Shirakumo Jinja

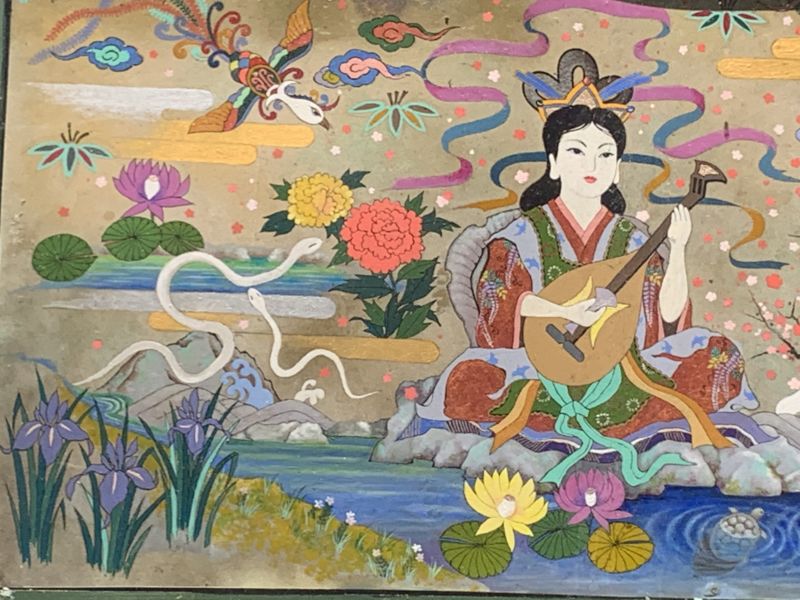

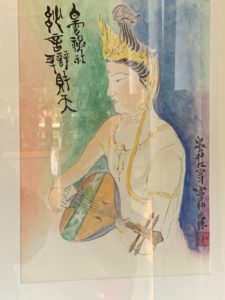

Shirakumo Shrine in Gosho, like the nearby Itsukushima Shrine, is linked with Benzaiten (also known as Benten). The reason, however, is different. Whereas Itsukushima Shrine stands on a small island, Benten being associated with water, Shirakumo Shrine is linked with the musical instrument she plays – the biwa.

The shrine stands on the site of the former Saionji residence, and the Saionji family were head of the Biwa School of music. The form of the deity worshipped is Ichikishima-hime-no-mikoto, a manifestation of Benten that was invited from Chikubushima Island in Lake Biwa (so named because the lake resembles the shape of the instrument).

The shrine has a long and complicated history. It originated in ancient times as a Buddhist temple dedicated to a manifestation of Benten known as Myo-Onten, or Myo-On Benzaiten. One of her worshippers was Fujiwara no Moronaga, described in The Tale of the Heike as a distinguished biwa player.

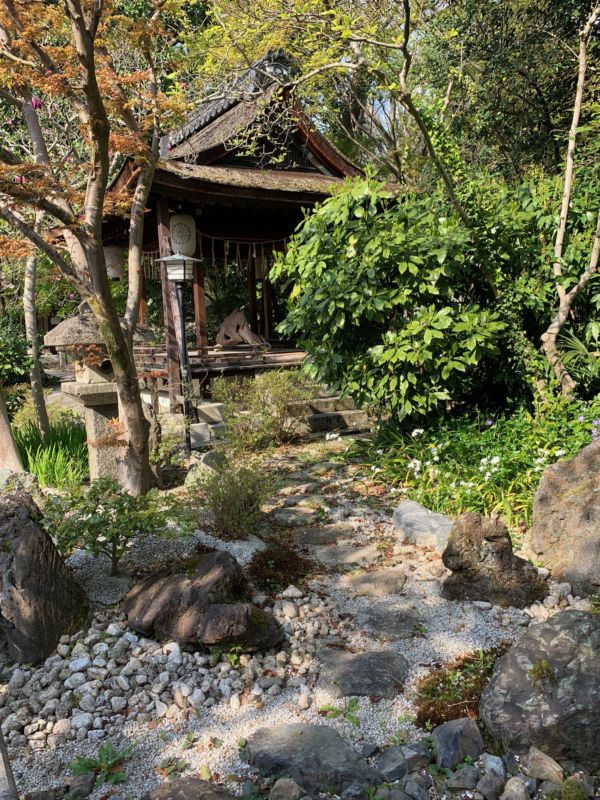

In 1224 the temple was situated where the Golden Pavilion now stands. Thereafter it suffered various mishaps before being moved in 1769 to its present position, within the grounds of the Saionji residence. After the Saionji family moved to Tokyo following the Meiji Restoration, the temple was re-dedicated as a shrine in accord with the law about the separation of Shinto and Buddhism.

In place of the syncretic Benzaiten, the newly enshrined deity was pure Shinto and the shrine took its name from Shirakumo village (I’ve been unable as yet to find the location or the connection). According to a noticeboard at the shrine it was here that Saionji Kinmochi, prime minister and friend of Emperor Meiji, founded a private academy in 1869 that became Ritsumeikan University.

Shirakumo means ‘white clouds’, and clouds in the Daoist tradition are symbols of good luck, which is why they are often seen in Chinese architecture and paintings. Because they fuse elements of water and air, as well as mediating between sky and earth, they were considered auspicious as yin and yang symbols. In addition, the Chinese reading of the kanji (‘un‘) is a homonym for ‘luck or fortune’, and white as the colour of purity is much favoured in Shinto – white snakes, white horses, white shide strips. The name of the shrine thus has potent significance.

Clouds might also be considered appropriate for a water goddess, and the shrine’s water reputedly has healing properties. This is augmented by a sacred rock with curative power that stands behind the Honden (Sanctuary). As elsewhere in Shinto, the idea is to rub the rock to absorb the energy, then to rub the part of the body that one wants to be improved or healed.

Shirakumo presides over five divine benefits:

* Music – musical ability, the arts, creativity

* Water – life, fire prevention, disaster prevention

* Knowledge – wisdom, scholarship, eloquence

* Wealth – riches, prosperity, victory

* Luck – good luck, health, long life

The shrine’s prized possession, not on display, is a seated image of Myo-On-Benzaiten, possibly dating back to Heian times. In 2012 it was designated an Important Cultural Property – the only Shinto statue of a deity to be so honoured.

*********************

This is the final posting in a four-part series about the three shrines of Gosho (Former Imperial Palace and Park in Kyoto). For Part One click here, Part Two here, and Part Three here.