As an animist religion, Shinto sees the spirit world as underpinning that of the physical. This is true too of the traditional swords, thought to have a spiritual presence. ‘The forging of a Japanese blade typically took weeks or even months and was considered a sacred art,’ says Wikipedia.

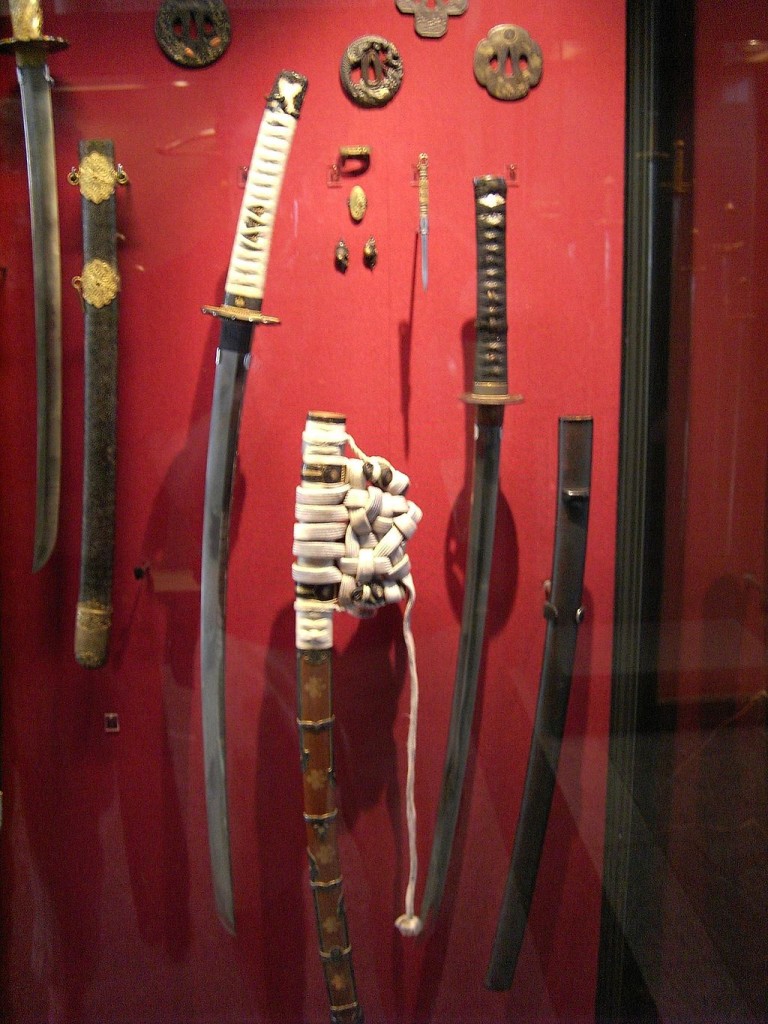

Traditional Japanese swords (courtesy Wikicommons)

Writing of the blacksmith in Bushido, The Soul of Japan, Inazo Nitobe commented, ‘Daily he commenced his craft with prayer and purification, or, as the phrase was, “he committed his soul and spirit into the forging and tempering of the steel.” Every swing of the sledge, every plunge into water, every friction on the grindstone, was a religious act of no slight import. Was it the spirit of the master or of his tutelary god that cast a formidable spell over our sword?’

Where did the religious reverence come from? Mircia Eliade was probably not the first to point out that metal as a gift of Mother Earth had a spiritual fascination for ancient humans. ‘The blacksmith and the shaman come from the same nest,’ runs an old Siberian proverb.

The extract below is taken from the magazine Sacred Hoop issue 86. In ‘The Spirit of the Blacksmith’ Nicholas Breeze Wood writes of the Mongolian-Buryat blacksmith spirit. Given the links of early Shinto with Siberian shamanism, the traditions of the Buryat Mongolians may help shed light on the special nature of the Japanese sword.

***************************************************

THE SACRED BLACKSMITH

In Hindu mythology, Tvastar, or Vishvakarma as he is sometimes known, is the blacksmith of the gods, whereas Vulcan (Hephaestus) holds that role in Greek and Roman mythology, using as he does a volcano as his forge. In ancient Irish mythology, the sacred smith is Goibhniu, and in Wales he is Gofannon. Both of these names mean blacksmith in their respective languages. In Anglo-Saxon Northern Europe, Wayland the Smith, who is known in Old Norse as Völundr, is the heroic blacksmith, who has many legends associated with him.

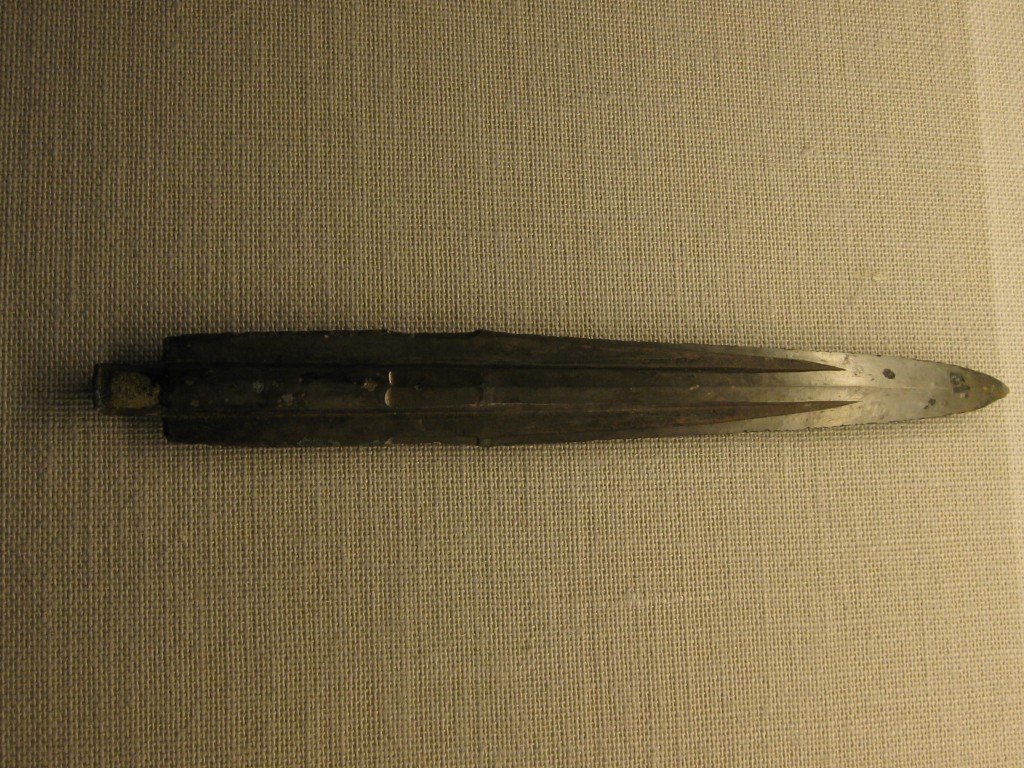

Yayoi sword (in Kokugakuin museum)

Traditionally in Siberia and Central Asia, the blacksmith is a very important person, closely related to the shaman; one Siberian saying is – ‘the shaman and the blacksmith are from the same nest’ – which sums it up well.

The blacksmith makes many of the shamans’ tools and pieces of equipment. He is the armourer of the shaman, and the iron objects fixed onto shamans’ coats or carried by them, are their armour and weapons. In Buryat tradition, such a smith and maker of shaman’s objects is called Dorligtoixun – ‘a person with Dorlig.’

According to Buryat legend, blacksmiths were taught by spirits from heaven called tengers, who were sent down to the earth to train human beings in the blacksmith’s art. They descended, carrying a hammer, tongs, and bellows ‘the size of a meadow’ to the peaks of mountains. The first people to be trained by the tengers handed down their skills to their descendents. Thus the role of smith became a hereditary one, generations of blacksmith families making the shamans’ ‘armour’, tools and weapons, being honoured for their work and their skill.

Iron was considered magical in its own right, but the smiths worked with other, non-ferrous, metals too. These smiths, like shamans, are divided into two groups: ‘white’ and ‘black.’ Blacksmiths generally forge articles from iron, the ‘black metal’, and their work includes domestic items, such as axes, knives and parts for horses’ harnesses, as well as shoeing horses. They also make the shamans’ items related to Damjin Dorlig such as metal parts for the shaman’s costumes, and iron parts for drums.

White smiths are those who tend to work with non-ferrous and precious metals, and their shamanic work would include making brass and bronze ritual mirrors, and the casting of amulets and bells.

Japan's imperial regalia, as described in the mythology