Yatagarasu, the three-legged emissary of Amaterasu

Today being 9/9, it’s the day of the Crow Sumo Festival at Kamigamo Jinja. (Green Shinto has carried a report on this unique event before; see here.)

Three has been a magic number with spiritual import since ancient times. It is the basic underpinning of the religious impulse through its birth-death-rebirth template, and the tripartite view of life is reflected in Siberian shamanism (and thereby Shinto) with its upper, middle and lower worlds. But if three has a potent significance, how much greater is that of three times three i.e. nine. You can see this in the Shinto wedding ceremony with its 3-3-9 ritual (san-san-kudo).

Shamanic pillar with crow on top

Nine had a magical import for Mongolian shamans, and it’s interesting therefore that the very shamanic Crow Festival in Kyoto should take place on this day. During the festival two priests hop and caw like crows in front of cones of sand representing the holy hill of Koyama where the Kamigamo kami first descended. This happened in prehistoric times when shamanism in Japan was still a living force, and one can presume that the kami descended into a human vessel, part man and part bird. In fact a secret ceremony to reenact this takes place every May which involves a cloak of feathers.

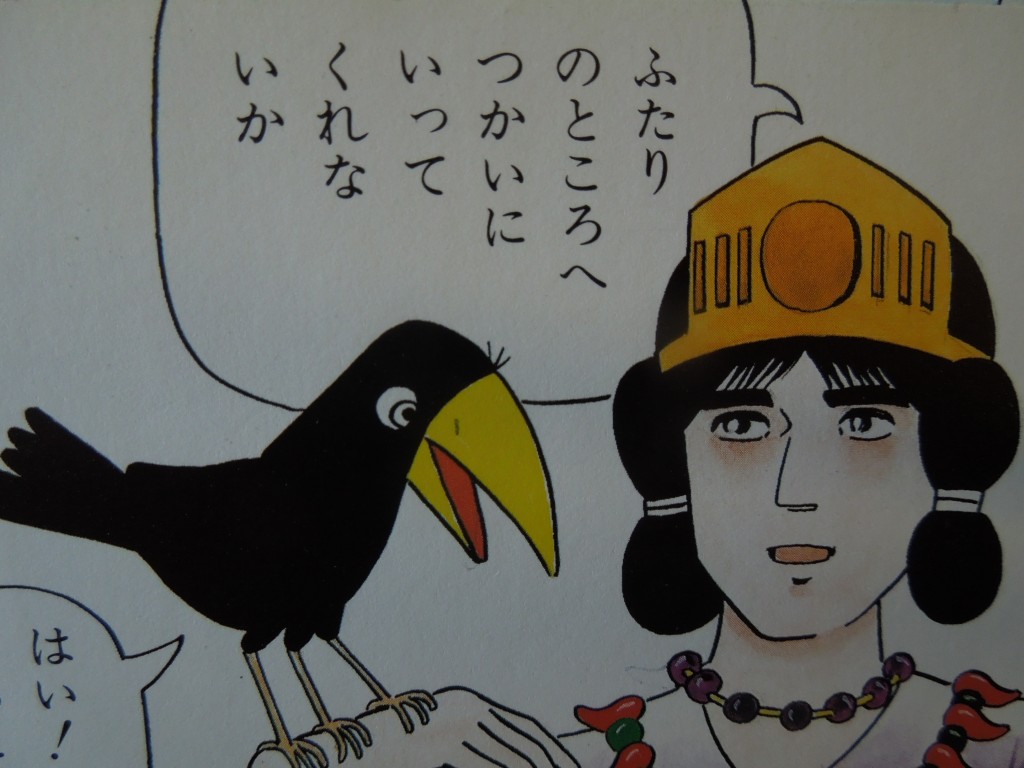

Now here’s the interesting thing. Kamigamo Jinja claims its founding kami was none other than yatagarasu, the three-legged crow of Kojiki mythology. Say what?! In the mythology the crow is a messenger of Amaterasu, sent by the sun goddess to guide her descendant across the dangerous Kii Hanto peninsula. For Kamigamo Jinja, that guide morphed into a member of the Kamo clan and ended up in Kyoto.

Crows and the sun are linked in many ancient myths, and might well derive from the black sunspots visible to the naked eye. A crow with three legs marks it out as being special, just as Siberian shamans are marked by a physical peculiarity to show their specialness. The emissary from Amaterasu might then well have been a shaman, or manifest through the medium of a shaman.

Tribes descended from crows makes one think of North American totems, where ancestral kin are depicted as ravens and the ilk. Indeed, the Crow Clan is a common feature of shamanic cultures, based on the shaman’s flight into the spirit world and an acknowledgement of the animal nature of humans – an instinctual understanding of evolution, you might say.

Emperor Jimmu seeks help from the three-legged crow

In this respect it’s interesting that in Siberia I once witnessed a crow dance by a shaman near Lake Baikal, and when travelling across Manchuria I came across a shamanic pole in the imperial palace at Shenyang from the top of which, explained a noticeboard, used to be hung a container with ‘grains and grounded meat to feed the divine bird (crow) in gratitude.‘

Food and gratitude are germane to Shinto. Indeed, its rites have been characterised as ‘spirit feasts’, when food is put out for hungry kami. One theory about the etymology of ‘kami‘ is that it is cognate with ‘kamu’, meaning to chew or eat, and in mythological and ritual practice, sharing food is a means of communion. It’s why in Shinto you share food after rituals with the divine spirit. And it’s why Christians symbolically eat the body and drink the blood of Jesus.

Crow-gods, crow totems, crows as emissaries of the divine. We tend to look nowadays on the black-feathered bird as a rather annoying or comical creature, simply an urban pest. But in times past those loud cawings were the voice of another world and those beady eyes portals into the divine. We’ve lost the art of connecting with them. We’ve lost the sense of magic.

On this day of days then, all hail the Crow!! Caw, caw, caw, hop, hop hop……

Feathered performer at a festival in Tohoku’s Shirakami, remnant of a shamanic past

************************************

For a detailed account of the festival, see John Nelson Enduring Identities p.104 and following.

The mask in the bottom image reminds me strongly of the raven masks carved by First Nations people in Canada. Both the styling and the colouring. Big black birds appear to have captured the imagination of many cultures. The association of the raven with death in some of them (including popular culture) wouldn’t help the image of black birds as a group. This may be one of the reasons we have lost the art of connecting with them. That’s a shame as they are remarkable creatures.

It seems we’ve lost the art of connecting with animals altogether, except as cute pets. Why do so many people choose to ignore the barbaric cruelty inflicted on animals in factory farming, or remain indifferent to the caging of wild animals kept in the cruellest conditions? Da Vinci was right; societies should be judged on the way they treat animals.

As an ecologist most of my friends and colleagues connect strongly with animals, particularly native ones. Many of them devote their lives to these animals to try and ensure their future survival. I admit that this is a small group of society and share your concern about the disconnection between most people and the way the animals they eat are treated. While there are some who are concerned about the humane treatment of the animals they eat, and others who don’t eat animal products at all, once again their numbers are relatively small. With more than half of the human population now living in cities, where interactions with animals are even more reduced, it will be critical to create opportunities for people to interact with and better understand the other animals we share the earth with. Working with children would be a good place to start.

Me again! Before seeing the reply to my earlier comment, and in turn responding to that, I’d returned to this post to share two more stories related to crows. The first is called ‘The Mischievous Crow’ which comes from a book of the myths and legends of Australian Aborigines published by W. Ramsey-Smith in 1930. The story relates to a crow hood-winking some pelicans to get some free food and the ramifications that followed. The second is called ‘Yawayawa and Crow’, a story from PNG retold by B Stokes and B Ker Wilson in the book ‘The Turtle and the Island’ (with wonderful illustrations by Tony Oliver), published in 1978. It tells the tale of how the crow came to be black, through the laziness of another bird. The crow has certainly captured the imagination of cultures around the world.

This is the last comment on crows from me, I promise. I felt it was important to share this information, which I’ve only just come across. For anyone interested in learning more about these mysterious birds, I’d highly recommend a 2010 documentary by PBS called ‘A Murder of Crows’. It has recently been posted on You Tube so is free to watch. The documentary demonstrates how remarkably intelligent crows are, drawing on research and experiences from across the globe (including Seattle and Tokyo). It’s a real eye opener. To access the documentary, just type ‘A Murder of Crows PBS You Tube’ into your favourite search engine and it should come up.

Thank you, Jann. The video is 52 minutes long, but quite fascinating. I’ve often observed how intelligent the birds are as they scavenge around the rubbish put out for collection here in Kyoto. They tend to be despised by modern humans, but you can easily see why they were revered in the past. Personally I’m a Crow Clan fan…