Emperor Naruhito at his ascension ceremony, receiving two of the three sacred regalia (the jewel and the sword)

Mainstream Shinto is based around the emperor system. In Japan, An Attempt at Interpretation (1904) Lafcadio Hearn wrote of its central role in unifying the nation, and from recent events surrounding the accession of Emperor Naruhito it is evident that the views Hearn put forward have hardly dated.

In 1956 Jinja Honcho (Association of Shrines) agreed on a kind of mission statement. It was put together for Shinto to have some equivalent to the Lord’s Prayer in Christianity, and it is recited before official ceremonies. Known as Keishin seikatsu no kōryō (General charactersistics of a life lived in reverence of the kami), it is described by the Kokugakuin encyclopedia as ‘a standardized doctrinal document’. It consists of the following main points:

1) To be grateful to the kami and ancestors, applying oneself to rituals with whole-hearted sincerity

2) To contribute to others through service without thought of self-promotion

3) To bind oneself in harmonious acknowledgement of the will of the emperor

The role of the emperor is thus of vital interest to anyone sympathetic to Shinto, and there has been debate in its leading circles about the significance of the emperor being a national ‘symbol’ as the Constitution of Japan puts it. Should the emperor be engaged in what might be seen as secular activities, or should he concentrate on his private role as semi-divine head priest?

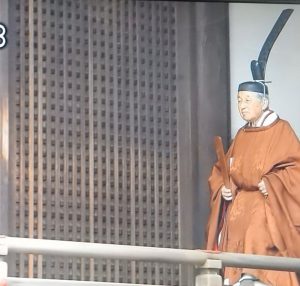

Emperor Akihito in priestly garb on his way to announce his abdication to the Sun Goddess

The following piece by John Breen dealing with these issues is extracted from a longer article on the subject entitled ‘Abdication, Succession and Japan’s Imperial Future: An Emperor’s Dilemma’. Please note that the paragraphing is mine, and that the original article for the Asia-Pacific Journal, updated May 5, 2019, is annotated, referenced and contains the Japanese kanji for names. (Click here should you wish to see it.)

What is interesting is the reaction of ultra-conservative groups, the self-appointed guardians of Japan’s imperial legacy. The most vociferous among them today is Nippon Kaigi (Japan Conference; hereafter NK). This is a powerful group, whose board features many Shinto religious leaders. The chief priests of the Ise Shrines, the Yasukuni Shrine, and the Meiji Shrine are among them. But NK matters because Prime Minister Shinzō Abe and the majority of his cabinet are members.

How did NK respond to the emperor’s address? NK was swift to deny press reports that it was “vigorously opposed” to abdication, but statements by key NK members suggested otherwise. The most articulate among them was Kobori Keiichirō emeritus professor of Tokyo University and incumbent NK Vice-Chairman… Kobori blamed the American makers of the “anti-kokutai Constitution” for creating confusion about the emperor’s role.

Other NK members were less measured. Murata Haruki authored an extraordinary opinion piece in the journal Seiron October 2017. His critique of Emperor Akihito makes for fascinating reading. Murata saw the emperor’s wish to abdicate as symptomatic of his failure to appreciate the unique nature of Japanese emperorship. The emperor cannot refer to himself as an individual, as he did in the broadcast, since he is semi-divine; he has no need for popular approval, since he is neither politician nor performer, but descendant of the Sun Goddess; and he has no business appearing on TV to address the people; it is his ancestors – the Sun Goddess and the first emperor Jinmu above all – whom he should be addressing.

Nippon Kaigi is, in fact, divided over the abdication issue, but it is clear that what matters to Kobori, Murata and their fellows is not the person of the reigning emperor, nor the Constitution, but the unbroken imperial line that began, so they believe, with the Sun Goddess. Emperor Akihito’s words and actions constituted a threat to their view of emperorship. Clearly, if an emperor can change the rules of succession on a whim, the myth becomes untenable.

What then would they and their allies have had the emperor do? On the specific issue of succession, they wanted him to hand the burdensome tasks over to a regent, and stay put. As a general principle, emperors should abstain from the sort of public service in which Emperor Akihito found meaning. They should instead remain within the walls of the palace, perform their acts “in matters of state,” and otherwise devote themselves to prayer.

The NK position… is that “symbol of the State” means precisely the emperor’s performance of prayer at the shrine-complex within the Tokyo palace. The complex in question, built in 1888, … comprises three sites. There is a central shrine for the Sun Goddess (the kashikodokoro) , which is flanked by the kōreiden, a shrine dedicated to the imperial ancestors (the spirits, that is, of all deceased emperors since the time of the mythical Emperor Jinmu), and by a shrine for the myriad gods of heaven and earth (the shinden). It is worth noting in passing that the rites which Akihito and his father before him performed at the shrine-complex since 1945 are precisely those of prewar Japan; they differ only in that they are private, and no longer public, events.

************

For more about Nippon Kaigi, please see here or here.

The new emperor has expressed his intention to follow in his father’s footsteps and steer towards a liberal interpretation of his role as ‘symbol of the State’.

Leave a Reply