These extracts are part of an ongoing series from a forthcoming book about travelling from the most northerly station in Japan to the most southerly.

***********************

Kunchi refers to the lively festivals of north Kyushu. Karatsu, Nagasaki and Hakata (Fukuoka) are the Big Three. Karatsu in particular is famed for its elaborate floats, made of layers of paper maché. At the museum, fourteen of them were lined up in a large hall, along with explanations, and I was quietly making notes when a middle-school excursion arrived armed with questionnaires. Suddenly the hall was as busy as a bee hive, with students rushing hither and thither to fill in answers and get to the ice cream shop.

If the students had allowed themselves time to stop and stare, they would have seen how wondrous were the paper maché creations. From the depths of an artist’s imagination were conjured up mythic monsters, auspicious animals, historical heroes. My favourite was the head of a drunken demon, which had bitten into a samurai’s helmet and been beheaded as a result.

At one end of the hall was a large screen showing previous festivals in which the floats, weighed down by people inside and on top, were hauled along by inebriated men. Musical accompaniment was provided by drum, bell and flute. Moving slowly at first, the teams suddenly surged forward, then broke into high-speed cornering that was positively life endangering. Were it not a tradition, it would surely be banned.

**********************

At the heart of Shinto’s annual festivals are portable shrines (mikoshi) which contain the kami. The heavy wooden mikoshi are usually borne on the hardened shoulders of men, but in this case the three kami arrived on the back of small vans. Men in happi festival jackets waited to unload them, then took up position sitting along three sides of a square. At the front was a temporary altar.

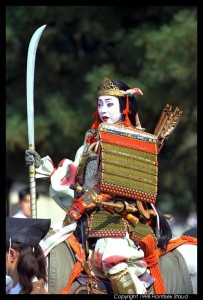

Participants were dressed in a colourful array of costumes: four priests in purple robes; miko dancers in red and white; child flautists in blue kimonos; and taiko drummers in all-white, their sleeves tied back for action.

But the undoubted star was a chigo (sacred child) in embroidered kimono and golden crown. (In former times, the chigo served as unpolluted vessel into which the kami descended, a remnant of Shinto’s shamanic roots.)

The opening ritual included purification, offerings, a norito (formal prayer), a sacred dance, and a stunning taiko performance. Then the three mikoshi were loaded onto trucks again, each followed by a troupe of attendants. I tagged along behind one of them. The musicians played festival tunes, there was much shouting and saké was passed around. This was religion as celebration, and all around were smiling happy faces.

Unexpectedly an argument broke out, and men were yelling at each other, even grabbing each other’s jackets. It looked like a confrontation between rival groups, and spirits were running high. But then all of a sudden, it came to an abrupt end. It was a feigned quarrel, and everyone was laughing.

One of the most appealing aspects of the festival is the authenticity of the costumes, which were made of material as close to the original as possible. Even the weaving and dyeing was done in the manner of the age they represent.

One of the most appealing aspects of the festival is the authenticity of the costumes, which were made of material as close to the original as possible. Even the weaving and dyeing was done in the manner of the age they represent.

To convey their delicate feelings the aristocrats used verse as a means of expression, in particular the short poetry form known as waka. This was based on a 5-7-5-7-7 syllable pattern (haiku was formed later by dropping the last two lines). Topics ranged from nature appreciation through the whole gamut of love found and lost.

To convey their delicate feelings the aristocrats used verse as a means of expression, in particular the short poetry form known as waka. This was based on a 5-7-5-7-7 syllable pattern (haiku was formed later by dropping the last two lines). Topics ranged from nature appreciation through the whole gamut of love found and lost. Since humans resonate in tune with harmony, runs his thesis, the poet can promote unity by capturing the ‘good vibrations’ in words. These were communicated to others through sound, for waka were not simply written words but meant to be chanted out loud. (Translated literally, waka means ‘Japanese song’ and the verse are referred to as uta, or songs.) You could say then that the poems are a form of harmony in more ways than one.

Since humans resonate in tune with harmony, runs his thesis, the poet can promote unity by capturing the ‘good vibrations’ in words. These were communicated to others through sound, for waka were not simply written words but meant to be chanted out loud. (Translated literally, waka means ‘Japanese song’ and the verse are referred to as uta, or songs.) You could say then that the poems are a form of harmony in more ways than one.