A Mighty Megalith

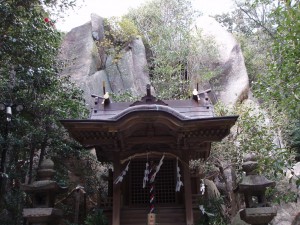

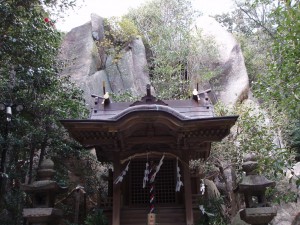

Small but potent is how you might describe Koshikiiwa Jinja. It’s not one of Kansai’s famous shrines. Located on a hill at Korakuen, it’s an appendage to the grander Nishinomiya Shrine and enshrines the same deity: hence its other name – Kita no Ebisu.

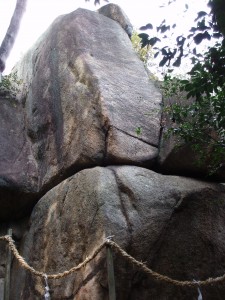

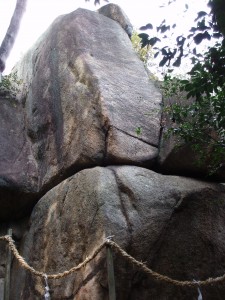

Despite the relative obscurity, Koshikiiwa is a place of intriguing folkore. The shrine’s origins are unknown, though there’s thought to be a reference to it in the Engishiki (927). The prime feature is an iwakura sacred rock, worshipped since time immemorial. The megalith is ten meters high, with a circumference of thirty meters. Walk round it clockwise in traditional fashion and you get a sense of the solidity.

The name Koshikiiwa translates as ‘Rice Steamer Rock’ since it was thought to resemble a traditional cooking vessel used in the making of saké. Rice in Japan is closely connected to fertility, which explains why the rock supposedly promotes pregnancy and protects childbirth.

The most famous anecdote about the rock connects with its rice steamer name. In the 1580s under Hideyoshi it was earmarked for use in the construction of Osaka Castle. Perhaps the idea was to bolster the castle’s defences with the protective magic of a sacred rock. Marks can still be seen that were made at the time, including a seal set into the rock to signify it was destined for the castle.

When Hideyoshi’s men came to cut the rock into pieces however, it emitted a poisonous gas that overcame them and they had to abandon the idea. The story suggests pressurised heat trapped beneath the surface, and perhaps there’s a folk memory of volcanic forces at work. Indeed if you examine the rock you’ll find a mysterious crack as if the result of compressed energy.

Rock worship

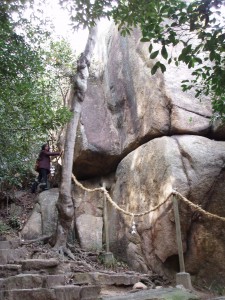

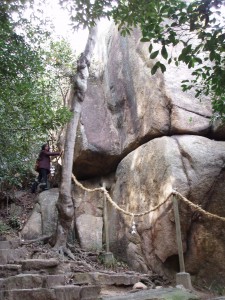

Further up the slope from the giant rock is an outcrop named Kitanokura, which could be translated as North God Sitting Place. The association of rocks with gods is strong in Japan, and some serve as goshintai (holy body) for the kami as in this case. If you ask shrine priests about the rock worship, they’ll simply tell you it’s an ancient custom and leave it at that. But what is the thinking behind it?

Coming from Britain, I’d always assumed rocks to possess an elemental force. The standing stones of ancient Briton are said to resonate with energy, as if they are antenna that pulsate with the natural rhythms of Mother Earth. Moreover, the solid structure of Stonehenge speaks of a desire for durability in a transitory world that was fragile and insubstantial. It was a true ‘rock of ages’ to which the people of the past could turn for comfort.

In Japan something similar seems to have occurred, with rocks closely associated with the realm of the dead. This probably arose through burial practices on mountain sides or in tombs, whereby the spirit of

the deceased was thought to be absorbed into the rock. The unchanging nature of the rock-spirit world contrasted with the perishable world of the human-vegetable world.

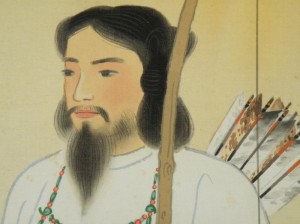

In Kojiki (712) Japan’s creator-god Izanagi visits the underworld to see the deceased Izanami but is repulsed by her rotting body and chased out. As he hurriedly exits the spirit realm, he shuts off the opening with a large boulder. The rock thereby became a visible marker of the spirit realm. Over time such rocks became symbolic ‘seats’ or ‘bodies’ through which spirits manifested themselves, and in Japanese mythology one finds the kami descending to earth in mysterious ‘rock boats’.

No doubt the reverence for rocks was reinforced by the palpable sense of presence that some of them possess. This may be the result of sheer immensity, or a peculiar shape, or a striking location, or simply an undefinable numinous quality. For the ancients such rocks were far more than physical mass; they were gateways to the spirit world.

Shrine features

Though the rock of Koshikiiwa is the shrine’s pride and purpose, there are other items of interest too. It may strike some as odd, for example, that the main kami was installed by a Buddhist priest, but this was in 1656 back in the good old days before Buddhism and Shinto were artificially separated. It was shortly after the refounding of the shrine, though the elegant buildings that one sees now are relatively recent: the Honden was rebuilt in 1936, the Haiden in 1983.

In the grounds there’s a sumo ring in which a tournament is held in mid-September, and a stage on which Takigi Noh is performed on September 21 each year (the Danjiri festival is held on the following two days). The shrine also boasts flowering shrubs like camelia and a rare ‘prefectural treasure’ called Himeyuzuriha that blooms in March. (Rather touchingly, when I went in late March there was a sign to apologise for the early end of the flowering season due to the unseasonal warm weather.)

As you pass along the sando leading to the shrine, take some time to look at the notice boards that stand on either side. Religious poems are juxtaposed with children’s drawings and newspaper items. There

are also archaeological articles in which one learns that the shrine is aligned towards the top of Mt Kitayama, that outlying rocks are aligned north-south and east-west, and that beyond the shrine is a split stone that points towards the sunrise on the winter solstice and sunset on the summer solstice.

It’s fascinating stuff, and it makes one ponder how the people of the past were better attuned than we are to the wonders of the universe. For Joseph Campbell, the genius of mythological studies, Shinto is essentially a religion of awe and the monumental rock of Koshikiiwa is a prime example. It’s worth spending a few meditative moments in the shadow of the mighty megalith to get a sense of what that truly means. Who knows? In the heart of the rock you too may find the voice of the kami.