(photos on this page by John Dougill)

The following is excerpted from a translation of the sixth chapter of Bruno Lewin s Aya und Hata Bevolkerungsgruppen Altjapans kontinentaler Herkunft Wiesbaden: Otto Harrassowitz, 1962 Studien zur Japanologie, vol. 3, translation by Richard Payne with Ellen Rozett (Pacific World, New Series, No. 10, 1994)

One of the most wide-sweeping impacts on folk Shinto was the Inari cult initiated by the Hata, which consists of the worship of the deities of the crops. The point of origin of the cult was the Inari Shrine, in the District of Yamashiro and situated in the territory of the old royal domain of Fukakusa. Concerning the establishment of this shrine, the Yamashiro-fudoki reports:

Hata no Kimi Irogu, a distant ancestor of Hata-no-Nakatsue no Imiki, had amassed rice and possessed overflowing wealth. When he made a target (for archery) from pounded rice, this transformed itself into a white bird, which flew up and alighted atop a mountain. There it again became rice and grew upward. Inenari (“becoming rice”) is given therefore as the shrine’s name.

In addition the Jingi-shiryo clarifies this, saying that Irogu, moved by this wonder, in the fourth year of Wado (711) erected a shrine there and worshipped the transformed rice plant, on account of which the shrine was called Inari « inenari. Accordingly, the shrine is of a comparatively late date, though there can be no doubt that the Hata as long-standing cultivators of rice had long possessed the cultic worship of the rice gods, but now mixed with the cult of Inari shrine worship of the Japanese food deity Ukemochi-no-kami. In the Inari shrine the deities Uka-no-mitama-no-kami, Saruka-biko-no-kami and Omiya-nome-no-mikoto are worshipped. Uka-no-mitama is the main deity of the shrine, identical with Ukemochi.

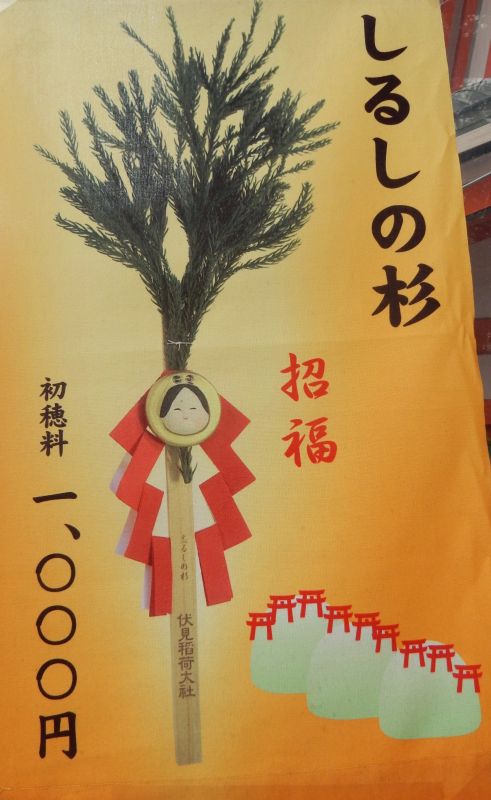

During the middle ages, the worship of the rice and food deities in the Inari cult spread over the whole of Japan. One can still count about 1,500 Inari shrines, most of them small field and village shrines, in which the fox whom one frequently comes across in the fields, is also worshipped, either as messenger of the deity or even as an incarnation of the deity itself.

The Inari shrine of Fukakusa is considered to be the mother shrine of all of these cultic sites. Its priesthood descended without exception from the prosperous Hata families of the surrounding area. From the Heian era the priests have borne the status name of Hata no Sukune . Gradually there separated out from amongst them more branch families: the Nakatsue, Nakatsuse , Onshi, Matsumoto, Haraigawa, Yasuda, Toriiminami and Mori.

The Inari shrine forms a triangle with the shrines of Kamo and Matsuno’o, in the middle of which was placed the final capital, Heian kyo. All three cultic sites enjoyed the support of the Imperial palaces and were visited in the course of history again and again by individual emperors to venerate the divinities there. The integration of the Hata with the history of these powerful shrines shows what a prominent position they possessed in the territory around Heian kyo. We can well assume that Kammu-tenno, in shifting the capital, allowed himself to be guided by the effort to remove himself from the immediate of the Yamato aristocracy and to lean instead on the rich and loyal, though politically unambitious, Hata clans.