fire; White = space and Yellow = earth (japanesesymbolsofpresence.com; consciousness isn’t included in their description).

So do the five colours of Shinto reflect the Gogyo or the Godai (Rokudai is included here) philosophies, or both? I’ve read that the five coloured Shinto banners are particularly found in shrines with strong Buddhist connections. This suggests a possible Godai connection to the banners.

The influence of Yin Yang and the five phases on Shinto is well documented so could also be reflected in the five colours found at shrines. The colours associated with Gogyo certainly seem to match those found there. The Gogyo colour/element combination is consistently applied as far as I’m aware, whereas the Buddhist combination varies depending on the sect. If the five Shinto colours are also consistent across shrines it suggests a possible influence by the Onmyo-ryo.

Getting back to my question then. For a number of reasons I’m currently leaning towards the five colours in Shinto and their related elements, directions etc. have their origins in Yin Yang and the five phases/Gogyo. I’m hoping that this statement will generate some debate! Perhaps the topic has already been systematically addressed and I haven’t discovered it yet. So far though I have mainly come across sometimes selective, sometimes contradictory and sometimes concealed views on the elements in Japan. That makes the research all the more interesting.

The elements are used in at least one different context in Shinto. In the book Kami no Michi by Yamamoto Yukitaka the words “purify the six elements of existence” are chanted during the ritual of misogi harai. These are a different set of ‘elements’ again.

It seems this practice has been adopted from Shugendo Buddhism and that the six ‘elements’ in this case relate to purification of the six senses – sight, hearing, smell, taste, mind and body. These senses, described as ‘rokon shojo’ in Japanese, have been translated as ‘six elements’, ‘six paths’ and the ‘six sacred roots.’ As noted, the study of the elements in Japan is vast and complex.

**************

Shusse Inari Jinja of America gives this advice for the use of masakaki with home altars:

- Masakaki: A pair of wooden poles topped with a sakaki (evergreen branch). Hanging from each pole are five colored silks of green, red, white, purple, and yellow representing the directions east, south, west, north, and center, respectively. The Sanshu no Jingi (Three Sacred Treasures) also hang from the masakaki. Place the masakaki with the mirror and jewel to the right of the kamidana, and the one with the sword to the left.

The use of sakaki as a sacred evergreen dates back to the Kojiki, where it is used at the festival to draw Amaterasu out of her cave and decorated with jewel beads, a mirror, and cloth (possibly coloured strips as in shamanism).

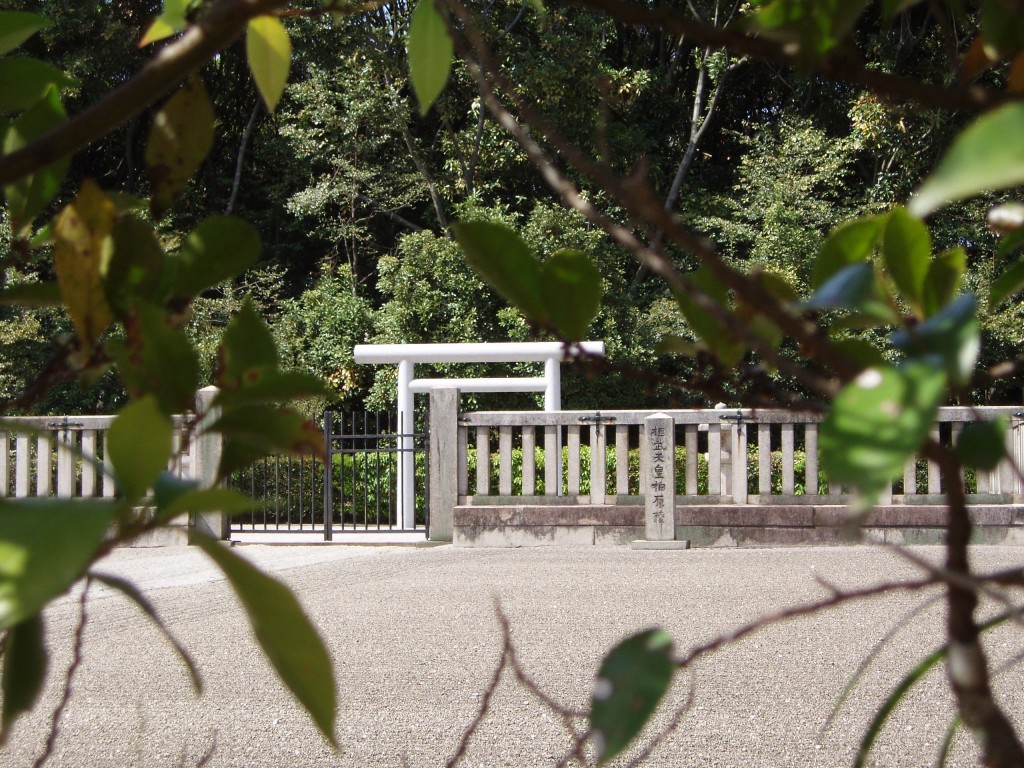

Hirano Jinja is one of thirteen Kyoto shrines in Cali and Dougill’s Shinto Shrines: A Guide to the Sacred Sites of Japan’s Ancient Religion (Univ of Hawaii, 2013). From that we learn the shrine was founded in 782 in Nara, before being relocated to the new capital of Heiankyo (Kyoto) in 794. The present buildings date from 1625, and with their unpainted wood and cypress-bark tiles they present an evocative rustic appearance.

Hirano Jinja is one of thirteen Kyoto shrines in Cali and Dougill’s Shinto Shrines: A Guide to the Sacred Sites of Japan’s Ancient Religion (Univ of Hawaii, 2013). From that we learn the shrine was founded in 782 in Nara, before being relocated to the new capital of Heiankyo (Kyoto) in 794. The present buildings date from 1625, and with their unpainted wood and cypress-bark tiles they present an evocative rustic appearance.

Previously, on the 1st of January 2015 from 2 am, a ritual for good luck in combat for the French Foreign Legion had been held at the Sanctuary Yabuhara. During the ceremony,there was an offering of a pair of Kagami-Mochi (round rice cakes) and three bottles of red wine brewed by the French Foreign Legion.

Previously, on the 1st of January 2015 from 2 am, a ritual for good luck in combat for the French Foreign Legion had been held at the Sanctuary Yabuhara. During the ceremony,there was an offering of a pair of Kagami-Mochi (round rice cakes) and three bottles of red wine brewed by the French Foreign Legion.