Spanning the divide between the seen and unseen worlds

I happened to come across a short piece today that was a stark reminder of just how intertwined Shinto once was with Zen and other forms of Buddhism. It’s been nearly 150 years since the Meiji-era split between the religions, and we’re used to thinking of them as completely different. We talk of temples and shrines, of buddhas and kami, of foreign and indigenous, constantly reinforcing the division between them. Yet for so much of Japanese history this was far from the case, and in most people’s minds they were inextricably linked and indivisible. For some Japanese they still are.

A path to paradise in the lush moss garden of Saiho-ji

The item that prompted my thoughts concerns the World Heritage Site of Saiho-ji, a Zen temple more popularly known as Kokedera (Moss Temple). The temple was founded in the eighth century by a monk called Gyogi. By the fourteenth century it had fallen into disrepair and abandoned. This was a matter of concern to Fujiwara Chikahide, chief priest of nearby Matsuo Taisha. In 1338 he confined himself in prayer in the inner room of the temple, where he had a revelation that he should invite Muso Soseki, a monk at Rinsen-ji, to preside over Saiho-ji and lead its restoration. (Muso later became the founder of Tenryu-ji.)

Muso consented to the invitation and took up residence in Saiho-ji, and he constructed a garden based on two levels: a lower pond garden with path to stroll around, and an upper area with a dry landscape and place for meditation. Muso’s lower garden was apparently spread with sand; only in the nineteenth century, after flooding, did the moss grow for which the garden is now famous.

The collaboration of Fujiwara Chikahide and Muso Soseki shows just how tight were the ties of Shinto and Zen in those days. For us post-Meiji folk, it seems odd for two men of ‘different faiths’ to collaborate in such manner. But no doubt for the two men involved nothing could have been more natural, since the idea of ‘separate religions’ would have seemed quite absurd to them. [John Nelson, professor of Japanese Religion at San Francisco University, suggests that it might be equivalent to music, where what we would term as just music today might be divided tomorrow into quite distinct genres with their own peculiarities. Or to extend the analogy, perhaps it’s like thinking Country and Western is a genre, and then having the two parts split apart and the differences between them emphasised and enforced.]

Shinto shrine in the grounds of the Zen temple of Saiho-ji

A Zen rock garden – at Matsuo Taisha! (Created by famed designer, Shigemori Mirei)

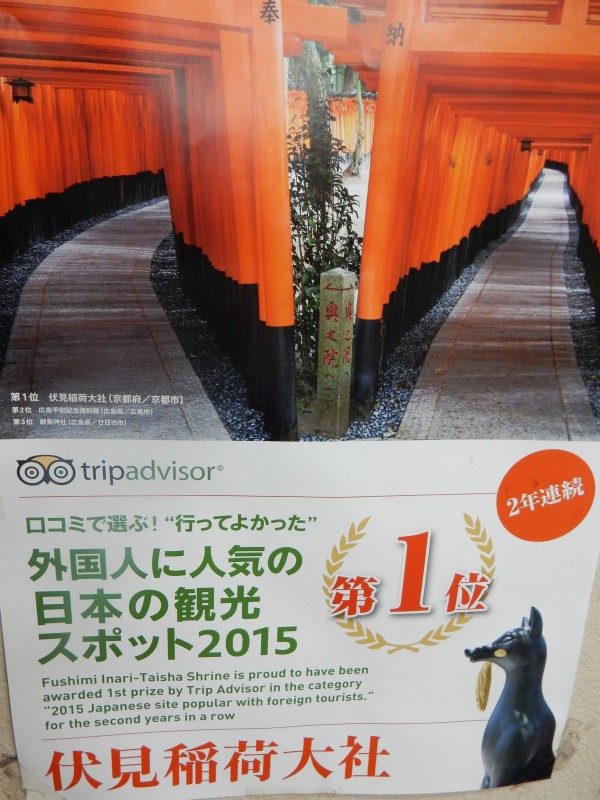

On Sunday I took an out of town visitor to a combination of Tofuku-ji Zen temple and the popular Fushimi Inari shrine. They are both in the south-east of Kyoto, a mere twenty minutes walk apart, and the Zen-Shinto combination makes a wonderful introduction to the world of Japanese religion. The large solemn buildings of Zen provide a contrast with the colourful bustling crowds at Fushimi, and yet the similarities are striking.

On Sunday I took an out of town visitor to a combination of Tofuku-ji Zen temple and the popular Fushimi Inari shrine. They are both in the south-east of Kyoto, a mere twenty minutes walk apart, and the Zen-Shinto combination makes a wonderful introduction to the world of Japanese religion. The large solemn buildings of Zen provide a contrast with the colourful bustling crowds at Fushimi, and yet the similarities are striking.

In this respect one has to wonder if Zen is not a more sophisticated view of the notion that humans are the children of kami. In other words, we all have ‘kami nature’ which is pure in spirit, just as in Zen we all have buddha-nature. It’s why we need the ‘magic cleansing’ of the oharai from time to time, to clean us of the dust of this world. No wonder that both Shinto and Buddhism use mirrors on their altars.

In this respect one has to wonder if Zen is not a more sophisticated view of the notion that humans are the children of kami. In other words, we all have ‘kami nature’ which is pure in spirit, just as in Zen we all have buddha-nature. It’s why we need the ‘magic cleansing’ of the oharai from time to time, to clean us of the dust of this world. No wonder that both Shinto and Buddhism use mirrors on their altars.

It’s the year of the monkey, which makes it a particularly apt time to visit the subtemple because of the celebrated fusuma-e painting by Hasegawa Tohoku that it houses (see below). It shows a monkey reaching out to grasp a reflection of the moon reflected in the pond below. It’s a telling Buddhist parable about chasing after illusion.

It’s the year of the monkey, which makes it a particularly apt time to visit the subtemple because of the celebrated fusuma-e painting by Hasegawa Tohoku that it houses (see below). It shows a monkey reaching out to grasp a reflection of the moon reflected in the pond below. It’s a telling Buddhist parable about chasing after illusion.