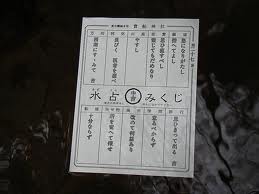

The ofuda is the equivalent in the house of ‘the spirit body’ (goshintai) in the Shinto shrine. The word literally means an honourable tag or tablet, and it is usually purchased from a shrine. It acts as a symbol of the kami, and can be understood as containing the same essence. Placing an ofuda in the household altar (kamidana) is thus to welcome a spirit into the home. It’s as if it were a candle alight with the same energy as that in a Shinto shrine.

The ofuda consists of a piece of wood or a card upon which is written the name of the kami, or sometimes the name of the shrine. A ritual is performed which charges the ofuda with the power of the kami. It is as if something of the divine is transferred into it. In this sense the ofuda is sacred and should be treated with care. On no account should it be removed from the paper covering in which it is wrapped. Like a battery, it only has limited power and needs to be replaced each year.

The Association of Shinto Shrines recommends that three ofuda be placed in a household altar. These include one from Ise Jingu where Amaterasu is enshrined; one from a regional shrine that the worshipper frequents; and one from the ancestral shrine (ujigami) to which the family is attached. In the case of a single-doored kamidana, the ofuda are placed in the following order: that of Amaterasu goes on top, that of the ancestral shrine in the middle, and that of the local shrine at the back. If the household altar has three separate doors, however, then the ofuda of Amaterasu should occupy the centre, that of the ancestral shrine the right, and that of the regional shrine the left.

Adherence to the above is not common in practice, and many Japanese simply use ofuda from their favourite shrines. These are changed annually, usually around New Year when they are taken to the shrine where they were purchased and ceremonially burnt. In their place new ofuda are purchased and put in the kamidana (or simply attached to a wall). Those who do not live within reach of a shrine should make sure to replace their symbolic ofuda with a new one. For those who live abroad, it may be possible to obtain them through the post (those in the US may apply to http://www.tsubakishrine.org/). Where this is not a viable option, consideration could be given to creating one’s own.

(The above was written in conjunction with Timothy Takemoto of the Shinto Online Association, who provided the visuals. See http://nihonbunka.com/)

A British observer in the early 1860s recorded an interesting encounter in his diary. He and some other foreigners were traveling though the streets of Edo (Tôkyô). As they neared a public bath, someone inside the bath noticed that exotic foreigners were in the vicinity and let the other bathers know. They all came running out of the bath house, completely naked, to look at the British travelers, who no doubt did some staring of their own. According to the diary: “Men and women were all bathing together. They all came running out of the bath hut to gawk at us as we passed by. Not a single one made any attempt to cover up. They were like Adam and Eve before the fall, appearing to us just as they had been born”

A British observer in the early 1860s recorded an interesting encounter in his diary. He and some other foreigners were traveling though the streets of Edo (Tôkyô). As they neared a public bath, someone inside the bath noticed that exotic foreigners were in the vicinity and let the other bathers know. They all came running out of the bath house, completely naked, to look at the British travelers, who no doubt did some staring of their own. According to the diary: “Men and women were all bathing together. They all came running out of the bath hut to gawk at us as we passed by. Not a single one made any attempt to cover up. They were like Adam and Eve before the fall, appearing to us just as they had been born”