(photos by John Dougill)

Mythological mystery

There are many fascinating mysteries in Japanese mythology, and one in particular has intrigued Green Shinto for years. Why would the heavenly deities choose to descend on Mt Takachiho in the south of Kyushu? Out of the hundreds of mountains available to them, why choose that one? (The mountain should not be confused with the town called Takachiho in northern Miyazaki, which also claims mythological links.)

The question is all the more vexing given the standard interpretation that the present imperial lineage ‘descended’ from Korea across the Sea of Japan. The boat journey from Busan to Hakodate has some convenient islands along the way at which to stop and refuel, notably Tsushima and Ikijima, so one can easily imagine how in ancient times it offered a convenient means of passage into Japan.

But if the ancestors of the imperial family came by this route, why would the mythology have them arrive at the other end of Kyushu? It’s all the more strange when one considers that there are taller mountains in Kyushu, such as nearby Mt Karakunidake, from which it’s possible to see the Korean homeland (indeed, karakuni is an alternate reading of the kanji for Korea).

To find out more, I made a trip some years ago to Takachiho to investigate the tenson korin (heavenly descent by Amaterasu’s grandson Ninigi no mikoto). There’s a shrine at the base with flat land called Takachiho-gawara where Ninigi no mikoto is said to have arrived, though one presumes this is simply the convention of establishing shrines on the lower slopes of mountains onto which kami descend. (In this way the place of worship is not only made accessible to villagers, but the sacred mountain behind it offers a focus for prayer.)

When you climb Takachiho, which at one point has a narrow ridge with sheer drop, you find Ama no Sakahoko (heavenly spear), a trident stuck into the summit. According to legend, Ninigi no mikoto supposedly thrust the three-pronged spear into the ground on his arrival from heaven (Takamagahara). How long it’s actually been there no one seems to know for certain, though Sakamoto Ryoma mentioned it in letters in 1866. Nonetheless, the question remains as to what exactly prompted the heavenly deity to descend on this particular peak.

Kuroshio

The first Europeans to step on Japanese soil arrived in 1543 in the form of two (possibly three) Portuguese merchants aboard a Chinese junk. The ship was making its way along the coast of China for trading purposes when it was blown off course by a vicious storm, during which it was badly damaged and no longer able to steer a course. Left to drift with the prevailing current, it was deposited in a welcoming bay in the island of Tanegashima. In this way, through the whims of the weather, history was made. (A model of the Chinese junk stands today on the headland where the boat was stranded.)

The current that brought the Europeans to Japan is known as Kuroshio. It flows from the east coast of the Philippines, past Taiwan and along the east of Japan to merge into the North Pacific. It is to the Far East what the Gulf Stream is to Europe, sending a steady flow of relatively warm water northwards to dissipate in colder seas. In this way the west of Britain and the east of Japan benefit from clement conditions and an enriched marine life.

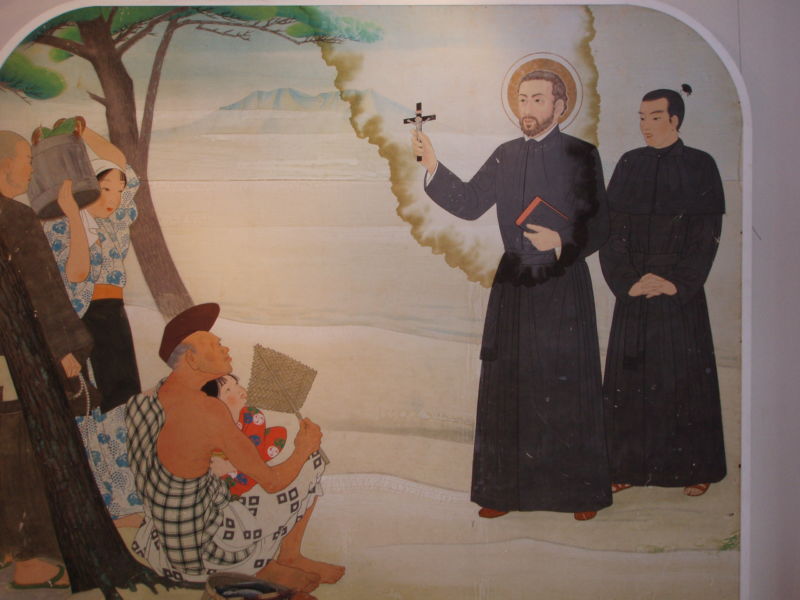

Six years after the arrival of the Portuguese merchants, Francis Xavier arrived in 1549. He had set out from Malacca on a Chinese junk, not particularly seaworthy, and the boat followed the Kuroshio current past Tanegashima into Kinko Bay in southern Kyushu to where the town of Kagoshima stands opposite the volcanic island of Sakurajima.

Following in Xavier’s wake, I took the modern-day jetfoil from Tanegashima to Kagoshima. On the way it passes Cape Sata on the southernmost tip of Kyushu, and once round the headland there come calmer waters as the ship enters the long expanse of Kinko Bay, extending inland for twenty-five miles. Lined with rocky sides and wooded hills, it makes a welcoming backdrop to arriving boats, and in the distance at the end of the bay stands a large mountain – Mt Takachiho.

Given the position of the mountain, it seemed that here was an answer to the puzzle as to why the heavenly deities had picked out Takachiho. In ancient times boats setting out from the east coast of China would have been drawn by the Kuroshio current towards Kyushu and Kinko Bay. And if they had settled in the area, it would have been Chinese custom to take the ‘mother mountain’ as their tutelary guardian. Rather than ‘descending’ from Korea, the mythical incomers would have arrived from Eastern China.

Mythological support

The mythical origins of Japan are set out in two books in the early eighth century, Kojiki (712) and Nihon shoki (720). By general consent, the former was a glorified piece of propaganda to provide emperors with divine status. The latter, with its alternative versions of events, was considered more like an official history. (For more on this topic, see here.)

For the following reading of the mythology, I’m indebted to the scholar Robert Wittkamp, who has sought to explain why the Nihon shoki has two books but the Kojiki only one. His supposition is that in contrast to the single imperial dynasty spelt out in the Kojiki, the Nihon shoki seeks to draw a distinction between the Takami Musuhi line in Book One and the Amaterasu line of Book Two.

Given this lineage break, it would seem quite possible that the Yamato dynasty integrated into their Korean tales the memory of an earlier ‘descent’ onto Kyushu. It is common after all for clans and tribes to mythologise their first arrival on foreign shores, and you find this in Okinawa for example with Kudaka Island claimed as the arrival point of the Ryukyu people and sanctified by the wonderful Sefa Utaki.

It may well be then that following immigration from Korea, the stories of descent onto Takachiho were conflated with the mythology of the sun going into hiding. It was through the creative work of Hieda no Are and O no Yasumaro (d. 723) that the competing stories were skilfully woven together into the Amaterasu myth as we know it today.

Following the compilation of the myths and legends in the early eighth century, the Kojiki story was largely disregarded in favour of Nihon shoki. It was only a millennium later with the Kokugaku Movement of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries that Kojiki came to be regarded as of wider significance. With the establishment of State Shinto under the Meiji government, the fictions of the concocted mythology were regarded as fact, and Takachiho along with spurious graves of early emperors treated as sacred ground.

(In Part Two a suggestion is made as to who might have actually ‘descended’ onto Mt Takachiho.)