A month has passed since New Year, so I was surprised to find Shimogamo bustling with visitors despite the cold of a 7C afternoon. There has certainly been a noticeable upturn in numbers and the reason is not hard to discern. It is one of three shrines recently highlighted on television as one of the few places in Kyoto to worship at a subshrine to the dragon, this year’s Chinese zodiac animal.

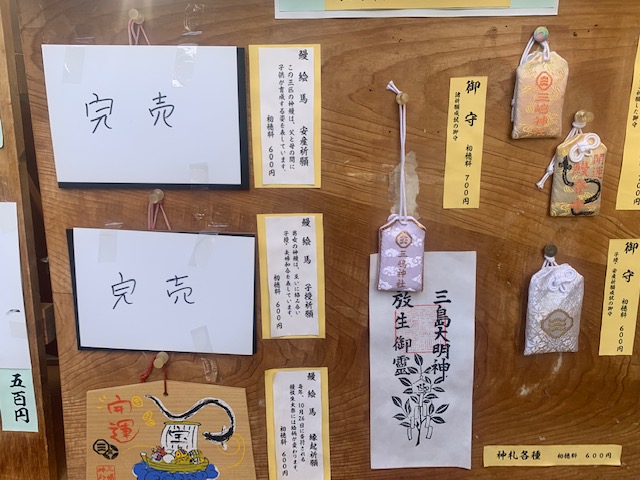

Watching the various activities and jolly atmosphere brings to mind questions about whether it is all religious in essence, or simply a custom, or even just superstition? The answer is far from clear. On the one hand is the sheer number of people evident on such occasions, nearly all of whom pay respects, toss a monetary offering into the collection box, and buy an amulet or votive plaque (ema). On the other hand there are surveys that suggest that only five percent or less actually “believe” in the kami to which they are nominally praying. More often than not, worshippers have no idea of the name of the kami.

In Western terms a parallel can be found in the celebration of Christmas. In the UK for instance, nearly everyone takes part in some kind of festive activity, yet few would claim to be practising Christians. Indeed, for many if not most the celebration has nothing to do with a belief in Jesus or God. It is more a matter of custom, shaped by the culture in which it takes place.

So it is that certain things are taken for granted by Japanese visitors to a shrine. It is customary to wash your hands before entering the compound as a symbolic purification of body and mind. It is customary to pay respects by bowing as you enter through the torii. It is customary to make an offering, however little, and it is customary to give thanks to the presiding kami. It is customary too (though not obligatory) to purchase a protective amulet or other goods from the shrine office.

Behind the Japanese shrine visits lies a strong respect for tradition and ancestry. The custom of kami worship has been practised for over a millennium, though standardisation only came after the Meiji Restoration of 1868. Participation in shrine visits is not so much about kami worship, however. It is more a matter of communal compliance, fosgtered by a sense of belonging and what it means to be Japanese.

Post-shamanic cultures take their form from the role of the shaman in ancient times. It involved not only contacting the spirit world, but preserving the tribal identity by knowledge of the history and mythic past. Shinto shrines perform a similar role, for the annual round of festivals and rituals honour the way of those who came before. How appropriate then that this year should be the turn of the dragon. Living in the watery depths, the mythical creature has wings which allow it to soar into the high sky. In this way it unites heaven and earth, a messenger from the gods and ancestral spirits that guide Japan even into the present day.

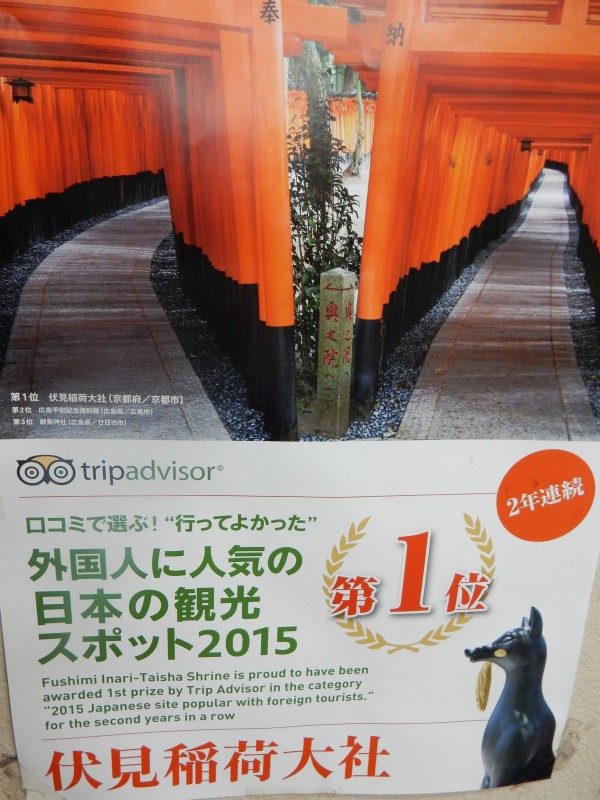

On Sunday I took an out of town visitor to a combination of Tofuku-ji Zen temple and the popular Fushimi Inari shrine. They are both in the south-east of Kyoto, a mere twenty minutes walk apart, and the Zen-Shinto combination makes a wonderful introduction to the world of Japanese religion. The large solemn buildings of Zen provide a contrast with the colourful bustling crowds at Fushimi, and yet the similarities are striking.

On Sunday I took an out of town visitor to a combination of Tofuku-ji Zen temple and the popular Fushimi Inari shrine. They are both in the south-east of Kyoto, a mere twenty minutes walk apart, and the Zen-Shinto combination makes a wonderful introduction to the world of Japanese religion. The large solemn buildings of Zen provide a contrast with the colourful bustling crowds at Fushimi, and yet the similarities are striking.