Today is August 15, which is the day of Japan’s surrender in WW2. It is also the day that in recent years government ministers have visited Yasukuni to pay respects to the war dead (including 14 Class A war criminals enshrined in secret in 1978). However, I’m happy to announce that no government ministers are visiting the shrine this year as the DPJ wishes to distance itself from the confrontational politics of the previous LDP. It’s a great victory for common sense. And, I believe, for Shinto.

The issues surrounding Yasukuni are complicated, but the central issue is that it acts as a symbolic space for extreme nationalism in Japan. The religious aspect is subsumed in the political, as indeed it has been since the shrine’s predecessor was founded in 1869. The well-known scholar John Nelson (‘A Year in the Life of a Shinto Shrine’ / ‘Enduring Identities’) gave a talk in 2006 at Otani University here in Kyoto, where he showed an educational documentary he has made about Yasukuni Shrine. It covered the following points:

A symbolic gathering spot for nationalists

* Yasukuni was an ‘invented tradition’, set up at the start of the Meiji era. It was a deliberate ploy by the new government to further the interests of state, and as such it was never a regular Shinto shrine. (Still today it is not part of Jinja Honcho.) Shinto ritual was merged with Buddhist concern for the dead and wedded to a newly constructed notion of imperial symbolism, so that only those who died for the emperor were glorified as kami. For the first time in Japanese history, the emperor went to give thanks to the souls of commoners. It was an entirely new form which differed from traditional kami worship and from Shinto-Buddhist syncretism. [In the Kojiki and Nihon Shoki it is the souls of enemies which are enshrined.]

* The shrine is based on the notion of restless spirits, prevalent throughout East Asia and fundamental to shamanism. The Meiji idea was that those who died for the emperor, often young and in terrible circumstances, would come back to plague the living unless constantly pacified. At the same time the families of those who died would gain consolation from their divinity. According to the shrine, the war criminals enshrined secretly in 1979 also gave ‘meritorious service’ to the emperor. Since that year however there have been no imperial visits and information disclosed in 2006 indicates the emperor clearly disapproved (as it seems does the present emperor).

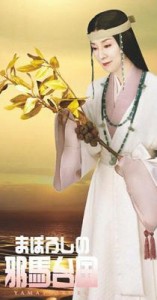

Prime minister Koizumi making a strongly political point

* In the run-up to WW2 Yasukuni acted as a symbolic space for ultra-nationalism. Now it still continues to act as a symbolic space for nationalists and the far right. Amongst those attached to the shrine are such groups as the All Japan Association which portray Japan as an innocent victim in WW2. The shrine acts as a rallying point for those seeking state sponsorship of Shinto, which is why the prime ministerial visits of Koizumi were so alarming – the initial step on a slippery slope towards reinstituting prewar ideology. Japanese opponents to the visits included left-wing groups, Christian organisations, liberals and internationalists.

* The Bereaved Families Association wants the prime minister to visit Yasukuni in the same way that the American president visits Arlington. However, whereas all religious groups are free to commemorate the dead at Arlington, only Shinto priests can do so at Yasukuni. A more proper equivalent to Arlington would be the Chidorigafuchi National Cemetery. Several leading politicians have spoken out in favour of making it the national focus, rather than Yasukuni, but the LDP vetoed funds for a secular cemetery.

* Yasukuni’s status as a religious institution has been disputed legally. In 1988 a case of interest concerned a woman in Hiroshima whose Self-Defence Force husband died in an accident. He was inducted into the kami. The wife, a Christian, strongly objected and took the shrine to court. The Supreme Court verdict in 1988 was that the woman did not have a case since it was a matter of religious toleration. Some think the judgement hangs uneasily with the Japanese constitution that stipulates separation of state and religion.

* Objections by other Asians, such as Chinese and Koreans, to the war glorifying, one-sided view of history presented in the Yashukan museum have been ignored. (There is no mention of Japanese atrocities, and the focus throughout is on the splendid sacrifice of Japan’s youth for the emperor.) However, when the museum’s exhibit about Japan being unjustly pressured into war by the US was taken up by influential Americans such as Henry Hyde, concessions were made and the exhibit amended.

* In all, over there are over 2,466,000 enshrined kami (including 27,863 Taiwanese and 21,181 Koreans).

Chinrei-sha, a small boxed area within the precincts, is dedicated to other war victims, including opponents of the emperor. Untll 2006 it was boarded off and could not be visited.

Yasukuni functions too as an ordinary shrine with prayers for the dead

(the above photo courtesy of keito at http://thetalkingtwenties.wordpress.com/2010/03/24/college-field-trip-understanding-yasukuni-jinja-tokyo-japan/)

;

;