‘The Meaning of Shinto’ by J.W.T. Mason Canada: Tenchi Press, 2002 179 pages. ISBN 155369139-3 $17.00

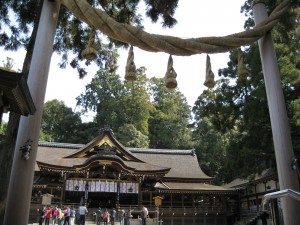

This is a reprint of a 1935 publication by a respected writer on spiritual traditions. The foreword is by Ann Llewellyn Evans, priestess at Bright Woods Spiritual Centre & Kinomori Jinja in British Colombia, who was responsible for the reprint. One can understand the need for republication. As well as explaining the philosophical basis of Shinto, Mason makes a forceful case for its universalism. His main emphasis is on life as a divine self-creative development, a monist belief that he thinks the West would do well to learn from. Much of the book is concerned with interpreting Kojiki mythology and early history, though there are also sections on modern times and the influence of Shinto on Japanese culture in general. The writing is at times abstract and repetitive, yet for the reader who perseveres there is much rewarding material.

The book is remarkable in a number of ways. Firstly for the sensitive way in which Mason unpacks Shinto. Secondly, for the way in which he places it at the centre of Japanese culture, more or less at the exact time as Suzuki was doing the same thing for Zen (Zen and Japanese Culture was first published in 1938). Suzuki’s book went on to become hugely influential in the spread of Zen to the West; by contrast Mason’s book was little known.

Quote follows: “Shinto’s ‘narrow nationalism’ is due to the fact that it began as an explanation of the history of the Japanese race’s origin and early development, and expresses its intuitive knowledge of reality in terms of the Japanese nation. This, however, is fundamentally no more than a method of presentation. Everything that is basic in Shinto can be explained in ways applicable to the universe, not only to Japan. ‘Narrow nationalism’ is not Shinto because Shinto is universal in its concepts. Those who interpret Shinto as being limited to Japan in its comprehension of life do not understand Shinto.” (p.177)

“Those who interpret Shinto as being limited to Japan in its comprehension of life do not understand Shinto.” I wish Mason was still alive: he’d be able to put a few people straight! You can’t help wondering how the ideas would have been received by Mason’s Japanese friends. His epitaph for instance was written by Inoue Tetsujiro, an imperialist who argued that Christians were traitors to the national ideology ( though he was beaten very badly by fanatics – he lost sight in one eye – because he wrote that the imperial jewels were replicas, the genuine items having been lost at sea when the emperor Antoku drowned after his ship was sunk in the 12th century.)

In response to my enquiry on the H-Japan mailing list, John Breen posted a short piece about Mason as follows:

“Thanks to John Dougill for his posting on Mason and Shinto. I don’t know much about the man, but I did write a short piece on him. Mason, an American who worked as the New York correspondent for the Daily Mail for a while, wrote numerous books and articles on Shinto in English and in Japanese. His main argument seems to have been that Japan owed its successful modernisation to Shinto, and this because Shinto guaranteed the freedom of the individual and encouraged individual endeavour to a degree which Western philosophy could not. The key was the Shinto teaching that the spirit of the kami resided in all of human kind. As you say, John, Mason regarded Shinto as being nothing less than the key to the further development of civilisation.”