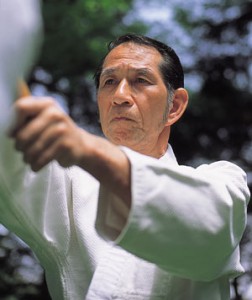

Higuchi sensei of Takemusu Aikido Kenkyukai

I’ve never been drawn to martial arts, but intrigued by the Shinto connections of aikido I decided yesterday to go along to a talk put on by the Kyoto Prefectural International Center. It could be argued that the spread of Shinto abroad owes more to aikido than any other single factor, so I was naturally curious to learn more. It was a horribly hot and humid day, which may explain why I was the sole member of the audience. Lucky me: I got my own private demonstration.

The session started off with an analysis of the Chinese characters for aikido: meet – ki (or chi) – way. Way of harmonising ki. The analysis revealed that there was a moral component of helping one’s enemies, as if bending them back onto the straight and narrow. There was then a brief demonstration on tatami with a woman throwing her opponent this way and that. It reminded me of Steven Seagal shows I’ve seen on Youtube that looked patently fake, with attackers flinging themselves in various directions rather than actually being thrown.

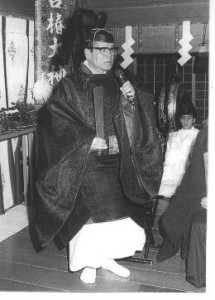

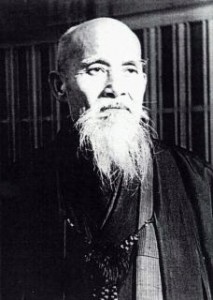

Aikido founder, Ueshiba Morihei

The demonstration was followed by a 25 minute black-and-white film produced in 1961 featuring aikido founder, Ueshiba Morihei (1883-1969). It showed practitioners at his dojos, as well as midnight training on a mountain. The swirling patterns and constant turning had an almost hypnotic effect. There was one scene in which an opponent was held down by a single finger, and a dramatic finale in which a genuine sword was used in a test of a pupil’s ability.

At the end I was able to ask questions, and the sensei gave me to understand that the spiritual aspect was crucial to the true nature of aikido and that without it the practice would be purely physical, much as yoga has become decoupled from Hinduism. Though Ueshiba had taken inspiration from Shinto, it wasn’t necessary to be a Shintoist as long as one developed one’s spiritual side through self-discipline, honesty and respect for others.

For the final few minutes I had to take the mat and was expected to sit seiza, which unfortunately I can’t do because of an industrial accident damaging my knee bone. On the whole it’s not a big problem, but in Japan not being able to do seiza has proved a major handicap, effectively debarring me from the tea ceremony for instance. Did it mean it was impossible for me to do aikido? ‘Muri dewa nai….’ (not impossible) the sensei replied, but left the sentence dangling ominously.

Crosslegged, I was able to engage with one of the group’s members who showed me how to deflect pushes. I got my first practice in the use of ki, with the admonition I needed to be more ‘sunao’ (honest, receptive). It was something to do with harnessing the natural flow of energy. After being thrown off-balance a few times with a flick of the wrist, I suddenly realised something: those guys in the demonstration sessions weren’t faking at all!!

The relationship of aikido to Shinto is a fascinating subject and raises the issue of Shinto’s influence on martial arts in general. But that is a matter for a separate post… .