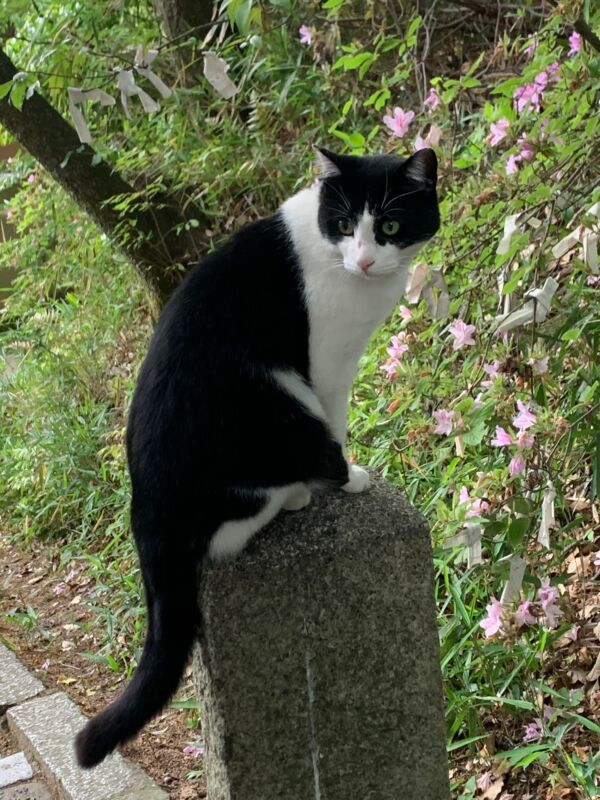

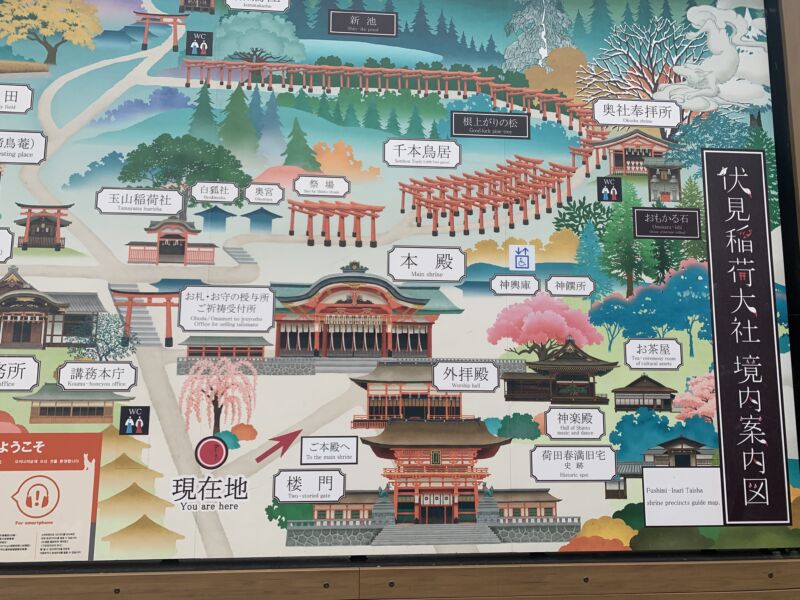

Fushimi Inari is the most famous of all the places associated with the immigrant Hata clan. Intriguingly the northeast of China from where the Hata might have originated had a fox clan in ancient times.

As part of Golden Week activities this year, I made a tour of places in Kyoto associated with the influential Hata Clan. Anyone who has lived in the city will have come across the name at some stage, as the clan were instrumental in the building of Heian-kyo in 794. Prior to that, they were responsible for the founding of Koryu-ji temple, Matsuo Taisha and Fushimi Inari amongst others.

Once a clan shrine for the Hata, Osake Jinja has seen better days but has managed to survive into the present.

Much about the Hata is shrouded in doubt because there are no reliable sources. It has given them an air of mystery, with some claiming they were Nestorian Christians and others saying they were descended from China’s Qin Emperors. There’s even a theory they were a lost tribe of Israel. The truth is probably less fanciful, but no less intriguing because of the many clues that remain.

The Hata came to Japan from Korea, though it’s believed they originated in China (their name is written with the same Chinese character as the Qin Emperors of old). They arrived in Japan in considerable number, and brought with them advanced techniques in silk-weaving, saké making, stringed instruments, agricultural methods, and large-scale landscaping. This has led some to suppose they had Silk Road connections, by means of which they picked up the leading knowledge of their time.

There are many places throughout Japan associated with the Hata, particularly along the migration route from Korea into northern Kyushu, along the Inland Sea to the Kobe area and then inland to the Kyoto basin. The place most closely connected with them though is the Uzumasa area of Kyoto (Uzumasa was a name bestowed on the clan leader by the emperor). There are a number of places with Hata origins, one of which is the small Osake Jinja, effectively a Hata clan shrine. Its noticeboard gives an overview of the clan’s developments (though this is quite different from the Wikipedia version).

In 356 (other reports place it much earlier) a Hata representative came to Japan to help avoid war with Paekche, one of the Korean kingdoms. This was followed by an influx of 18,670 people at the time of Emperor Ojin. They brought gifts of gold, silver and silk etc leading the Japanese authorities to look on them kindly.

Konoshima Jinja, built by the Hata, is more commonly known as Kaiko no Yashiro, the Silkworm Shrine, because one of its subshrines is dedicated to the deity.

In 471 Emperor Yūryaku bestowed the family name of Uzumasa on Hata Sake no kimi (or Hata Sakekimi) for his contribution to the spread of sericulture. The area of the Kyoto basin in which the clan came to settle was accordingly named Uzumasa (uzumoreru implies ‘being covered or buried in treasure’).

There may have been a clan shrine called Uzumasa Jinja, but at some stage this was destroyed and merged into Osake Jinja (named for Sakekimi), which has survived into the present. No doubt it was once a flourishing place, but now it is confined to a small roadside space housing a torii and small token shrine.

More impressive is another Hata shrine in the area, known as Konoshima Jinja (or Kaiko no Yashiro, the Silkworm Shrine). It’s thought that this was built around 603 as a protective shrine for the nearby Koryu-ji temple, put up by Hata strongman, Kawakatsu. The shrine is notable for a peculiar triangular torii, which stands near the Worship Hall, giving rise to fanciful theories about Christian connections (three sides representing the Trinity!). More about this in a later post.

In 701 Hata Imikitori founded Matsuo Taisha. He was out hunting one day when he saw a huge tortoise. In Chinese folk custom tortoises are a symbol of good luck and longevity. Sure enough, the turtle revealed a spring of fresh and invigorating water coming down from Mt Matsuo. As a result the shrine today is full of tortoise statues and noted for its saké connections (the water from its spring is used for brewing). (See here for more about about Matsuo Taisha.)

A turtle at Matsuo Taisha spouting water into the temizuya (water basin)

In 713 Hata Irogu was doing archery practice in the Fushimi area when his ricecake target turned into a white bird and flew up Fushimi Hill to reveal a field of rice. (See Fushimi Inari.) Later when Heian-kyo was built, Fushimi Inari became the protective shrine for the new capital’s Toji Temple.

In 794 the Hata clan played a decisive part in Emperor Kammu’s decision to move the capital from the cursed location at Nagaoka-kyo. The clan not only possessed much of the land in the Kyoto basin and were able to help fund the cost of relocation, but they were skilled too at handling the large-scale engineering involved, such as redirecting rivers and building earthworks.

(Hata clan descendants remain throughout Japan today, and there is an annual get-together for members. The Matsuo Shrine in particular is said to retain ties to the clan.)

The subshrine at Fushimi Inari dedicated to Hata clan ancestral spirits

The sacred rock (iwakura) for the spirit of Hata no Irobu, founder of Fushimi Inari

For Part Two of this series, click on this link for Hata Part 2: Kawakatsu.